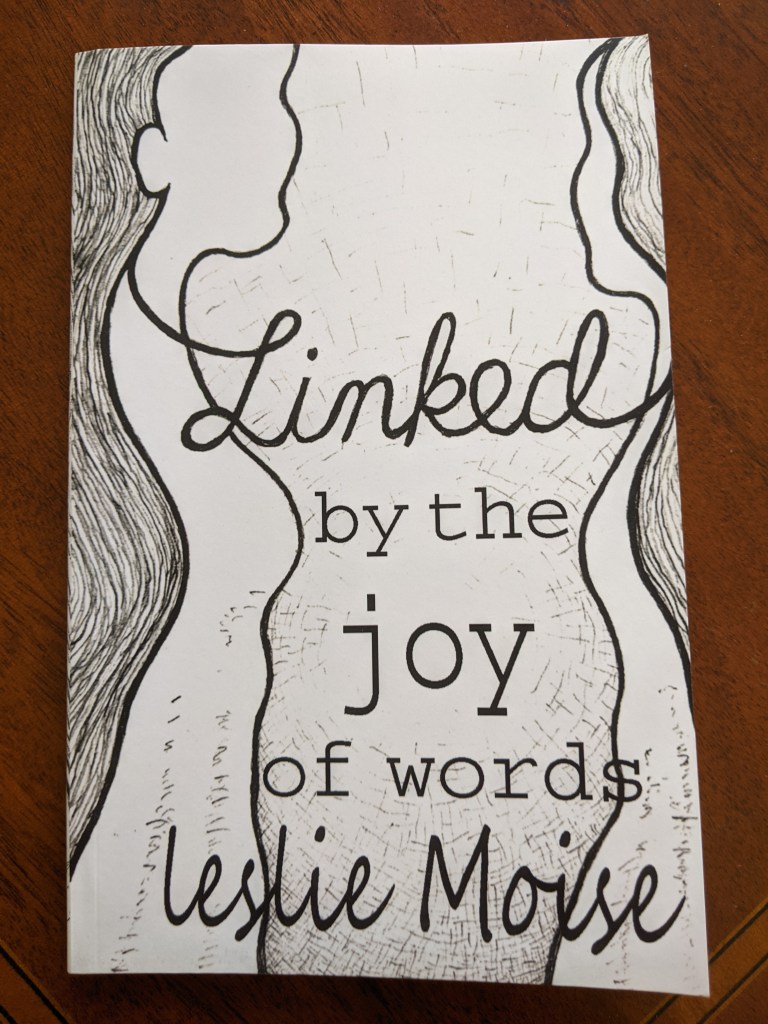

Meet the Writer is a feature for which I interview authors who identify as women. We talk less about a single book or work and more about where they’ve been and how their lives affect their writing. Today, please welcome Dr. Leslie Moïse. Most recently, she is the author of the poetry collection Linked by the Joy of Words. She also writes memoir and fiction, reflective of her Ph.D. that focused nineteenth century women’s fairy tales. You can find her on Facebook and Instagram (where she shares about knitting and equestrian life).

Grab the Lapels: What was the first piece of writing you did that you remember being happy with?

Dr. Leslie Moïse: The first book length manuscript I wrote, a mystery titled Death at the End of the Ride, filled me with such pleasure. “Look at all I’ve written!” I couldn’t understand why publishers kept rejecting it, and with form letters at that. Of course, I was naive to feel so satisfied, even though I had written from my own experience. The mystery drew on my lifetime with horses, since both the murder victim and the protagonist/ detective were horse dealers. And like Sue Grafton, I had chosen to subvert my personal feelings of rage at my ex-husband into this fictional world. But then a friend brought me into a writers group, and before the first meeting ended, I realized why publishers rejected it. I had written a rough draft, not a polished novel.

GTL: What did you want to be when you grew up, and does this choice influence your writing today?

LM: I always wanted to be a writer when I grew up, aside from early childhood desires to become a horse (or a lion.) I read Little Women, and identified with Jo March from the first page. In fact, partway through that first reading, I went out to the sun porch and wrote a really terrible bit of doggerel! I think that was the only time I paused in my reading except for meals and bedtime. Even then, I snuck a flashlight under the covers and read until my mother caught me. Now I feel like I’m finally making that childhood dream a reality. It only took 50+ years!

GTL: Are there aspects of your writing that readers might find challenging to them?

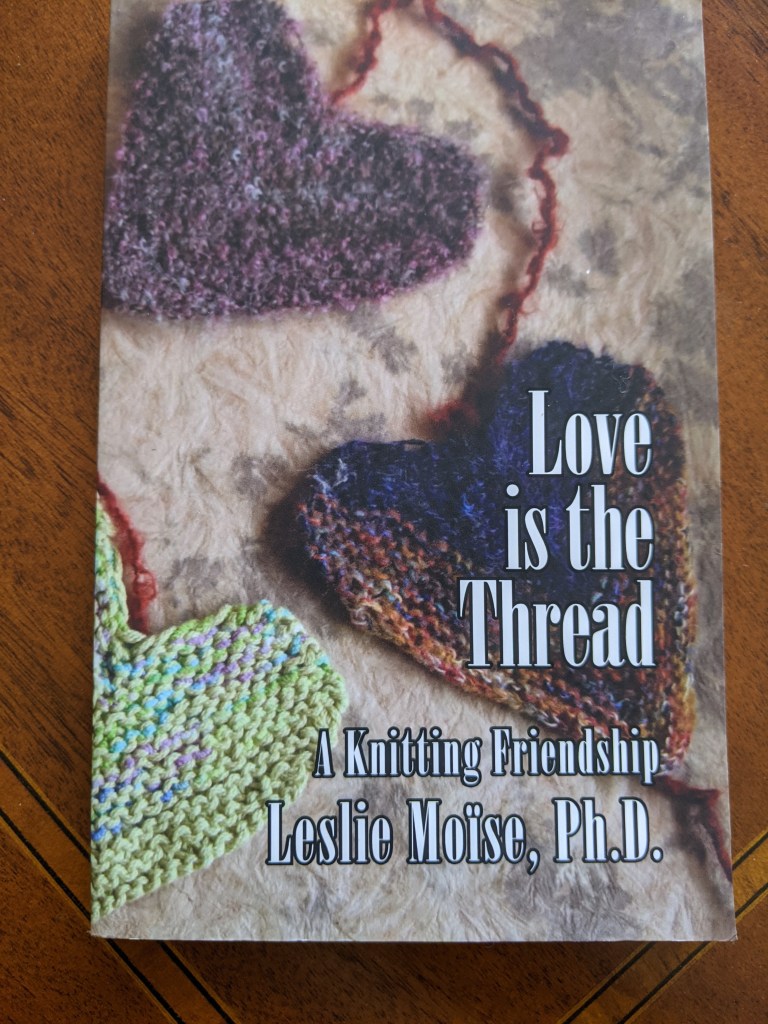

LM: Both my knitting memoir, Love is the Thread, and my poetry chapbook, Linked by the Joy of Words, deal with the deaths of close friends. There are difficult scenes in each of my historical novels. In Judith, which is based on the Biblical the Book of Judith, there is a scene dealing with the terrible cruelty of war. It was so difficult for me to write, I actually got stuck for months. I couldn’t bring myself to write it. Then I read the first Game of Thrones book, and it took four days out of my life. Two to read it, two to sulk. I decided if I was going to invest that much emotion in a book, it had better be my own! So thanks to Martin, I finished Judith.

In Under the Pomegranate Tree, the protagonist is kidnapped and abused by outlaws. And the historical novel I’m drafting now, Julian of Norwich, is about the 14th century mystic and anchoress. She lived through three rounds of Plague, and lived in a small room attached to a church for the last decades of her life. (Ironic that I have drafted it during self-isolation and Covid.). But I never include difficult scenes for the sake of shock value. My novels always move toward redemption.

GTL: What is your writing process like? Which do you favor, starting or revising?

LM: After I do my morning chores — let the dog out, eat breakfast, brush my teeth, and dress — I sit down and interview my character. I learned this technique from novelist Louise Hawes. First, I sit down with my eyes shut and nothing crossed, picture myself in a place where my character would come, and wait until she appears. Then I ask, “How do you feel? What do you want? What do you fear? What happens next?” Maybe all those questions, one at a time, or just one of them. Sometimes she answers by showing me, sometimes she tells me in words, and sometimes I feel the feeling inside myself. (I often laugh out loud or cry while I write.). Then, I write the scene the way she has shown it to me.

After lunch, I deal with editing the morning’s work and any writing business, like contacting my publisher, doing interviews, marketing, and so on. I write five or six days a week and take a day off whenever I feel the story slowing down. After I finish the rough draft, which can take one or two years, I revise, edit, and proofread. The whole process can last five years. I love starting, the purity of creation, and the thrill of discovery in research. Revision is hard work.

GTL: How has your writing process evolved?

LM: When I first started writing mysteries in my late teens, I wrote late at night, when I knew I wouldn’t get interrupted. I spewed words, thousands a day. This is when I joined Louisville Writer’s Club, and began to understand revision. Then, I went to a writers conference held at a university and signed up for an appointment with one of the authors on the panel of the conference. Unfortunately, I got assigned to a professor on the literature faculty. He shamed me for writing so much, so fast. I didn’t write anything for a year. Slowly, I got back into gear, but I wrote much slower — not because of the professor, but because I was regaining my confidence.

In my early thirties, I experienced severe abuse that made me unable to write mysteries any more. I just couldn’t cope with writing about violence as the core of my novels. After that, I fumbled around for what I wanted to write for years. I drafted a couple of romance novels, but found the tropes of the genre too restrictive. I tried my hand at picture books, but they are the most difficult thing to write — every word has to develop character and plot. I wrote a few fantasy novels for young adults, and a couple of those are on my agenda to revise and submit for publication.

I never meant to write historical novels. But those are the characters and stories that show up for me now. I had a stroke in the language center of my brain about eight years ago. In the first year of my recovery, drafting Under the Pomegranate Tree was a big part of my recovery. When I reread what I’d written a year later, I cried. One sentence a day, often barely coherent. But that writing has everything to do with my healing and my capacity for writing now. I have drafted 75,000 words during the pandemic, but self-isolation has lots to do with that too. It’s amazing what I can accomplish with zero social life.

GTL: What would you like readers to know about your forthcoming book from Pearlsong Press, Under the Pomegranate Tree?

LM: Thirty years ago, a writer friend and I sat in a coffee shop and idly hoped that, at some point in history, a young woman who was being forced into an unwanted marriage had had the wit to run away instead. When I finished Judith, I conceived of Under the Pomegranate Tree as a prequel, which is why it’s set in the ancient Middle Eastern land of Ammon in 2500 BCE. Horses play a vital part in the story, both to the protagonist, Sarah, and the plot. How she frees herself, from both her father, her captors, and the repercussions of her actions, reflects my own experiences and contemplations about them.

GTL: Thank you so much to Dr. Moïse for sharing her experiences as a writer!

Wow, I am in awe of Moise for using her writing to help recovery from a language-center stroke. Her patience and dedication are inspiring. I also like that she talks about interviewing her characters before she starts writing each day- that’s not something I do quite so often or formally, but it is a trick I’ve found handy, looking at individual characters and their motivations at different points. Otherwise, it can be so easy to get caught up in the way the plot fits together as a whole that you can forget about the little pieces while writing and end up with characters that don’t quite make sense.

LikeLike

Absolutely can happen that characters don’t fit together when we get too engrossed in plot!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know that one of my issues when I was doing more fiction writing was totally forgetting setting! It’s like my people were in some big, white void — but they sure had some funny dialogue.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The big white space sometimes happens to me too! Fortunately, setting is something a writer can color in after the first draft, when she has the bones of character and story on the page. (Give me a hot fire and a big spoon, and I can mix those metaphors!)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Have you read Peter Mendelsund’s What We See When We Read? I loved that book. It talks about how nebulous our visualizations can be while reading, and I think about it often when I’ve got staticky settings or characters in my head- your big white void reminded me of it! It’s wild what our brains will fill in or work around while reading (and writing).

LikeLike

I think I read that, but my memory has serious holes in it since my stroke, so I’m not sure.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Oh, that’s entirely understandable! I was curious about whether Melanie had read the book as well, but I didn’t make that very clear in my comment, sorry! Thanks so much for kindly taking the time to read and respond to my comments Dr. Moise, and for answering so thoughtfully to Melanie’s questions as well- as an aspiring writer it’s always so helpful and encouraging for me to see where others have succeeded before me and what’s kept them going. I loved reading about your writing journey! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

My absolute pleasure!

LikeLiked by 2 people

I haven’t read that book, but my library has it so I’m going to grab it! I also recommended it to Jackie, as she does not see pictures in her head when she reads and may enjoy this text.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A great interview, as always, Melanie. I appreciate how you want to uncover more about the woman behind the words rather than the words themselves. I always find these interviews meaningful as a result.

Dr. Leslie Moise – thank you so much for taking the time to answer Melanie’s questions. It sounds like your relationship with writing, and the journey it has both taken you on and been a part of, is highly complex. I appreciate how clearly you’ve laid out your experiences for us. That takes courage! When you had your language-center stroke, what inspired you to start writing again? That must have been so agonizing, trying to put your story to words when you lost them…

LikeLike

Thank you for your good question. It never occurred to me not to write; writing is at (is!) the core of my being. Even though writing that one sentence a day exhausted me, I wanted to do it with every fiber of my being.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My goal is to get an interview that is both interesting in content and can be enjoyed by folks who haven’t read the author’s book. I always find book-focused interviews frustrating myself because if I haven’t read the text, the interview means nothing to me.

LikeLike

I had a recent online conversation with someone who doesn’t read book reviews because too many reviews are really just summaries. You do an excellent job of providing context without giving away content.

LikeLike

Thanks, Leslie! I have two masters in creative writing degrees, so I’m always reading with a craft perspective more so than sheer enjoyment or relation to characters and setting. I can see what moves an author made/tried to make, and that tends to be where my review head.

I’m with you and your writer friends. A lot of reviews are just summary and then a one or two sentence declarative of “I liked it!” or “I didn’t like it!” Mostly, I only follow book bloggers who avoid such silliness.

LikeLike

Great interview! The topics and historical women she explores sound really interesting.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much. I do find spending time with the women from other times and places very fascinating!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Karissa, do you like reading historical fiction? It’s not one that I associate with your book blog, but I have learned that some folks really like to read certain genres that they don’t review for whatever reason.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I read some historical fiction though I guess not a lot. I was noticing that she has at least a couple of books focusing on women who are Biblical or religious figures and I do like reading fiction that explores those themes, especially with a focus on women.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I tend to write about characters and topics that keep bothering me for years–sometimes decades!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow, Leslie’s story is so impressive! It really is a testament to her inner strength, it seems like she’s overcome so much, yet writing always is, and continues to be a big part of her life. Inspirational really-you always come back to what you love, and are meant to do.

LikeLike

Thanks! I actually believe the stroke helped me focus on what really matters to me. Before it, I distracted myself with activities that pulled my focus away from writing, although I now see that they also fed my life experience.

LikeLiked by 3 people

I’m reading her memoir, Love is the Thread, right now and am loving the way each memory catches something beautiful. The way she and her friend are growing out of hardship (for Moise a toxic relationship and for her friend bipolar disorder).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you. I originally was writing what became LITT for Kristine’s friends. It grew into a book.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The idea of fleshing out the story of mythic and legendary heroines appeals to me too; I’m always interested in the idea of the story that hasn’t yet been told, the story that hasn’t been preserved. Also, love stories of determined recovery and the way that a personal dedication to small steps can restore capacity-wonderful.

LikeLike

That’s an interesting note about preservation. I hadn’t thought of fictionalizing history as a method of preservation, but you’re right. Even if someone reads a novel about a historical person and then seeks out more information, that’s a way to create buzz.

LikeLike

I love exploring other times and lives different from our own, and discovering the similarities hidden in those differences.

LikeLiked by 1 person