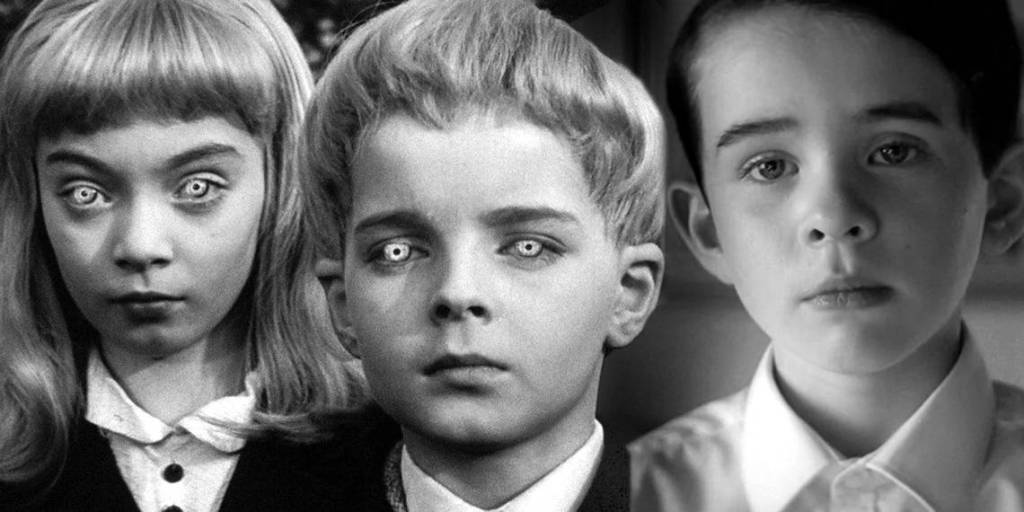

I first encountered the plot of John Wyndham’s post-World War 2 science fiction novel The Midwich Cuckoos by watching the 1995 film version. Directed by John Carpenter, the movie version was retitled as Village of the Damned and technically a remake of a the 1960 film of the same name. For the most part, I enjoyed the film, but I found the title perplexing. The source material is science fiction, a genre with which Carpenter is familiar, yet the world “damned” implies the village has been cursed. Therefore, I was surprised to find the bones of John Wyndham’s novel quite different.

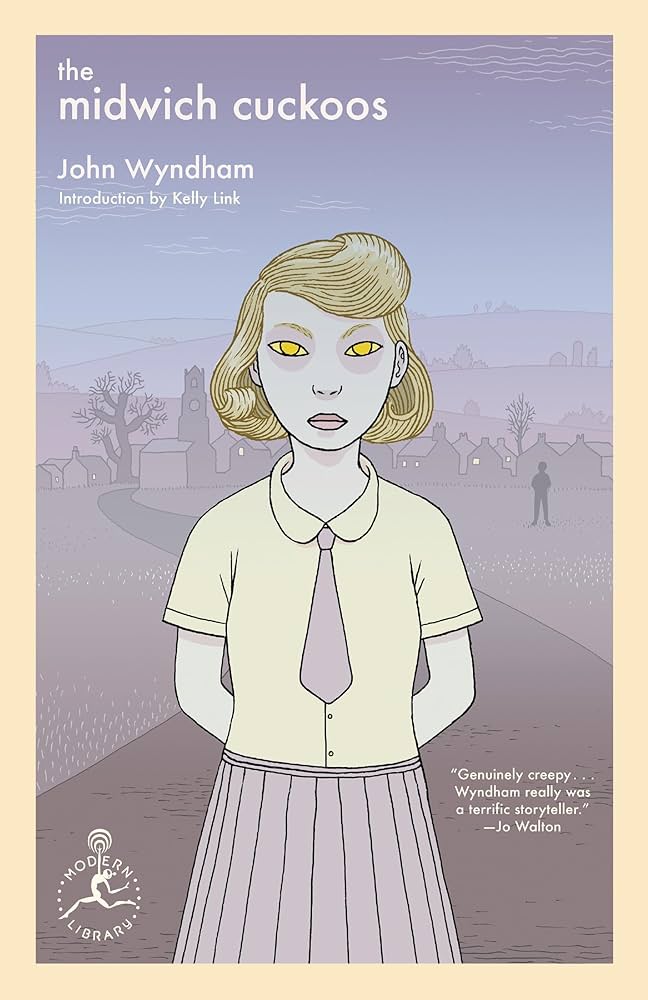

The Midwich Cuckoos was published in 1957. Wyndham is an Englishman, and when I discussed this novel with my book club, we couldn’t help but describe it as “so British.” The phrasing, some of which we did not recognize, the setting in a European context, and even the cold remove of the characters from emotions were some elements book clubbers pointed out.

The novel begins with every living thing, from humans to bugs, blacking out in a two-mile circle around the small village of Midwich. Our narrator, whose name I have forgotten, and his wife live in the village, but when the black out happened (or “dayout,” as everyone calls it because it happened during the day), they were out of town. Upon their return, they cannot enter the village from the two main roads leading in. Despite being warned by military personnel not to enter, the couple run through the hills and cross into the village, blacking out immediately.

The military are able to drag one person toward them after realizing there seems to be an invisible line that cannot be crossed without being affected. Once on the safe side, the individual awakens with no ill effects. The military use a canary in a cage to determine the invisible perimeter and start hooking people and dragging them to safety. Eventually, everything in Midwich awakens again. It’s not long after that every woman of childbearing age discovers she’s pregnant, whether she’s had sexual relations — ever — or not.

The novel progresses into a few key themes. Should Midwich inform the neighboring villages of what’s going on, or buckle down and support each other? Some women have committed suicide; others were beaten by husbands who assumed infidelity. It was all too close to home for an American like me where abortion rights have be stripped away and women are taking desperate measures. One main character, pregnant, argues:

“It’s all very well for a man. He doesn’t have to go through this sort of thing, and he knows he never will have to. How can he understand? He may mean as well as a saint, but he’s always on the outside.”

Indeed. All the Children (with a capital C, more like a class of species than youth) are born, about 50% boys to girls. They have golden eyes and other small physical differences, confirming for the resident philosopher, Zellaby, that these are not human children but put here via xenogenesis. After the births, parents notice they are coerced by the infants via telepathy. One parent that accidentally poked a baby with a diaper pin finds she is stabbing herself repeatedly on the arm with the pin. Another woman is forced to breastfeed in public, for which she feels shame. Still another tried to flee the village with her baby but is coerced into driving back to Midwich. The babies do not want to be separated. The whole uncomfortable feeling derives from lack of consent, giving this reader the icks.

The Children grow at twice the rate of human babies yet are susceptible to human issues. Three toddlers, and some adult villagers, die of the flu. Zellaby begins simple experiments to confirm his hypothesis that the Children have a hive mind. If he teaches a boy how to solve a puzzle, the other boys solve it without being shown how. Same for the girls, though the minds of the boy and girl Children are not shared. It seemed Wyndham may be suggesting that men and women think differently, a theme seen earlier when the women were pregnant and the men unattached to the infants.

Nine years pass, and the Children look like teenagers. They have all left home and moved into a house on a grange where Zellaby and other teachers educate them. The Children’s intelligence increases exponentially because only one Child needs taught a lesson, so multiple lessons commence simultaneously. Eventually, one Child is accidentally struck by a car, so they coerce the driver into crashing his vehicle, killing himself. This defining moment is a catalyst that forces Midwich residents to ask if they should make their situation public, if they should leave the village, or if they should fear the Children.

The novel reads much like a thought experiment, a vehicle in which readers can ask, What if they were not the dominant species? What if another species came to replace them? Would human casualty prevent humans from saving themselves if they could destroy the Children, too? The Midwich Cuckoos is definitely a thinking-person’s novel.

Other than Zellaby, I couldn’t remember the characters, their names or features or occupations, and it didn’t matter. Someone talked and pushed the experiment forward. Furthermore, I wasn’t sure why the narrator was a man instead of omniscient, which would have been clearer. Neither of these facts matter; it’s a good science fiction story, one that covers heady topics. At the end of book club, the leader asked if any of us would have voted to kill the Children. Several people said they would “gas” the Children in their house on the grange. I had to point out the weightiness of wanting to “gas” a group unlike yourself in a post-WW2 novel.

The overall Britishness of the novel, which you find so unfamiliar, is the writing I grew up with – an upper middle class University-educated man (with subsidiary wife) is put in an unfamiliar situation and deals with it, with a mixture of muddling through and deduction.

I like your thought about the boys hive-mind and the girls hive-mind indicating that males and females think and do things differently.

I agree with you about names, but did you notice that it was the narrator’s wife and maybe the vicar’s wife who came up with all the practical solutions for dealing with their neighbours’ pregnancies (I was especially pleased that the author chose not to make anyone below the age of 16 or so pregnant).

LikeLike

I did notice that it was a few wives coming up with solutions! At one point there was a comment about the men just tolerating the experience whereas women basically circled the wagons. Women had to come up with a plan to convince men not to beat their wives for fear of infidelity.

LikeLike

Wait, they waited until these “children” were teens until they thought of fearing them???

I’ve been spending 6 days a week with my 10-week-old grandson and I find that it’s hard NOT to think of some of the ways an infant acts as uncanny.

LikeLike

I think all the wild incidents were kept on the downlow because the village is so buttoned up, failing to communicate what is happening in each home. Instead of a giant program, it’s just little things here and there, or so they think.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve not read this one but I have read Wyndham’s Day of the Triffids with its walking carnivorous plants, that may or may not have been created by the Soviets, taking over the world. Interestingly, the book doesn’t end with humanity defeating the Triffids but with a battle between human factions–militaristic authoritarians v more egalitarian.

LikeLike

I had previously heard of Day of the Triffids and am interested in reading it, probably aloud to Nick so we can chew it over together. When people say WW2 affected the fiction that came thereafter, I see it clearly in Wyndham’s work, whereas in some American post-WW2 fiction I’ve read, it seems that there are just a lot of soldiers getting drunk and cheating on their best girls at home, which is not what I want to read because it doesn’t say much (to me) about what happened.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Triffids is quite sexist, but you will likely find the story interesting since it captures so many of the post WW2 fears and thinking. I did like that it had no grand concluding battle with the humans defeating the Triffids and everything being ok.

LikeLiked by 1 person

John Wyndham is a genius! I read all his books when I was a teenager. We studied Day of the Triffids at school and I enjoyed it so much I borrowed all his others from the library. As an adult, I read The Crysalids, which I reviewed on the blog, and it still stands up. He was very much interested in how we ‘other’ people and treat/condemn them, and I suspect that’s the product of living through WW2 and finding out what happened during the Holocaust.

LikeLike

You comment just made me question whether this book is about the Holocaust. The Children are trying to thrive, but nations keep wiping them out completely–a Holocaust of sorts. Do you think that’s something Wyndham is saying?

LikeLike

No idea, but plausible. It’s more than 40 years since I’ve tread that book!

LikeLike

Read, not tread. 🤣 Also, I think the book probably says more about Cold War fears (of infiltration, Communism etc) than WW2.

LikeLike

Interesting….thanks for your perspective as a super fan!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I enjoyed this one when I read it, although not as much as some of his other work! I think Day of the Triffids is the one that’s endured the most for a reason. It sounds like it made for a great book club book – there’s lots to discuss, especially about Zellaby’s choices.

LikeLike

One of the first things we did in book club was match some challenging vocab words to their definitions, like a little quiz for book nerds! Most folks didn’t know the meanings, and I was in the same boat (though having the definitions made it easy to match because a root word, etc. would steer me in the right direction). I think I’m going to give the Triffids book a try and read it aloud to Nick. I hope you are well! I’ve missed reading your blog posts and think of you often.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m okay! We’ve had an absolutely beautiful spring, so on the rare occasions that I haven’t been working I’ve been outside enjoying the sunshine and flowers. Hope you are well too! Are you coming to the end of your internship? Still up for reading Tale of Two Cities together in May?

LikeLike

I just got home from my internship site on Saturday and am very discombobulated. Last night I woke up and didn’t know where I was. I didn’t realize that could happen. I think I would still be good for reading A Tale of Two Cities in May. Do you have an idea of when you’d like to get together for a video chat? Preferably the end of the month would work for me.

LikeLike

Yes, end of the month would work for me too as my module will have finished running by then. I’ll email you with some potential dates when I get home!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m sure I read this years ago but what strikes me now in reading your review is, as you point out, the horror of pregnancy being forced upon all these women. I like what I’ve read from Wyndham because the premises he comes up with are chilling and kind of out there but more in a psychological way than a blood and guts kind of horror.

LikeLike

True! Horror is such a spectrum, which is why I tend to define the genre as “anything designed to be horrifying.” Some of the nonfiction people read is horrifying to me, and I think the authors intend it that way — to shock and awe audiences by giving them horrifying facts that we’re drawn to like a moth to a flame.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A lot of true crime seems pretty horrifying to me – more so because it’s true! There can definitely be an element there if authors drawing in readers by trying to shock them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Whoa this sounds like a meaty book club discussion!!! Especially the ‘gassing’ comment – yikes! How did everyone respond when you brought up how problematic gassing people is???

LikeLike

Girl, it got REAL quiet.

LikeLiked by 2 people

LOLOLOL

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is one of the very few science fiction novels I’ve read and though it’s decades since I read it and thus have forgotten the details, I remember how engrossing I found it. Your discussion about the deeper meaning has me thinking I should re-read it because I missed all of that – just thought it was a darn good story

LikeLike

Thanks, Karen. Interestingly, I don’t even think of this as a science fiction novel because there is so little science going on. The narrator, oddly, is not a scientist, or at least not in a way that’s pronounced if he is. It’s possible I’m just forgetting, but most of the characters were forgettable except for a few of the women. It doesn’t bother me that there isn’t very much science, though, because I do think of this as a social commentary book.

LikeLike

I’ve planned to read this book for a while. In fact, last year I bought a second-hand copy, until I realized that it was a (very) abridged version for class study (middle school? high school? I shall never know). Your post made me even more eager to read it.

LikeLike

It’s a short book, but it can feel like a slow read due to the language. I also think the choice of narrator can slow down the reading a bit, too, but that doesn’t make it any less interesting. I hope you get to it soon.

LikeLike