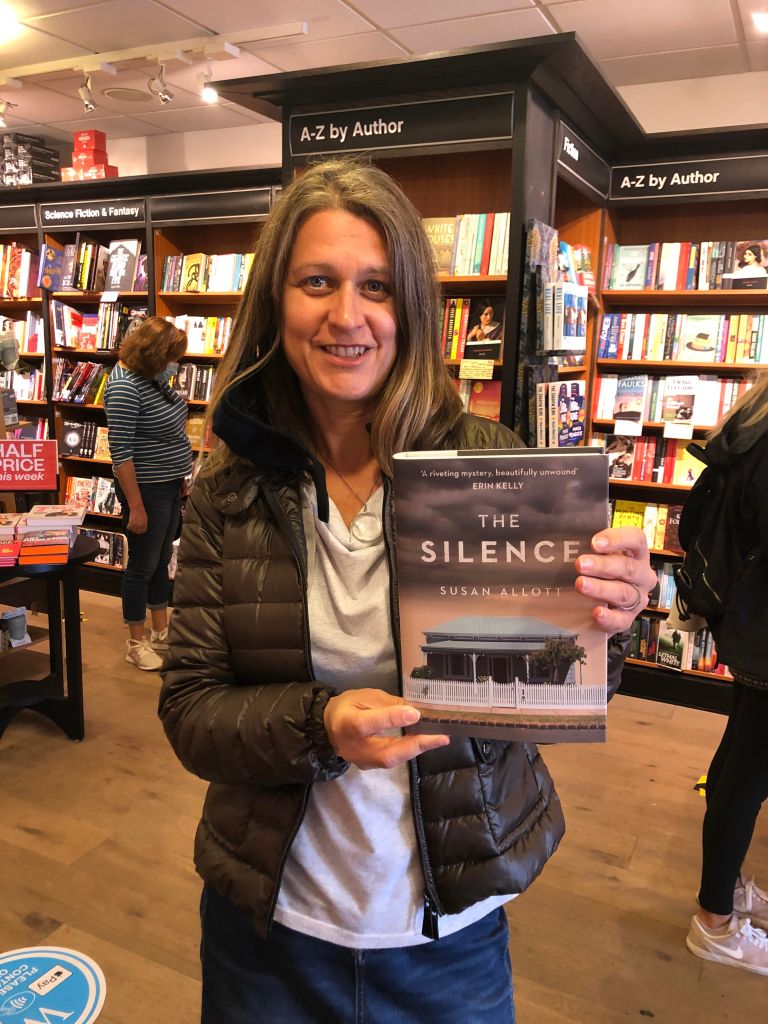

Meet the Writer is a feature for which I interview authors who identify as women. We talk less about a single book or work and more about where they’ve been and how their lives affect their writing. Today, please welcome Susan Allott. Most recently, she is the author of The Silence, which I review in 2020 as part of Reading Australia Month. Allott can be found in a number of places across the internet, including Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and BookBub. More information about the author and where to purchase The Silence can be found on her website.

Grab the Lapels: What kind of writing do you do? What kind of writing do you wish you did more of?

Susan Allott: I consider myself lucky that I don’t have to write anything other than fiction for a living any more. I was working part time in the nonprofit sector while I wrote The Silence, and I had to write a lot of policy briefings and articles for work, the kind of writing that has to be informative and sometimes persuasive but never creative. I don’t miss that at all. It was sometimes hard to switch from that type of writing to writing creatively; it uses a different muscle. I was made redundant in 2018, and I now think of it as a gift from the Universe because it allowed me to focus on writing five days a week. My book sold to Harper Collins early in 2019, and I’ve been a full-time writer since then.

I write literary thrillers. I say that as if I’ve got a huge back catalogue. In fact, I’m currently writing my second novel and the first is out in hardback, so I’m still new to this. But literary thrillers seem to be my sweet spot, as a reader and as a writer. I love literary fiction, with its well-drawn characters and considered prose, but I also love plot-driven fiction that keeps me reading late into the night, desperate to know what happened. So, I love books that bring those two qualities together, and that’s what I try to write. I’m enjoying writing in this genre, creating atmosphere and suspense and mystery. Luckily there seems to be a market for it, too.

I often wish I had the time and headspace to write short stories or maybe to think about writing for film or TV. But I’m a painfully slow writer, so I can’t afford to slow the process down any more by working on anything outside of my manuscript. I also have a family who like it when I occasionally look up from my laptop and pay them some attention. So for now, writing my second novel is all I have time for. Maybe one day I’ll have an idea that would work perfectly for film and I’ll skip the novel and go straight to the script.

GTL: In what ways has academia shaped your writing?

SA: I love academia.I have a degree in English Literature and a Masters in Media & Communications. I’m an alumna of the Faber Academy 6-month course, which was great, mostly for the belief it gave me in myself as a writer and in my novel as something that could be good enough for publication. But I actually think the best course I’ve done in terms of improving my technique as a writer is the Jericho Writers self-edit course, which was online and reasonably priced. It took my writing to the next level, and every time I notice that my prose feels dead on the page, I go back to the lessons I learned on that course.

I loved creative writing at school, and was genuinely shocked when I got to A-level and realized there was no creative writing component to the English curriculum. It was all just reading other people’s books and analyzing them. I was devastated, but I didn’t tell anyone. I was embarrassed to admit that I all I wanted to be was a writer. Creative Writing degrees didn’t exist back then, as far as I knew. So for several years I didn’t write anything except essays about the merits or otherwise of other people’s writing. The longer I left it, the harder it was to pluck up the courage to start writing creatively again. I eventually signed up for a creative writing course the year I turned thirty. I was rusty but very relieved to have finally got back to writing. There’s nothing as miserable as a writer who isn’t writing.

My absolute dream would be to go back to studying alongside my writing, maybe film studies or history of art, just for the love of it. I think kids are too young to appreciate university when they first leave home, and those years are often more about meeting people and having fun than about study. I would kill to go to university now and read books all day, go to lectures, sit in the library. When I was twenty all I wanted to do was go out dancing and sleep all day. And that is exactly what I did.

GTL: In what ways has life outside of academia shaped your writing?

SA: I think all my life experiences have shaped my writing, as well as the experiences of people I know, my friends and extended family. I don’t write about my own experiences or those of other people in a literal way, but I do draw on them and then fictionalize them. The obvious example is that I lived in Australia for a while in my twenties, but was very homesick and eventually returned to London. So as a starting point for writing The Silence I drew on that experience of alienation from a culture that on the face of it was similar to my own. But The Silence isn’t really about my experience of being in Australia; I used my own experience and amplified it, or toned it down, or completely made it up in some ways. The end result is a fiction that contains emotional truth, rather than literal truth.

After The Silence was published my dad talked to me for the first time about his grandparents, whom I never knew. I won’t say what he told me because I don’t have his permission to do that, but some of it was close to what I wrote about in The Silence. I do believe that we carry the experiences of our ancestors with us in our DNA. We know their stories on some level and we have their trauma in us. If we’re not careful, we repeat their mistakes.

GTL: What was the first piece of writing you did that you remember being happy with?

SA: I can remember at primary school I used to look forward to my English teacher’s feedback on my stories, knowing that I’d written something good. I figured out the relationship between hard work and reward quite young. I always got a big kick out of writing something as good as I could make it, really polishing it, and finding that sometimes it was better than I thought I was capable of. There’s a real pleasure in that, when you look at a line you just wrote and think, that’s good; where did that come from?

I pretty much live for that experience of being in a state of bliss with my writing, where it’s flowing and working and I’m not in the way of it. It’s quite rare, unfortunately. The other thing I’m discovering lately is the pleasure of connecting with readers. Getting a review online (yes, I do read them all) where the reader obviously understood and appreciated my work is just wonderful.

GTL: What did you want to be when you grew up, and does this choice influence your writing today?

SA: I only ever wanted to be a writer. I think that’s partly due to a total lack of career guidance. I remember telling a careers advisor that I loved books, and he said in that case I could be a librarian, a teacher or a journalist. I had no idea the publishing industry existed until I started writing a novel and looking into how to get published. I thought books just ended up on shelves somehow. If I’d known the job existed I think I might have wanted to be an editor, or some other role in that sector. But then if I’d loved my career I might not have had such a strong urge to write. So maybe it’s not such a bad thing.

GTL: Are there aspects of your writing that readers might find challenging to them?

SA: I hope so. It’s been interesting to see the reactions from readers around the world and to realize that most people didn’t know about Australia’s policy of removing First Nations children from their families. The policy was carried out quite openly until the 1970s, with very little objection from journalists, politicians or the public. Most people who look back on that time say they had no idea it was happening. In The Silence I’m suggesting that maybe there were people who knew about it and who managed to deny the knowledge somehow, choosing not to process it or to forget.

I wanted to know what that level of denial might look like in a community. The residents of Bay Street are forced to confront what Steve is doing: he cries on the veranda in broad daylight, then later he brings a baby home. This prompts a few questions and comments. Joe eventually makes some phone calls. But this is discomfort rather than outrage, and it soon settles back into silence. Why is that? I wanted the book to ask that question, to prompt the reader to think about it.

I don’t think it’s too controversial to say that as a British citizen I’m ashamed of many aspects of my country’s imperial history. Maybe it’s slightly more controversial to say that I’m angry not to have learned about it in any depth at school, despite studying history up to A-level. My kids aren’t learning about this aspect of their own history at school either. People are so scared of saying the wrong thing about this, and the result is silence. That silence is how we repeat the mistakes that our ancestors made.

Personally I like books that make me think without driving their point home too strongly. I hope The Silence is entertaining above all else, and moving and thought provoking at the same time. That’s what I was aiming for.

The best book on the removal of Aboriginal children from their families – for ever in many, many cases – is still Follow the Rabbit-Proof Fence, by a woman whose mother was stolen and then the author was stolen from her mother (also a movie). The Stolen Generations over the last two or three decades has also been the subject of many memoirs, but I’m glad Allott is dealing with it too. Children are too often the victims when right wing/racist governments attempt to penalise minorities.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree! The film Rabbit Proof Fence had a huge impact on me when it was released. I read the book afterwards. Both were a strong influence on The Silence.

LikeLike

Oh, that’s such an interesting connection. I mentioned in Bill’s comment that I remember his review of Fence but didn’t get it. I just bought an e-book copy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’d love to know what you think of it.

LikeLike

I’ll be sure to post a review. Bill’s got me reading more Australian lit now than any other time in my life. Up soon is Lantana Lane by Eleanor Dark.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Melanie, that’s great that you’ve bought Rabbit-Proof Fence (though I might have hoped that it was enough of a classic that it was somewhere in the inter-library system). Your initial comment, 5 years ago, was how could the families let the girls go. But of course they were taken by police and told that it was for the girls’ education (‘as servants for whites’ was left unsaid).

Now I’d better get myself a copy of The Silence. I can’t see that it’s been reviewed yet by an Australian blogger. I checked the cover, Angus & Robertson have used an Australian single storey Federation cottage torn asunder, so that’s an improvement.

Ms Allott I don’t blame you for going home to England. But I hope you are keeping up with Oz Lit (and especially Indigenous Lit which is where all the innovation is), and who knows, if Evie Wyld is any guide we may claim you anyway.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m a big Oz Lit fan and would love your recommendations around Indigenous Lit. Here is a piece I wrote for Crime Reads about my top 10 Australian novels: https://crimereads.com/10-essential-australian-novels/

LikeLike

Ms Allott, I read your post, and after Monkey Grip, which I love (I was a student in inner suburban Melbourne myself in the 60s and 70s) and of course Rabbit-Proof Fence, I’m afraid we must agree to disagree. Interesting that you have two English-Australians there who both have a very tenuous grasp on Australian geography 9my pet hate).

No – I also love the Indigenous Western Australian author Claire Coleman.

Here’s my ten ‘best’ –

https://theaustralianlegend.wordpress.com/2020/08/23/there-is-a-gan-revisited/

and here’s a joint post Melanie and I did on The Slap –

https://theaustralianlegend.wordpress.com/2020/09/19/a-letter-from-america/

The good news is I bought The Silence today, I’m on holidays so I have plenty of time, and I’ll post a review later this month (a blogger friend, Kimbofo at Reading Matters is holding a Southern Cross Crime Month)

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m glad you’ll have some time off for a while so you can read The Silence. It’s quite engaging.

What aspects of geography do folks get wrong? I find it more annoying when writers fail to capture the verbal cadence of an author, and was especially displeased when Neil Gaiman published American Gods, which is full of (duh) American characters (and from the Midwest, no less!) who use terms like “trolly” and “motor vehicle.”

LikeLike

Regional speech is less of a problem (for writers) in Australia, most of the difference is class and ethnicity based, and very few white Australian, middle class writers go down those particular rabbit holes. But the concerns you have with ‘terms’ I have with places. Jane Harper and Evie Wyld, the two English-Australian authors I was referring to, both wrote about places they had never been to and based their ‘descriptions’ on stereotypes which, because I have been there, I found trite and/or inaccurate.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ms. Allott, I just read your piece — I had no clue The Dry was an Australian book, but I know it made a lot of noise in the U.S., so it has some good reach!

LikeLike

I think when I read your post five years ago I didn’t know nearly as much about Australia and the history of its indigenous people as I do now. I also wonder if my comments stemmed from what happened in the U.S> and Canada: Native Americans were told that their children would get an education in English, which may help them assimilate in the developing nation. Many would want this for their children, but it was all false advertisements, of course.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I remember your review of The Rabbit-Proof Fence and have no idea why I didn’t add it back then. It sounded harrowing and frightening, and absolutely worth the read.

LikeLike

“There’s nothing as miserable as a writer who isn’t writing” – that hits the mark! Can also relate to writing your emotional truth rather than literal truth, and working for the feeling of those blissful moments of not getting in the way of the writing, looking back at what you’ve written and thinking “that’s good, where did that come from?” Lol. I’m connecting to and intrigued by A LOT in this interview tbh, Allott is a talented, convincing writer. Melanie, your review of this book was great, but Allott talking about some of the meaning in her book is landing it on my TBR. Thanks to you both for this superb post! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Emily, thanks so much! I love how you connect with these posts as both a writer and reader. I really enjoyed The Silence quite a bit and had a hard time putting it down. Though it has thriller elements, I wouldn’t call it a thriller. Also, even though Allott is from the U.K. and the book is set in Australia, I had an easy time getting a library copy in the U.S.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I really tend to like literary thrillers, that focus mainly on character and theme and have a few fun thriller elements thrown in, so this book sounds like a good fit for me. And thanks for the tip about it being easy to find in the US- I’ve just checked and it looks like it’s available through my library too, so I’ll definitely pick up a copy when I can!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Woohoo! Looking forward to your review!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love this idea of carrying our ancestor’s actions in our DNA, and the fact that we need to be careful or we will repeat their mistakes!

Alllott’s musing that literally thrillers is a popular genre-um hell yah! And I doubt it’s going away anytime soon 🙂

LikeLike

The word “literary” is getting tagged on to so many genres! It drives me bonkers because it implies a genre book is not fully “genre” if it’s good. However, I totally understand that we’re in a place with readers and publishers that it becomes necessary to add “literary” to genre books, or it may not get the attention of folks who are looking for quality lit and aren’t interested in a genre they perceive as typically being poorly written material.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s a good point, I find the line between ‘literary’ and ‘everything else’ is getting more and more blurred. Personally, I’ll describe something as literary if it isn’t really plot driven, but that’s pretty general haha

LikeLike

It’s it’s not plot-drive, I tend to call it character-driven. But who knows. The whole conversation, at the end of the day, baffles me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This has made me all the more intrigued to read her book. The idea that our ancestors’ trauma somehow makes its way into us even when we’re unaware of it is a sobering one. And I would love to return to university at this point in my life, just to learn!

LikeLike

Part of me wants to return to college because I would be so good at it now, lol. I really hope you guys pick up The Silence; many folks have noted that this interview has made them more interested in the book. I had a hard time putting it down.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’d love to go back and just learn, without the pressure of grades and What Are You Going To Do When You Graduate???

LikeLiked by 1 person

I suspect more people knew what about the stolen children than ever let on. Mum grew up in a working class rural town and they knew it happened. Her own mum, when she and her brother were being ‘naughty’, would threaten them with calling welfare to come and take them away, too. There didn’t seem to be a lot of love going around at that time, or that place in Australian history.

LikeLike

Did your mom fear that someone would come get her, or did she not take your grandma seriously? I would be terrified to pieces because it was actually happening and not just a boogie man story.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes my mum was terrified. Parenting style back then often used fear as their main deterrent!

LikeLiked by 1 person