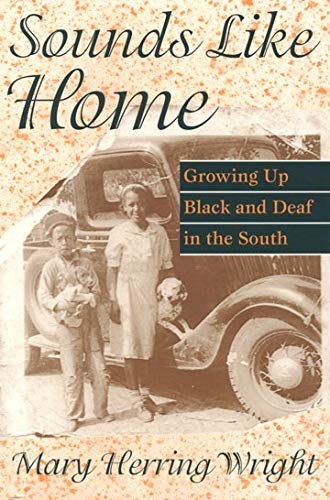

Mary Herring Wright (she/her) was born in 1923 in North Carolina. She loved playing with her many siblings and cousins in a town she describes as having both Black and White residents that were pretty much all related anyway. As a girl, she had sudden onset health issues that led to her becoming deaf. Mary’s mother was an advocate for education and convinced Mary to attend the North Carolina School for Black Deaf and Blind Students. At the time, residential schools for D/deaf children were a place you sent your kids, not dropped them off. In the fall, children boarded trains and buses and headed to school, and they didn’t return until spring. In Sounds Like Home: Growing Up Black and Deaf in the South, Herring Wright shares her experiences.

Herring Wright was born hearing and spent several years attending the local public school for Black children in the 1920s. She loved her siblings, and life seems pleasant on the family farm where they grow strawberries and other crops. In stark contrast to the Black Deaf parents in the memoir On the Beat of Truth, Herring Wright’s family appear financially comfortable. Her father gives her money to buy new clothes for school, her mom sends her a dollar for spending (most items cost a nickle) or she gets huge boxes mailed to her for Christmas stuffed with toiletries, comic books, and food when she’s away at Deaf school.

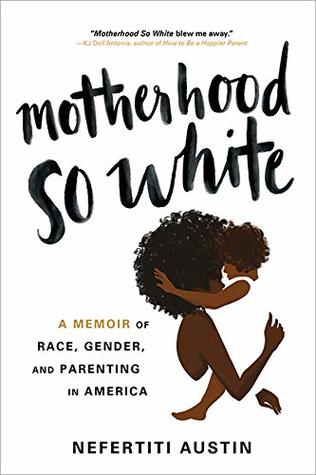

In a small town, with her sizable family, Herring Wright is surrounded by people. Thus, her early chapters are full of names, oftentimes without context. Some folks are neighbors or cousins, some are new adopted siblings who come and go. Sharing care of children among several families is not uncommon in the Black community (see Motherhood So White), but I quickly lost track of who was who as the author simply used first names. I admit I skimmed the last chapter in Part 1 because it was clear there were a lot of caring folks and that Herring Wright enjoyed her pre-school days, but no introspection or significant events.

After she becomes Deaf, Herring Wright is sent to the state’s residential school for D/deaf and Blind children who are Black. She always calls the day she leaves for the school “the dreaded day of departure.” Why does she hate the school so much? I never got a good sense of her feelings because the emotional reflection is lacking. Instead, the author focuses on people and events: she did this, then they did that, etc., mostly in the sleeping quarters. Little time is spent on class, learning ASL, or homework.

There’s more emphasis on names than on significant events. In one part Herring Wright describes who’s dating whom: her and Leon, Jessie and Clifton, Madga and Don, Buckwheat and Robert, Margie didn’t want a boyfriend, Odessa was a player, and Flossie was like a sister to everyone. What does it matter to the reader that we get this list of people dating? The girls aren’t even distinguishable at this point, other than Hazel the bully, who has exited the story.

(An interesting connection for those of you follow Grab the Lapels regularly is that Thomasina Brown, mother of the author of On the Beat of Truth, was at the North Carolina School for Black Deaf and Blind Students at the same time. Thomasina was a teacher while Herring Wright was still a school girl).

Summers were spent back on the farm. The author mentions how she and her mother “talked and talked” but doesn’t explain how they accomplished this. The author can speak still because she was born hearing, but can’t hear anymore. The mother can hear but can’t use ASL. Since Sounds Like Home presents itself as being about “grow up Black and Deaf in the South,” why not explain what relationships with hearing people look like?

There was one moment in which the author compares White D/deaf school to the Black D/deaf school, and thus we do learn about race in the South as it connected to D/deaf people at this time:

Instead of long rooms with rows of beds, all with white spreads and only shades at the windows, they lived in family-type houses with only a few bedrooms to each building and two or three to a room. Each house had a nice homey living room, a dining room with white tablecloths, and china, silver, and glassware instead of bare tabletops and metal plates and cups we were accustomed to. The bedrooms has pretty colored spreads and ruffled curtains. The auditorium was beautiful with a sloping floor, comfortable individual seats, and a stage with rich red velvet curtains and floodlights, plus a heated swimming pool and gym in another wing. Ours was a level floor with hard wooden benches and no stage or curtains.

A closer inspection of the author’s feelings, instead of one big compare/contrast paragraph, and why Herring Wright felt those feelings, would have given the book more heart. As is, it reads more like a historical artifact you would use to create a family tree or a timeline. Perhaps I was the wrong reader for Sounds Like Home?

CW: The racism inherent in having unequal schools. There are no scenes in which Herring Wright describes blatant, direct racism (verbal, physical)

Sorry that this wasn’t what you were looking for – as you say, it sounds like one of those reader/book mismatches that happens from time to time. An interesting historical artifact, though!

LikeLike

Absolutely! If I were doing a research project, this work would have been helpful as a time capsule. I looked more into her follow-up memoir in which she helps during the war effort, and reviews claim it’s the same style of this happened, then this, then this, etc.

LikeLike

Too bad this was disappointing. Sounds like the author was going for more of a personal memoir than a broader scale examination of her experiences.

LikeLike

I think that because Deaf experiences are important to record, especially people who are Black, which actually has its own dialect in ASL, the book reads as a bit dry. Maybe more like something you would use for research and less as something to read because it is compelling.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a shame this didn’t give you more engaging content. How fascinating about the Black dialect in ASL.

LikeLike

There isn’t as much scholarship on black ASL as one might think, so everything people are doing to study it and preserve it is that much more important. Here is the work that they are doing with Gallaudet University: http://blackaslproject.gallaudet.edu/BlackASLProject/Welcome.html

LikeLike

Hmmm was this book self-published? It sounds like a good editor could have coaxed some more emotional reflection from the author quite easily – she just needed to be promoted in the first place!

LikeLike

The memoir is published through Gallaudet University. It’s possible that she worked on the book largely alone, or perhaps editors didn’t want to interfere with her memory by asking her to go deeper. After thinking about it and the comments folks are making, I’ve come to see it more as an important historical document.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s a shame when a memoir falls short like this, particularly when you were reading it partly “for work”. This sounds a bit like – though different from – the Tracy Austin memoir that David Foster Wallace criticises for lacking introspection.

LikeLike

I never thought about how much introspection a memoir requires until I read Let’s Pretend This Never Happened, a funny memoir by Jenny Lawson. After a while, I did not enjoy it as much, but wasn’t sure why. Then, I read her follow-up memoir, Furiously Happy, in which she describes her husband gently pushing her to answer WHY she does or thinks things, and that second book was so much better. If we’re not asking questions about what we’re doing, it’s basically a list of events memoir.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, that’s right isn’t it. And some people are more naturally introspective than others I think. I tend to think but when I write, like letters, I feel I report too much. Finding words to convey inner thoughts clearly is tricky I think.

LikeLike

That’s a good point. I personally find journaling tedious because it comes out like a book report of the day’s events.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yep! The only time my journaling hasn’t is when I’m in a highly emotional state, like after my sister died or after my first child was born!

LikeLike

Good point. I don’t get these folks who journal every day, like Matthew McConaughey or David Sedaris or Mark Twain.

LikeLike

No, me neither!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Melanie Page.

LikeLiked by 1 person