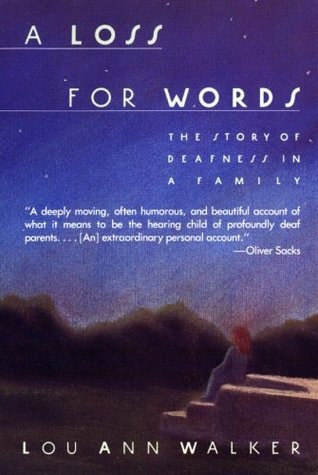

In the resources folder of the American Sign Language course my spouse and I are taking, several books are recommended, including the memoir A Loss for Words: The Story of Deafness in a Family by Lou Ann Walker. I found Walker’s story to be incredibly engaging and emotional, bringing me to tears of joy and laughter many times. And yet, a young adult, Walker tells new boyfriends her parents are deaf with a sense of shame, announcing their situation apologetically, or even delaying telling her new partner. Her feelings, to me, are a reflection of the time period. Walker was born in the 1950s, and the memoir was published in 1986. Perceptions of disability and D/deaf people have changed.

Walker’s parents were born in the late 1920s in Indiana. Both became profoundly deaf before the age of two, and because they were born during a time when speaking was an indication of intelligence, both were sent to the Indiana State School for the Deaf where the curriculum emphasized oral skills and lipreading. Walker notes that the school did not teach American Sign Language (ASL), but it was used. Deaf children struggled with the sames lessons year after year because around only 25% of people can truly lip read, and feeling a speaking person’s throat while they talk in order to feel their vocal cords doesn’t do much in the way of learning to talk.

A Loss for Words is a personal story, but it educates as well. Walker’s grandparents on both sides felt shame that they had deaf children, as if blame would fall on their families. The grandparents never learned ASL, erecting an unfortunate wall between them and their children. Although people thought deafness meant low intelligence, Walker’s parents didn’t pay attention to what their parents told them about their limitations:

[My mom’s] parents wanted her to move back with them; she knew nothing about writing checks, looking for apartments, getting utilities hooked up, but there weren’t any jobs for her in Fillmore, no deaf people, not much to do. She decided to strike out on her own. Soon she was living in an Indianapolis apartment with a deaf girlfriend who’d been a classmate. Mom was working as a keypunch operator for a company that made construction equipment.

Much like any high school graduate, Walker’s mother has a lot to learn and friends with whom she can start her independent life. I felt that whenever Walker attempted to show how things could be challenging for a deaf person, I mentally countered with the challenges faced by most people of the same age.

A big part of A Loss for Words is Walker puzzling out her relationship to her parents, deafness, and society. Walker acknowledges that most children of deaf parents feel guilty. Perhaps they have not been good children, or didn’t do enough to help their parents, or didn’t support deaf people enough, or didn’t work hard enough to change societal perceptions of deaf people. Despite having a full-time job, Walker spends much of her free time interpreting in prisons, court rooms, psychological evaluations, and colleges. She also spends time with a deaf street gang to write a piece on them for a magazine. Her time is torn in so many directions that she begins to break down:

I had been the medium for such insane words a thousand times in my life. And before that I had been the patient explainer to my parents and for my parents. I had explained and recounted and been the voice. A robot of words and sounds. And suddenly I wanted to scream. For the first time in my life, I wanted to cry out. This isn’t me. It’s [the person for whom Walker is interpreting]! I have talked and listened and heard and there is no me!

Through her sessions interpreting from ASL to English, Walker emphasizes that they are two different languages. Many people think ASL is a direct translation from English; however, again educating her readers, Walker explains that the grammar and syntax of ASL is different from English, and that “A conservative survey once showed that the average deaf high school graduate has a third-grade reading ability. Writing is more difficult to judge.” Frequently, Walker is asked to correct her parents’ writing to make it sound less like a non-native English speaker. However, Walker’s mother “didn’t just want to copy it over; she wanted to learn from the exercise.”

While I thought A Loss for Words might be a memoir about the heavy responsibility of being a hearing child of deaf parents, Walker never makes her parents sound helpless or like they’re using their children. When her parents want to make a phone call, they always sign, ” ‘Please, would you mind to…?’ and they’d make the request.” Or, when Walker swears she hears a man talking to himself outside her bedroom window night after night when she’s just a little girl, she runs to wake her father:

He’d search the whole yard, then walk to the end of the driveway, flashing the small beam up and down the street. He never once refused to go out, nor did he ever tell me I was making it up, but after I’d awakened him several times that third summer, I decided it must all be in my head.

I’ve never read another memoir in which the parents are so unfailingly kind, modeling the kind of behavior we wish to see in society. Walker recounts zero examples of her parents hitting her (and this was the 50s!) or signing cruel remarks after she or her sisters have behaved badly. If anything, they are understanding to a fault.

After Walker moves away from Indiana to the east coast for college, she’s separated from her parents. When she calls, her younger sisters interpret what Walker says on the phone to the parents and then says what they sign back. One call in particular had me in tears:

“Looahn.” It was Mom’s breathy voice. Kay had put the receiver to her mouth. Then I heard more shuffling. Mom had backed away as if scared, then looked questioningly at Kay. “Can she hear me?” Mom signed to Kay.

“Yes,” Kay urged her. “Go on.”

“Looahn,” Mom said again. “I lahv you.” She paused to breathe. “I mees you.”

Then Dad. I could hear his preparatory swallow.

“My sweet daughter. I lahv you. Your Daddee,” he said.

It wasn’t even how sweet and tentative the parents were on the phone that got to me, it’s that they are always like this with their children.

And of course parents are funny, and Walker’s are no different. For a time, Walker attempts piano and fails. Then, she tries violin and is terrible. Likely because her parents can’t hear music, Walker doesn’t want to invite them to an upcoming orchestra concert, but the band leader insists parents be there. Unfortunately, while she’s playing in the concert, Walker can see her father has fallen asleep. His head is drooping on his chest, which is such a dad thing to do. But, what if he starts snoring and her mom can’t hear to wake him?? Oh, the humiliation! This is one of those examples in which I felt both hearing and deaf fathers would be embarrassing to a middle school child if they fell asleep. In an effort to praise her daughter, Walker’s mother signs, “I liked watching all the bows go back and forth together.”

A Loss for Words was a wonderful memoir that I couldn’t put down, capturing Lou Ann Walker’s parents’ personalities, their home life, and society’s reactions to people with hearing loss.

It does sound like an important memoir, but I wonder if her parents are so perfect because they are/were still alive and she didn’t wish to hurt them.

Interestingly, during Covid when our state leaders are giving updates every day the signers beside them are becoming stars too.

LikeLike

They were alive when her memoir came out, and they read it before it was published. If I remember correctly, they were slightly confused, or some emotion like that, but wanted her to publish the book if it helped others. I would imagine they didn’t understand why Walker didn’t feel like she had her own voice when they were so careful to not abuse her ability to translate. Honestly, the sound like innocent, hard-working, proud people, and I always felt like she captured them fairly. I was looking for meanness or sympathy, but Walker doesn’t go either direction.

Yes! The signers are everywhere now due to the pandemic. They seemed rare before, but now you always see the same one behind this or that governor.

LikeLike

This sounds lovely and it sounds nice to read a memoir where the parents are actually caring! I didn’t know until recently that ASL was it’s own language. I always assumed it was a literal translation. With the regular news updates during the pandemic it’s been interesting to watch the ASL translators. Sometimes it’s easy to see what they’re saying (like the word vaccine) and you can tell how much facial expression is a part of the language.

LikeLike

It’s hard to remember what to do with your face. Sometimes the face conveys emotion, sometimes it conveys what would be vocal inflection, and much of the time it is punctuation. I believe in Canada you guys use ASL, but the French folks in Quebec use LSQ (Langue des signes québécoise).

There are some people who do SEE (signing English equivalent), but the Deaf community see that as hearing people changing their language, which is part of their culture. ASL has no “to be” verb, no plurals, and no articles, for instance.

I really thought this was one of the balanced memoirs I’ve read in ages, but it also sticks to the reality of how the author felt, too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, it’s my understanding that in Canada we use ASL. I didn’t know about SEE but I can understand how that would be something different, especially once you understand ASL as its own unique language.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This sounds delightful! One of my favourite films when I was a teenager was about being the hearing child of deaf parents, Jenseits der Stille (both sides of the silence). We watched it originally in German class but I ended up loving it for its own merits. If memory serves, the girl in it becomes a musician, and it’s about them all navigating the effect that it has on their relationship. Though I haven’t watched it in many years so may be misremembering.

LikeLike

Lou, a couple of years ago I saw a French movie where a girl with deaf parents becomes a singer. I loved it. But a search brings up this withering criticism

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/dec/19/la-familie-belier-insult-deaf-community

LikeLike

Bill, I can see what the author is saying here, and while I haven’t seen the film, I also wonder if the issue is less “why can’t my parents hear me?” and possibly more “is it betraying my family to enjoy music they don’t care about?” I may be completely wrong, but just a thought. I know the remake, CODA, has deaf actress Marlee Matlin as the mother. I read that they wanted her because she’s won an Oscar and is wonderful, but they wanted hearing actors to play the other two deaf characters. Matlin said she’d drop out if that happened, so there are three deaf people in the CODA (2021) film. I will say that the 2021 film is described on Wikipedia as the hearing teen having to “…decide between helping her family and pursuing her goal.” Uh…..do they need help because they’re deaf? I can see how that would make Deaf people upset, as if they are incapable.

LikeLike

We have the same problem here and I’m sure you do too – migrants relying on their children to translate. I’m sure the great majority of those adults are pleased when their children merge into the wider world.

But it is always chastening and informative to read POVs which contradict one’s easy assumptions.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I can see what the author is saying, though in Jenseits der Stille the lead characters are played by deaf actors, and I saw a couple of reviews from children of deaf parents saying that they really appreciated the film and found that it captured some of the nuances of their experience. Like Melanie says, the film (at least per my memory) focuses more on her feeling guilty for loving a world that she feels her parents don’t have access to, not so much being frustrated that they can’t hear her.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah ha! That is the name of the movie my mom was trying to think of but could not! We were both searching Google while doing a video chat and could not find it. They remade this film, and the new version, simply called CODA, comes out later in 2021. The girl sings, if I remember correctly.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow. They sound like incredible parents. When people cry about wanting to go back to the good ‘ol days, I think of situations like this. Where people were treated badly because of some difference, and I don’t know why anyone would want to go back to a time of people making other people feel bad about themselves. (Obviously, this still happens today but I feel like we’ve made progress.)

LikeLike

I had this nagging feeling that these parents knew what to do intuitively. If I think about the time period, I don’t recall loads of books on parenting, or parenting classes. There was great combo of “you don’t ‘own’ you children” and “let them be independent and make mistakes.” An excellent story of kindness is when the mother got new plates advertised as indestructible. The author, just a girl, decided to show off the new plates to her friends, eventually shattering one. She trod up the steps and confessed her misdeed, to which the mother replied, “Yes, I watched you” and gave her a hug.

LikeLiked by 1 person

To be fair, the company lied! lol. That would have been my go-to excuse. 😛

LikeLiked by 1 person

Aw this does sound like a really sweet book. A love letter to kind parents-this book is so rare these days! haha most of us are just complaining about our parents (many with good reason) so this seems like a nice change of pace. And thank god society is becoming more accepting of and accommodating towards deaf people! I think signing ASL is so cool, I’d love to learn. How are you finding it? Difficult?

LikeLike

I’m taking to ASL like a fish to water. It’s so efficient and makes sense, and I am AMAZED that I don’t have to hear. For me, hearing is work. Constant work. It’s comparable to the focus you might need to shelve library books in order, or work on a project involving copying and pasting data — something like that. Where you’re using your concentration on a lower level, but all the time?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hmm yup I totally get that. I’m so glad you are enjoying it, what an amazing skill to pick up!

LikeLiked by 1 person

That sounds like a great book and an excellent insight into that particular kind of family. And how lovely to read about kind parents, to be honest (to be fair, that book I just read about Canadian Muslims, the parents are lovely).

LikeLike

It’s uncommon to read about nice and normal parents. I always get the horrible monster parents or the “reach for the stars because you’re dreams are the best!” parents, and I don’t really enjoy either.

LikeLiked by 1 person