About mini reviews:

Maybe you’re not an audio book person, or maybe you are. I provide mini reviews of audio books and give a recommendation on the format. Was this book improved by a voice actor? Would a physical copy have been better? Perhaps they complement each other? Read on. . .

CONTENT WARNING: domestic abuse and murder

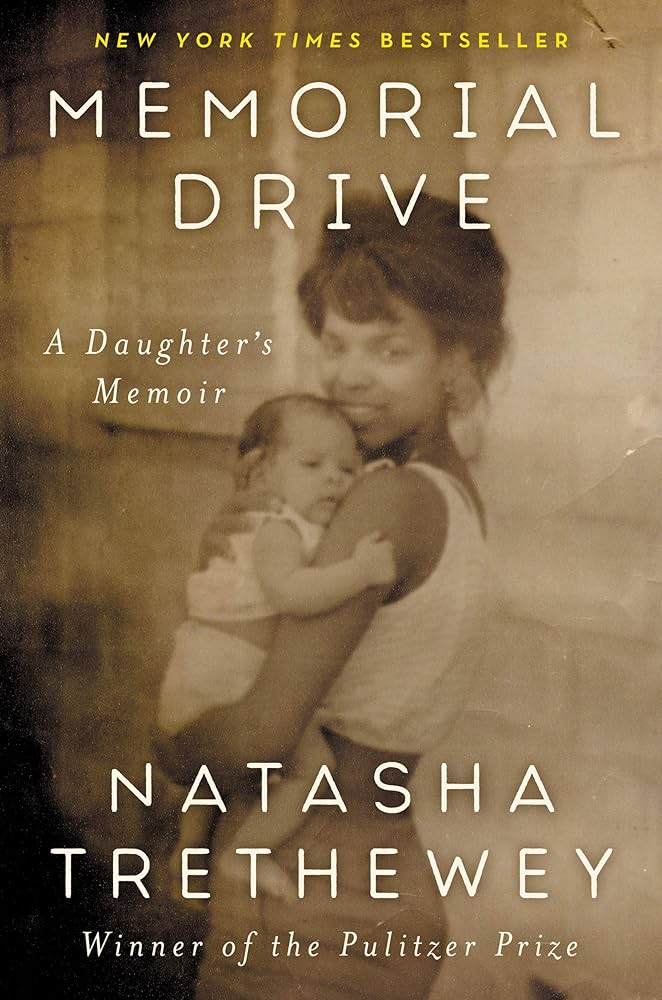

A relatively short memoir (4 CDs), Memorial Drive is written and read by Natasha Trethewey. In it, she briefly recounts the relationship between her parents, a Black woman named Gwendolyn and white professor named Eric, in the 1960s in Mississippi. They had to travel to Ohio to get married because interracial marriage was still illegal in the south. I barely noticed when Trethewey’s father disappeared from the story. Then again, when parents divorced in the early 70s, kids often went with the mom. No, the focus is actually on Gwendolyn’s relationship with Trethewey’s step-father, Joel.

Joel seems to randomly appear on the scene when Gwendolyn comes to pick up the author after a summer of staying with her grandmother. You have a new brother, Gwendolyn says, and I’ve married Joel. Joel begins terrorizing Trethewey, threatening to send her to an asylum for “crazy” people, making her pack her bags while Gwendolyn is at work. He drives her around for hours while she sobs in the back. Eventually, the memoir leads to Gwendolyn surviving domestic violence and kidnapping, getting a divorce in 1984, and starting a career in social work after earning her master’s degree. Joel spends a year in jail. Tragically, in 1985 when Trethewey was nineteen and in college, Joel was released from jail and made good on his threats to murder Gwendolyn using a gun.

There is a lot of missing communication in Trethewey’s first experience with the loss of her mother in 1985. Firstly, Trethewey didn’t realize her baby brother was her half-sibling. She assumed her brother was Joel’s son from another relationship. Other missed communication? It wasn’t until something like twenty-five years after the murder that she received information from the police, including transcripts of phone calls the police department traced between Gwendolyn and Joel.

The author reads the transcripts– and it goes on and on, so here I say proceed with caution. I started to feel sick listening to the way Joel could justify his lethal threats, using excuses such as his time in the military in Vietnam, that Gwendolyn “took everything” from him, that it’s more important to kill her than worry if Trethewey and her brother were murdered in the process, etc. In contrast, I heard Gwendolyn saying calming responses, never promising anything, while trying to be honest without angering Joel. It’s infuriating, because of course I picture myself telling Joel where to stick it because she had a good job and a place to live. But he knew where she worked and lived, and he was following the author, Trethewey, around with a gun when she was in high school.

The result of not having all the information in 1985? Trethewey discovers exactly what happened to her mother via the police after spending decades trying to heal a deep wound, and now she’s experiencing it all over again because she reads police reports of what the neighbors heard — screams, pleas, two gun shots. The worst part was Trethewey learning that the police knew Joel threatened to kill her mother, that he had spent a year in jail for physically abusing and kidnapping her mother, and that he knew where her mother lived. They could have prevented Gwendolyn’s death, but did not. Memorial Drive was published in 2020.Joel was released from prison in 2019, thirty-four years after the murder.

Lastly, I will add that I recommend this book in text form, not audio. On two occasions, I mistook Gwendolyn’s personal journals for Trethewey’s own experiences, thus causing some confusion.

For more information about why domestic abuse is handled poorly by police departments, please read my review of No Visible Bruises by Rachel Louise Snyder.

Oh wow, this sounds intense. I like Trethewey’s poetry very much and when this book came out I thought I’d read it, but haven’t gotten around to it. Now I’m not certain I will.

LikeLike

I found it extremely hard to listen to Trethewey’s story about domestic violence and read the Old Testament at the same time because what the Lord says to the people sounds exactly like the transcripts between the author’s mother and her ex-husband.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Domestic Abuse (OR Domestic Violence OR Family Violence) is a big issue in Australia and is receiving a lot of media and political attention. There have been many horrifying stories even just this year. Three or four years ago I read a Stella award-winning analysis See what you made me do. The research Jess Hill did has been taken seriously by various professionals – legal, policy-makers, counsellors and more. It was tough to read but so good, so thorough.

Trewethy’s story is horrifying. I can’t imagine what her mother endured and what she herself endured and has had to work through. The excuse-making of some of these men – PTSD, alcohol and drugs, and so on – and the way these excuses have been accepted while women have suffered and died is gobsmacking. The thing that most bothered me during the pandemic, particularly the lockdowns, were the women trapped in these violent (in Australia we are moving from using “abuse” to “violence”) households. I found it terrifying to think about.

I like your recommendation about the text version being better. In some works, the textual clues can be critical to our understanding of a book.

LikeLike

I want to say you mentioned See what you made me do when I reviewed No Visible Bruises. I think the research had similar goals and results. The only problem is we are still not talking about domestic violence openly. America (and I’m sure other countries) is very much a place of “not my family, not my business, not my problem.” We still think that when the police show up because a violent person was beating on their partner that it’s the partner’s fault for not leaving. That, in a way, they are “asking for it.”

Why has the verbiage moved from “abuse” to “violence”?

LikeLike

Oh yes, I probably did!

It’s all moved beyond “not our problem” here. The police, admittedly, have been slow to change, partly because the law and other systems, didn’t support them, but it’s happening now. There’s a lot of discussion about terminology here but “violence” is now preferred because “violence” is a more powerful term and there’s acceptance that, for example, emotional and psychological abuse (or coercive control) are forms of violence – and that we should name it for what it is. “Coercive control” is now making its way into the various statutes.

LikeLike

It seems to me the police, here as in the US, automatically side with the guy, the abuser and are very slow – often as here, too slow – to offer protection to the abused woman, let alone to a Black abused woman. Sadly, for all the talk we don’t seem any closer to putting the systems in place to get around this. Further, there is a story in today’s papers, of police perpetrators of domestic violence using their access to police databases to perpetuate their control of their victims.

LikeLike