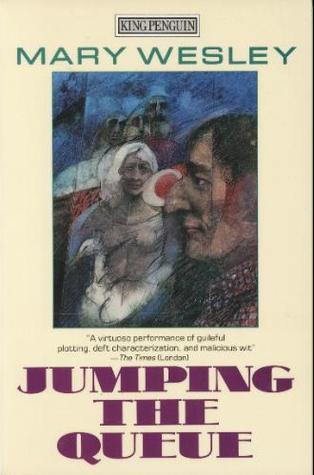

I had never heard of Mary Wesley until I picked up Jumping the Queue in a used bookstore. The back of the book says something about two people who are going to commit suicide somehow saving each other, and I guess that appealed to me. I learned Wesley began publishing at age 71, and Jumping the Queue was her first adult novel, so from there on on out, I was rooting for the author and her book. I wish I hadn’t.

The basic plot is Matilda is feeling very, ridiculously old, and so she’s going to kill herself before physical deterioration sets in. Who wants to be old, immobile, have cognitive issues, etc.?? So, she plans a picnic, sells off her beloved pet goose, and heads to the English seaside, where, when the tide is perfect, she can drink a bunch of pills and be swept off in the tide where her corpse will surely ruin someone’s day. However, everything gets thrown off because some family has the audacity to enjoy the beach at the same time, and so Matilda’s plans are foiled.

That day, she finds a man who is also about to commit suicide, except he’s going to jump off of something (a bridge, if I remember correctly). This is Hugh, better known as The Matricide, because the dude is a murderer. And, you know, killed his mother. Matilda finds it in her heart to pretend they’re in love, thus evading police, and they end up back at her villa in the woods where — hooray! — the pet goose has made his way back home after murdering all his barn-mates at his new home. They also pick up a stray dog them name Folly, and the animals are the best part of Jumping the Queue.

From there, the book just gets weird in ways that were not appealing. Matilda’s dead husband may have been gay, a spy, sleeping with their daughter, you name it. Matilda heads to London to stay with an old friend, and all she does is shop with checks she expects will bounce, eat with her annoying old friends, and fetch Hugh’s shoes from his apartment, which is being watched by police. Where was the book going??

Eventually, we learn that Matilda is in her 50’s, which ruined most of the crisis she seemed to be having. Since when do women who turn 50 look in the mirror and say, “Yes, I might as well be dead now, for I am so old.” Maybe it’s because her children don’t visit, but the narrator emphasizes Matilda is not maternal in the least, so was she even a decent mother?

We are meant to believe that Hugh is in love with Matilda, except it’s revealed in a letter and not in, you know the build up of their interactions. I guess if I can fall in love with a toad in my garage simply because it exists and deigned to live inside my property, Hugh can fall in love with Matilda.

Overall, though I do NOT recommend this book for one specific reason: it has the most gut-wrenching, unearned ending I think I’ve read . . . maybe ever. I had to stop reading, in fact. I considered not finishing the novel with only a short chapter or two to go. But, according to Wikipedia, Mary Wesley was “…one of Britain’s most successful novelists, selling three million copies of her books, including ten bestsellers in the last twenty years of her life.” I’m going to have to take their word for it, because I won’t read her again.

She’s one of those writers I have it in my head to read, but I’ve not read it yet. Have you seen her Wikipedia page and what her mother said about aging and dying? Albeit was after her father had a drawn out death apparently. My point though is that someone born in 1912 could very well have had a different attitude to what 50 years old is, particularly for women who were seen as past their use-by date, compared to what we think now? (That said, my grandmother who was born in 1902 and died in 1982 had a zest for life that I never saw fade. She died very quickly of heart disease, and at 50 was well engaged in life.)

Anyhow, you have made me think, but I think I’ll still keep her on my list, just not high priority.

LikeLike

I was going to make the same point about attitudes to age. After all, so many jobs, including being a housewife, used to be much more physically demanding. I know that it transformed my nan’s life when she got a washing machine, which I think would have been when she was in her mid-30s – so that she no longer had to spend a full day every week using a mangle. The introduction of labour saving devices (and an indoor loo!) made such a difference that my aunt talked about it in the eulogy she gave at Nanny’s funeral. I think my nan’s parents, who were farm labourers, died in their early 60s – so I can see how a 50 year old who had been doing hard physical labour might feel older than most 50 year olds would now.

LikeLike

Thanks loulou for elaborating … one of the most memorable books l’ve read is one called Spaces in her day based on women’s diaries from around 1920s and thereabouts. The chapter on washing was so vivid. And it just reinforced my feeling that the device I would give up last would be the washing machine.

LikeLike

I lived in a flat without a washing machine for two years (no plumbing for it) – I did have a laundrette about twenty minutes away on the bus, so sometimes I used that and sometimes I hand washed my stuff. Two years was more than enough to do me for a lifetime!

LikeLike

I bet … !

LikeLiked by 2 people

Whew, especially if you have to carry your things on a bus.

LikeLike

Oh, wonderful! I had just left a comment for Lou saying her family’s stories are ones I wish to read instead of Jumping the Queue. The novel Spaces in Her Day is available at a couple of local university libraries.

LikeLike

Ah no, it’s not the novel – I think there is one with that title – but a history, by the Australian Katie Holmes. Is that the one you’ve seen? It could be in university libraries.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wish there were more about the main character’s life in the novel to help me see what you and Sue are describing. From the sounds of it, she wasn’t even a person before, her backstory is so weak. She wasn’t a motherly mother, so she doesn’t miss her children. Plus, the original suicide plan included her AND her husband, because I first thought she was depressed from being widowed. The lives you’re describing, Lou, are the ones I want to read about.

LikeLike

Hmm, I hadn’t thought about what it meant to be 50 several decades ago. I believe the novel is set in the 1960s, so once the main character’s children are all out of the house, maybe she feels useless. On the other hand, she says she was never a motherly mother, so you’d think she experience a sense of freedom.

LikeLike

All good points Melanie. I think we were also thinking physically. Women I think tended to feel and dress older then – because they had worked hard, because it was expected of them, and so on. When you are given to understand 50 is old by society you feel it I think. Boomers are bolshier about things like this!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve been listening to my own mother complain about being old since she turned 30. She’s currently 75 and still complaining.

So, did Hugh kill Matilda? Or maybe she killed him? Or murder-suicide? Or maybe the goose took them both out?

LikeLike

Wow, that’s a long time for one person to complain. Has she considered trying ziplining?

Neither of them killed the other, and the goose was killed by another animal.

LikeLike

Absolutely not, she’s too old! Seriously though, she has spinal stenosis at this point and uses a walker to get around so she has reached a state of self-fulfilling prophecy.

LikeLike

My first and only thought was, “That sucks.” Which isn’t terribly eloquent.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Woof! This sounds weird and not in a good way.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is like the opposite of our previous conversation about boomers insisting they’re not old! It seems extra weird that this is a book written by a woman in her 70s. I once thought 40 was pretty old but that was when I was 10. Your line about loving the toad genuinely made me laugh out loud!

LikeLike

You know, that’s a great point. The author had been through 50 and 60 and 70 — so why was her perspective of an unmotherly mother so distraught? Wouldn’t she be happy her kids were gone so she could get on with the business of living? It’s a mystery.

Re: the toad comment — I wrote a couple of reviews in one afternoon when I guess I was feeling a bit feisty! People keep commenting on my humor 😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] to my review of Jumping the Queue by Mary Wesley: in general, I now see that I had not considered how 50 might be a different type of […]

LikeLike

Wow, that is… a wild ride… Maybe this one wasn’t one of her bestsellers? Hard to imagine this being widely appealing. Love that she saw such success after starting her writing career at 71 though, that’s inspirational!

LikeLike

Because she was 71 when she started writing adult novels, I would assume she had a better sense of what a 50-something woman’s life was like in the 1960’s. It felt like a man wrote Jumping the Queue and got just about everything wrong.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah yeah, that makes sense! Hard to blame writers for the era they lived in, but it is so sad to see how thoroughly some aspects get internalized.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Okay, I laughed about the part where she wanted her body to wash up on shore and ruin someone’s day. That’s my take away from this book that I shall not read. 😛

LikeLike

It’s definitely the crotchety way to conceive of one’s death, but now that you’ve phrased it how you did, it seems pretty funny.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s very dark humor and that’s my favorite.

LikeLiked by 1 person