After reading A.M. Blair’s newest novel, Nothing But Patience, a retelling of Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility, I was interested in reading Austen’s original. I do believe I was assigned Pride and Prejudice twice in college and could never get through it, and when I read Northanger Abbey aloud to Nick, I wasn’t terrible impressed with the obsession with going to the “pump room” — what is that??

But, with Sense and Sensibility I had a few things going for me: 1) Having a sense of the plot thanks to Blair’s book, 2) Doing a buddy read with Roshni, and 3) Checking out an edition that has side notes instead of footnotes or end notes. And I enjoyed myself!

Sense and Sensibility was published in 1811. My copy is annotated and edited by Patricia Meyer Spacks. The novel opens on the Dashwood family. The patriarch has died, and though his will leaves everything to his son, John, he asks that John be kind and take care of his step-mother and three half-sisters: Elinor, Marianne, and Margaret. Sure, dad, he says. But when John’s wife, Fanny, hears what John has promised, she convinces her husband to reduce the amount per year that he will give each woman until it’s almost nothing. John Dashwood, money focused, starts to side with his wife, even booting the his step-mother and half-sisters out of their family home: “. . . [John]so frequently talked of the increasing expenses of housekeeping, and of the perpetual demands upon his purse, which a man of any consequence in the world was beyond calculation exposed to, that he seemed rather to stand in need of more money himself than to have any design of giving money away [to his step-mother and half-sisters].” So, they are forced to rent a cottage from Sir John Middleton.

During their early days at the cottage, the Dashwood women get to know Sir and Lady Middleton and some of their friends, especially Colonel Brandon. Colonel Brandon is a do-the-right-thing stoic but has a crush on Marianne Dashwood, who is seventeen. But Colonel Brandon is THIRTY-FIVE! Ewww, what an old corpse (I object!). Or so Marianne thinks:

“. . . if he were ever animated enough to be in love, must have long outlived every sensation of the kind.” She says, “When is a man to be safe from such wit, if age and infirmity will not protect him?” And the response from is Elinor is, “I can easily suppose that his age may appear much greater to you than to my mother, but you can hardly deceive yourself as to his having the use of his limbs!”

Basically, Colonel Brandon, at thirty-five, is too old to have ever had loving feelings, and what’s the point of being old and disabled if those things don’t keep you from getting crushes when you’re practically deceased? I laughed so hard here, and had to read this passage to my spouse, who is creeping up on thirty-nine. He did not appreciate it when I asked about his limbs.

In case you couldn’t guess, Marianne is the “sensibility” character for the most part, the one who feels everything so deeply. She cries goodbye to a tree when the Dashwood women are kicked out of their home. She practically wastes away when her romantic feelings are denied. Elinor, however, slightly older, is the pragmatic “sense” of the novel (again, for the most part). She looks at everything logically, waiting for evidence and maintaining composure in public. She hates small talk; we would be friends. Oddly, she has romantic feelings about Edward Ferrars, brother to money-grabbing Fanny.

The Dashwoods also meet John Willoughby (everyone is named John in this book), a handsome rogue who lives nearby with his aunt. He woos Marianne with promises and his cute face, and she falls in love with him. They are all but promised to be married when Willoughby leaves the area without much ado. Marianne is destroyed. Throughout the rest of the novel we learn about the histories and romantic feelings of Colonel Brandon, John Willoughby, and Edward Ferrars and how that relates to Elinor and Marianne (Margaret, the youngest sister, is an unnecessary character). Readers are misled, wait for reveals, and learn the truth. It was just twisty enough to keep me interested, but I wasn’t overwhelmed with the cast list. Because so many folks are related, it was easy to think, “Oh, that’s so-and-so’s daughter.” Plus, the characterization of almost everyone is varied enough that each person stands out on their own.

Though the “hero” of Sense and Sensibility is likely Elinor, I was so focused on Marianne, who reads like a modern girl: funny, mean, emotional, passionate. She always has something to pick on in regards to Colonel Brandon, who will be her obvious match in the end:

“She was reasonable enough to allow that a man of five and thirty might well have outlived all acuteness of feeling and every exquisite power of enjoyment. She was perfectly disposed to make every allowance for the colonel’s advanced state of life which humanity required.”

If you’re new to Jane Austen, I recommend you start here, and get yourself a the same copy I had. The side notes gave contextual and comparative information. For instance, the amount of money John Dashwood receives after his father’s death is 80,000 pounds, equivalent to over sixteen million pounds today. This gives you a sense of what “wealth” means at the time. Also, when the Dashwood women are thrown out and “ruined,” we’re not talking homelessness, working as prostitutes, and living in tiny rooms with no fresh air. We’re saying they won’t be on the marriage market with other rich people in the same way. I always thought Austen’s characters lived in some weird version of poverty until I encountered this edition.

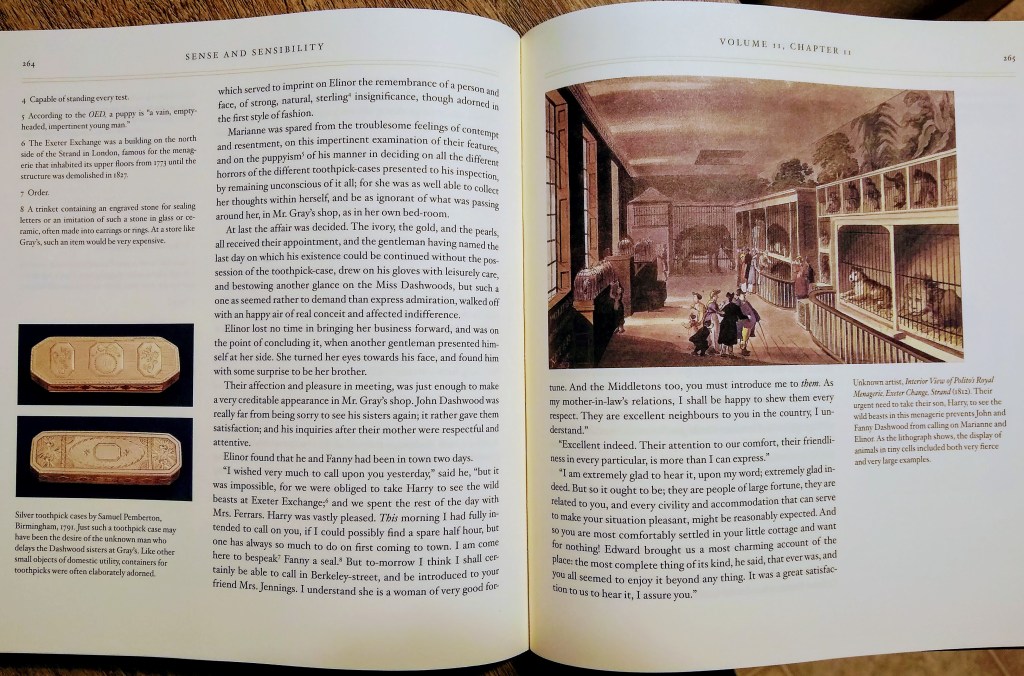

Not only does the editor include side notes (a revelation!) but images that show you what a character might have worn or what the building where they lived may have looked like. In my example below, you see a picture of what a toothpick case would look like at the time (an item a character purchases) and a painting of “the wild beasts at Exeter Exchange” that John Dashwood takes his family to (so you get a sense of what a place might look like).

A wonderful story made even better with the editors annotations. I also read that Patricia Meyer Spacks has a similar book for Pride and Prejudice, so I may have to give it a whack again.

Oh annotated versions of Jane Austen sound so fun. I am going to have to give these a whirl.

x The Captain

LikeLiked by 1 person

There are many, many annotated versions, so I recommend one that includes images and the most convenient version of footnotes (like, not in the back of the book).

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve never read Austen, the Bronte sisters or Woolf. All on my list to get to eventually but I only read one classic a year on average. I’m currently working on On the Road as my lunch book at work. I should make it a goal to read one of the above ladies when I’m finished with Kerouac.

LikeLike

I never finished Wuthering Heights nor Pride and Prejudice. I did finish one Woolf novel and I was like, “Is that it???” I actually prefer Dickens quite a bit, as he is so funny.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have not read him either. There is a very long list of classics that I have not gotten around to. :3

LikeLike

I think Dickens is much easier because whether you know the cultural norms of the time period or not, he’s still really funny. Like, his characters can be pretty salty in a way that’s funny today.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s good to know. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Actually, Austen is pretty funny too, but in a witty rather than obvious way like Dickens (at least, she is to me!)

LikeLike

I do think I miss the subtlety of Austen’s humor. When people find Pride and Prejudice funny, I feel puzzled. Then again, I don’t know the social rules that make some of her character’s funny.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I guess if you don’t get her humour, you would miss a lot. I suppose the annotations don’t really help there? I would say some of the humour relates to social rules, but some relates to human nature. An example of a quietly humorous thing in P&P concerns Charlotte Lucas, who married Mr Collins because she knew that he was her best chance of not being unmarried and a drain on her family. When Elizabeth visits her, Charlotte shows her her house and explains her life, and the subtle message is that she knows he’s a silly man but she manages life in such a way to spend as little time with him as possible, and we see the light dawning on Elizabeth, who could not understand how her (older) friend could accept such a marriage or make it work. This scene never fails to make me smile.

LikeLike

I do remember that scene and I always feel sad, but I suppose I’m thinking of women now as opposed to Charlotte seeing that she has the best of both worlds.

LikeLike

I think you are supposed to think of women and feel sad – but it is humorous to see how she manages her sad situation, if that makes sense? (In other words I don’t think she HAS the best of both worlds but she MAKES the best of her world.)

LikeLike

Definitely; she’s a product of her environment and she works within that context. If she can be the system, so be it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m glad Marianne was your favourite. Elinor is so forced to mother her (their mother is useless) that she ends up a bit of a drip – though as you imply, she does get to show some “sensibility” herself towards the end, albeit in the privacy of her bedroom. On my last re-read, I thought S&S was pretty standard YA, I don’t suppose you’d be willing to stir Sue up and agree with me.

LikeLike

I know there’s a lot of conversation around what YA is, and here is my general feelings about it: YA is written for young adults to read. It is not necessarily about young adults, as there are many novels about young adults that have more advanced sentence structures and grammar. Therefore, I wouldn’t call S&S YA because I never could have got through all the language as a teen. Granted, I never claimed to be a terrible smart teen, either.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well said, Melanie … YA is written for young adults, not just about. I think Austen was writing for everyone. There was no sense, really, in those days of writing for young people, anyhow.

But, I have to say that S&S has always been one of my favourite Austen’s (and one of my mother’s least favourites.) Dare I admit that in “which Jane Austen character are you” I can often come out as Elinor. That may mean I’m a drip – to Bill – but although of course I’d love to be Elizabeth Bennet, who wouldn’t, I don’t mind being Elinor, because she’s such a caring and responsible person. She picks up all the pieces for other people, and doesn’t impose her own on others. I could go on.

And yet, one of my very favourite Austen quotes comes from S&S, and it relates to Marianne. It goes “Marianne Dashwood was born to an extraordinary fate. She was born to discover the falsehood of her own opinions, and to counteract by her conduct her most favorite maxims.” It brings me up every time, because it reminds me about how often I like to pontificate on things I haven’t experienced (like Marianne) only to find, when I experience it, that it’s not quite as I thought! This is why I love Austen so. It’s full of insights like this that don’t change with time.

Finally, the interesting thing about this novel – her first published – is that the opening situation really captures what happened to Jane, her sister and mother, after her father died. They were homeless for several years – moving from place to place – until her wealthy brother provided accommodation on his estate (just like Mrs Dashwood’s cousin did for them.) Austen knew exactly what she was writing about and how terrible things were for widowed and unmarried women.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I identified more with Marianne simply because when I was her age I felt things so deeply and was easily moved. I’m not sure I could sustain that mode of living now, but it sure was exciting when the burden of living adult life wasn’t on my shoulders yet. I hadn’t thought of Elinor as being someone with opinions who hasn’t experienced the situations about which she has opinions, but you’re right. I wouldn’t call her a drip; she’s trying to keep her family together by avoiding any improper situations that would make things worse for them (I’m now picturing Moll Flanders, a novel I read at Bill’s recommendation, even though Moll was so, so far below where the Dashwoods were).

In my copy, the editor/annotation lady noted that Austen knew the opening scenario well, but I didn’t realize Austen was also at the mercy of a relative. It’s odd to think it seems like she has nothing because a brother is dangling his “good will” over her head.

LikeLike

It’s Marianne who has opinions before she has experienced the situations about which she has opinions. (Did I use the wrong name there? I haven’t got my original comment on the screen where I’m replying.) I meant to say that I love Elinor, but it’s the description of Marianne that is one of my favourites in Austen! (I have read Moll Flanders, but decades ago. Much bawdier and from a different class to the Dashwoods, as you say!)

The situation Austen and her mother and sister were in was such a common one in those times – we HAVE come some way since then, thank goodness!! We are not quite sure why the brother took so long to offer them a home, but we think it had something to do with the death of his wife (after the birth of her 11th child in 15 years!) One theory is that she didn’t much like Jane, and so Edward only felt he could do something for them after she’d died. But, he also had some financial challenges to do with his property at that time, so that may have been an issue too. We’ll probably never know.

LikeLike

Perhaps you did say Marianne! I was thinking that it doesn’t seem Elinor has much experience. For instance, when she falls in love and feels sad, but keeps it to herself. However, before, when Marianne was in love and had her heart broken, Elinor seemed to have answers but had not experienced heart break herself.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, Elinor is inexperienced too but she is both mature and empathetic I think. Marianne is loving and kind but not very mature and only able to see things from her own youthful perspective. A bit like her Mum really! Her mum is older but a little inclined to be romantic. Poor Elinor carries the can for the family.

BTW you made a good point, I meant to say, re Margaret. Is she really needed? She has been omitted from adaptations.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh, and sorry if I’m labouring things. I can do that … particularly with Austen.

LikeLike

Hahahaha, you’re fine, Sue 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

This was the second classic book that I ever read. My grandmother gave me Pride and Prejudice and I loved it so much I went and got Sense and Sensibility from the library. I was probably too young to catch the nuances but this did not hinder the start of my love for Victorian literature. ❤️. Wonderful review!

LikeLike

Thanks, Tessa! I absolutely hope that you and your grandma watched the Colin Firth version of Pride and Prejudice together and giggled when Mr. Darcy has the wet shirt. I’m glad that I got the annotated version just so I could latch some of the information from that time period onto what I understand about the world today. That’s typically my hang up with classics: the world is unrecognizable from my own.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m glad the annotated version did the trick for you! Whatever works. Austen is my fave, as you probably know. Just reading this makes me want to reread it. Have you seen the film? It’s THE BEST, and Eleanor (Emma Thompson) is very droll. I was about 16 when it came out and it was all very swoon-worthy. Back then I was sad with Marianne about Willoughby (I thought he was dreamy) but now I’m all about Colonel Brandon (Alan Rickman -sob!) And when Eleanor bursts into tears at Edward’s declaration I also burst into tears. Gah! I’ve gotten all worked up! Now I’m going to have to watch it again.

LikeLike

LOL, Laila, you are a treat. I also love Alan Rickman and am sad that I’ll never see him in anything new again. I have not seen the film, though I should get on that! My only concern is the editor of my copy of S&S pointed out how the director of the film version did lots to make it more romantic, whereas the book is more about practicality in marriage and alliances.

I forgot you were an Austen lady. I always think of you as a Pym lady. I’m more of a Dickens gal myself. He is a HOOT.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh, it’s DEFINITELY romantic! 🙂

I am an Austen lady AND a Pym lady. They’re in my top 5. Dickens is fun!

LikeLiked by 2 people

So glad that you enjoyed this and that the annotated edition worked for you! This is one of my favourite Austens (though my absolute favourite is Persuasion). I much preferred Elinor to Marianne, whom I found very irritating when I was a teenager – though I suspect I would have more sympathy for her now (seventeen is, after all, very young, and I don’t think I really realised that when I was fifteen). The stuff about Brandon’s extreme old age made me laugh – I mean mid-thirties was older then than it is now, but still.

I second Laila’s recommendation of the film – it does take some liberties with the text, but I love it anyway. Emma Thompson is such a great Elinor. And it makes Margaret into a more interesting character!

LikeLike

I can’t tell if it’s funny or awful that I relate to Marianne and her dramatic emotions. That’s just so realistic for me. I could easily be in love with a different boy in every period at school. LOL!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yep, I’m a Persuasion lover too, and I’m also an Elinor fan, and found Marianne a bit silly. I was always too sensible, I’m afraid. Anne Eliot and Elinor are favourites of mine, in other words. The quiet, caring ones!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I read A.S. Byatt’s rewrite of Persuasion, though it’s been so long ago I’ve forgotten a lot of it. I do remember that she really pushed this idea that color could be an important theme, which felt a liiiiiittle ham handed to me.

LikeLike

Yes, that was The Jane Austen Project. I’m afraid I didn’t read any of them. Val McDiarmid did Northanger Abbey!

LikeLiked by 1 person

That illustrated and annotated edition looks excellent. Of course I grew up near a town with PUMP ROOMS! so they are not a mystery to me, however just like when I introduced the ford near me to my blog, they can bamboozle the non-UK reader! I love Austen, Northanger Abbey was my favourite for a long time because I studied the gothic novels it’s satirising, but I also love this one (Team Elinor!).

LikeLike

Oddly, I thought the male characters in Northanger Abbey were much more interesting, with the cleverer dialogue and such. That surprised me, given that it’s Jane Austen!

LikeLike

My Mum had a special love for Northanger Abbey. There are some in my Jane Austen group who could never understand that. I like it a lot. To be honest, I can’t understand any Jane Austen fan not loving all her books!! Haha.

LikeLike

I hate to say it, but I did want something at least a little ghostly to happen. I suppose at this point the characters are meant to be wrapped up in the “pulpy” romance ghost stories of the day rather than true occultists interested in spirits, which was all the rage in the U.S. after the Civil War.

LikeLike

This makes me laugh Melanie. The last think I want is ghosts. BTW One of the reasons Mum liked Northanger Abbey was because she identified with eager young Catherine.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That looks like a fantastic edition to read! I am laughing at the idea of someone aged 35 being too old to have feelings or use his limbs but I probably felt something similar when I was 17!

LikeLike

Oh, I about died laughing because I’m 36, and then I read it to Nick because he’s going to be 39 here in short order. This was a great edition for sure, and I’ll never try another classic without some annotations on the sides. It makes that big of a difference.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This edition you have looks gorgeous!!! I like the idea of sidenotes, I sort of detest endnotes and footnotes, I find it interrupts my reading.

Also, I would never really find myself siding with people who are ageist, but I wonder if, a 35 year old man would be like, the modern day equivalent of a 50 year old, just becuase their life spans were so much shorter at the time? And like, their quality of life, nutrition, etc was so much worse, maybe a 35 year old man really looked old and gross? I have no idea, just throwing it out there as an option haha

LikeLike

Oh, Anne! You’re terrible! LOL.

LikeLiked by 1 person

hahah

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m glad my story encouraged you to read Sense and Sensibility! I haven’t been on social media much (life has been a bit overwhelming), so I’m just seeing this now. I agree with you that Sense and Sensibility is a great place for readers to start. Elinor is the character I identify with the most out of all of Jane Austen’s characters (and that’s partly why I made her racial/ethnic identity so similar to mine). She and I are both pragmatic, somewhat boring, older sisters.

LikeLike

I’m really glad I took the time to find a copy that would explain the essentials to me that I would not get from being a 21-century reader. There weren’t too many analysis comments in the side-notes. Thank you for writing a book that inspired me to give Jane Austen another try!

LikeLike