Stephanie Klein’s memoir Moose is a compilation of the year she spent going to fat camp, a time which eventually led to her working as a counselor there. The book opens with her standing on a scale in the OBGYN office. Although she is pregnant with twins, Klein doesn’t want to gain weight, so she is surprised as the nurse makes clear the harm she could do to her unborn children if she continues to diet while pregnant. “Fifty pounds,” the nurse says. Klein has to gain fifty pounds for the sake of her children, and to eat whether she’s hungry or not. Panic sets in.

This is when we jump back to Klein’s childhood. Her mother, the chronic dieter who is already thin but vocally hates her body. The father, who eats “meals for a man” rather than the diet foods his wife and two daughters eat at dinner, who reminds his daughter she is fat and makes fun of her. The little sister, who is physically active and not considered fat, but sent to fat camp with Klein so they aren’t separated and then develops disordered eating. The boy at school who calls “Moose” down the halls at Klein. The group therapy diet meetings that start in elementary school.

In her introduction, Klein is clear:

Moose isn’t a book about accepting yourself as you are, embracing life as a fat girl. It’s not pro-fat, peppered with tips for learning to love your cellulite. It’s not about overcoming eating disorders.

Although I chose this book in the hopes that it was exactly what Klein straight-away said it is not, I kept reading, hoping to understand the mindset of someone who hates fat people because she hates herself — both when she’s fat and underfed. Moose definitely will not go on my recommendation list for reading compassionate portrayals of fat women; however, I’m still glad I read it.

For instance, Klein can write the truths about dieting, even though she can’t apply them to herself. At a fat camp called Yanisin, she notes that the same campers return yearly, always fatter than the previous summer. Camp life is so regimented and routine that it can’t be replicated in real life. Counselors guard food stores and go through campers belongings looking for contraband. If you’ve seen the classic film Heavyweights and then read Moose, you will definitely see parallels.

She also speaks the truth about prejudice, even among fat kids at fat camp. At Yanisin there exists a hierarchy: small-fat and medium-fat kids hate the very-fat, for example. One boy, who is fat enough that the counselors weigh him at the local truck stop instead of camp scales, is in foster care. Rather than feeling compassion for him, Klein writes that she didn’t believe he deserved a family because he was too fat and couldn’t be loved. As hard as that is to read, it emphasizes the insidious nature of hating fat people.

And even though Yanisin proclaims that it’s helping children learn healthy habits and competency in skilled sports (rather than running constantly for basketball, they gain confidence in their dribbling and shooting skills), it’s a place that creates eating disorders. There, Klein learns about binging and purging, then proceeds to teach her fellow campers. Diet tricks are repeated like the Ten Commandments, although they always begin, “I read somewhere that if you. . .” and have no basis in actual nutrition or science. Klein goes so far with random diet tricks when she’s a counselor to a group of eight-year-old girls at Yanisin that her division leader has to tell Klein to stop.

All of this is to say that I appreciate how Stephanie Klein doesn’t pave a smooth road for readers who want some lesson at the end. She’s honest in her acknowledgement that her thinking is utterly messed up, despite evidence that she’s harming herself, other children, and her unborn babies. Disordered eating is a disease that requires therapy and kindness, and it doesn’t seem in Moose that Klein has experienced either (the diet therapist doesn’t count). She even hires a doctor (who operates out of a house??) whom she literally pays to tell her what a piece of garbage, reminding her she has “a ways to go” at size four. The hatred and abuse is hard to read, but the more the memoir went on, the more I understood how hated of fat people proliferates. How it spreads so easily, even among fat people.

A shining star does exist, though, and it’s not in Klein. The author’s fat camp best friend and bunkmate, is Kate, who sees through Yanisin, finds ways to work the system, and is full of the weirdest, funniest quips I’ve read in a memoir, like “Now get ready, darlin’; you’re about to be fat-flocked quicker than two jiggles of a jackrabbit’s balls.” Who is this lovely, weird tween?? She’s the one who tells Klein, “I’m not here [at Yanisin] to be saved, either. Shit, I was born fat. . . . My whole family is fat, and as much as I diet, I always come back to this.” Klein, unfortunately, takes Kate’s speech as resignation to being miserable. But Kate isn’t miserable. She’s a hoot, and I would love to have had a friend like her when I was thirteen.

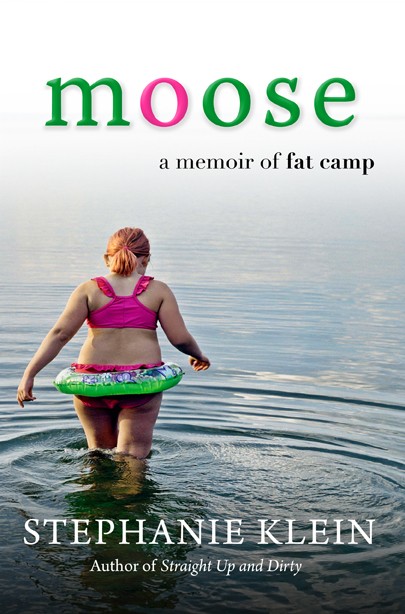

Moose interweaves fat camp (click for image of author at camp), public school, flashbacks of traumatic family moments, and Klein’s future as a mother in a successful effort to show how the author became the weight-obsessed person she is. It’s worth the read to gain understanding, though it can be upsetting for the humiliation, violence, and disordered eating this memoir contains.

I read a fair bit of the excerpt. Klein is full on about the desirability of being thin, despite her love of eating. Do you think she hates her teenage self? Her parents seem to have done their best to persuade her to (or at least, that’s how she now sees them). No one is very reliable about their teen years, perhaps Kate’s in there because at some level Klein understands Kate was right to accept herself.

LikeLike

Klein said she hated herself as a teen, and that she couldn’t fathom how Kate couldn’t hate herself. The fact that Klein includes that introduction stating this is not a fat-positive book, nor is it about self-acceptance, tells me that she just wanted to document what it was like during that time of her life so people could see. She’s not meant to be an inspiration. Based on the photos on her blog, it looks like she’s still obsessed with thinness, though possibly kinder to herself.

LikeLike

I agree that this sounds like an important book, but even reading your review made me a bit twitchy and anxious, so I’ll think I’ll be skipping this one! The idea of eight year olds at fat camp horrifies me. I mean, the whole fat camp idea is distressing in the first place, but for a literal child to be sent to one is incredibly distressing.

However, I love that Kate accepted that her family was just a fat family and that’s the way it is. Part of what has helped me to be more okay with the way I look is seeing a photo of my maternal grandma when she was in her late twenties. She was a district nurse cycling many, many miles a day – during rationing! – and yet I look very much like her (except that she was short and dark-haired). It was at that point that I really twigged that I was trying unsuccessfully to fight genetics, and was just making myself tired in the process.

LikeLike

I love that you have that photo and can see yourself in it. Also, what a great story about a bicycling nurse. On a number of occasions I’ve landed on an internet thread in which people tell when they were first put on a diet. Eight seems to be a common age.

LikeLike

It never occurred to me that fat camp was a place you might grow up and return to as a counsellor. I feel like books like this are often told as inspirational – either the author loses weight or embraces their body – but that doesn’t sound like the case here.

LikeLike

Truly. She got into her adulthood a bit, and it sounded like when she was happy and eating with a boyfriend, she gained weight. He left her and then she got skinny again. Back and forth. It wasn’t praising weight loss or about self-acceptance.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Was there any sense of a conclusion? Does she change from the beginning to the end of the book?

LikeLike

She had the twins and discussed trying to teach them health eating rather than random diet tips she told the eight-year-old campers when she was a counselor. It’s also not clear to me if the husband she divorced is the one who fathered the twins, or a guy before this father. So, there’s not really a “the end” to this story, more of an acknowledgement of how messed up her thoughts about eating are, and how forcing children to diet is bad. However, I also got the vibe that she would be one of those healthy eating people until she put on ten pounds and had a meltdown kind of people. She suggests as much.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It sounds really different from how these types of books usually go. On the one hand, I’m kind of left wondering what the point of the book is but on the other, it’s her life and she doesn’t owe anybody a revelation and it’s probably a realistic portrayal for a lot of people. I’m surprised she was told to gain so much weight when she was pregnant though.

LikeLike

I have no clue why women are supposed to gain weight while pregnant, other than baby weight. 50 pounds for twins and told to eat even when not hungry. Maybe they’re sucking that much nutrition out of her? I don’t know. She was dieting while pregnant, so I doubt she was eating enough for her own body. Maybe the lady meant 50 pounds is normal to gain? At first, I was picturing the author with a pregnant belly and told to gain 50 pounds of fat. Again, no clue how it works, which means I’m going to head over to Google and find out.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Okay, I read this: “Weight gain is especially important between weeks 20 to 24 of pregnancy. If a mother of twins gains 24 pounds by the 24th week of pregnancy, she reduces her chance of preterm labor. Early weight gain is also vital for the development of the placenta, which aids in the passing of nutrients to the babies.”

LikeLike

Usually, the amount you’re told to gain in pregnancy includes everything – baby, placenta, everything – so it makes sense that someone pregnant with twins would gain more. (Average weight gain is more like 25 – 30 pounds.) But mostly that’s weight that gains itself! That a medical professional would stress she gain that much weight makes me think she was underweight to begin with or there were other complications.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This sounds too difficult for me to read, as I have a friend living with a Severe Enduring Eating Disorder and I find it hard to read about that stuff. But I’m glad she’s set out these important truths.

LikeLike

It WAS a hard read, and I can see why some readers would totally avoid it for their own protection.

LikeLike

Whoo boy!

LikeLike

You are forever in my heart 😂 Every time you write this after I told you this is an acceptable comment at GTL, it makes me just so happy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This sounds like a really intense book. The idea of trying to change your kids weight and body size is hopefully changing-I follow this woman on insta who advocates for kids eating healtheir and lots of veggies, and she is constantly asked how to change kids body sizes, as in, how do I make my kid bigger or smaller? And she constantly replies and reiterates that as parents, it’s not our job to change our kids body size, it’s our job to teach our kids how to eat healthy and why eating healthy is important. Now that’s a mantra I can get behind!

LikeLike

Yes! I half-wonder if we need some sort of “normalize eating” campaign. Even as an adult I still hear people constantly shaming themselves for eat *anything.* I’m also a big proponent of eating variety. I do actually picture Michelle Obama’s healthy food plate thing (https://tinyurl.com/yxpmzd5h) from when she was in the White House. It makes loads more sense than the food pyramid, which suggests I should keep a spreadsheet on me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Gawd, Michelle Obama we miss you!!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great review. I like that the author doesn’t seem to pull any punches, showing readers through her own experience how toxicity toward fatness can be internalized and from there can grow and spread further. But I think for me there would have to be some sort of upside or learning advice to go along with the negative experience in the book, some level of self-reflection and change, even if it’s something the author continues to struggle with by the end of the book. It sounds like there’s not much direction here, just a recounting of woes that aren’t leading toward any conclusion? I can see how reading the author’s thought process might be helpful in understanding another perspective, but I’m left wondering if this author couldn’t have provided a little more takeaway.

LikeLike

The memoir is book-ended by her experiences being pregnant with twins and then the mother of children whom she doesn’t want to mess up by filling their heads with dieting advice and angst. It seems like she’s really trying, but I do know several Goodreads reviewers commented that she should just put herself in therapy, which they may have decided to write based on the small progress at the end of Moose.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It makes me so sad to think that parents make their kids feel bad for the way they look. It sounds like Klein didn’t really have a chance.

LikeLike

Naomi! 😮

LikeLike

Hi! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know it’s only tangentially related, but this reminds me of the storyline in This Is Us (do you watch that show?) about a character whose weight takes on a different focus in the context of pregnancy (I’m being super vague here because this isn’t a storyline that arises early in the show, so if you do watch, but aren’t caught up, I don’t want to spoil anything–there are multiple timelines at play, so hopefully this isn’t spoilery already).

LikeLike

I’ve heard of This Is Us but not seen it. Tangential comments are typically where I land myself. Sometimes, I don’t have much to say about someone’s post, but I want to talk to them!

LikeLike