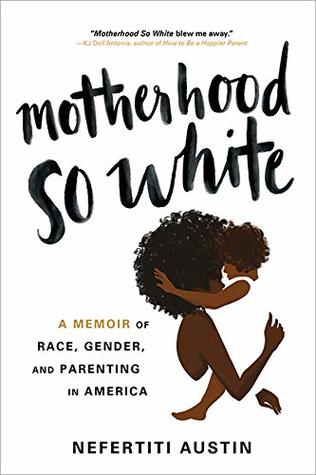

In a country that surely has too many parenting books and blogs with varying advice, Nefertiti Austin discovered that none applied to a single Black woman looking to adopt a Black boy. There were elements she could take from the two-parent white experience, but she still had questions. How do you raise a Black boy in America? How do you create a team of people around a child so he has a community? Does every child need a mother and father? Because Austin knew no one like her, she wrote a memoir about growing up in a “Black adoption,” taking courses on fostering and adopting children to earn her license, and building a family on her own through the power of choice. Thankfully, we now have Motherhood So White: A Memoir of Race, Gender, and Parenting in America.

Because her parents couldn’t choose parenting, Nefertiti Austin and her brother were raised by their grandparents in what she explains is a “Black adoption.” Done for hundreds of years, traced back to Africa, a Black adoption doesn’t take place on paper. She writes, “The family taking in the child needed a connection with that child, even a tenuous one.” This moment of her off-paper adoption connects to the way her family feels about her adopting a stranger’s child. Why would she do such a white people thing, they wondered.

Let me be clear: in the United States, adoption stories we see in life and the media are always a white man and woman, often strongly Christian, adopting children from countries populated by brown people, like China. Austin changed my mind about what adoption can look like by sharing her experience:

Foster mother in Los Angeles County tended to be Black women, and the media reinforced the image of the scheming Black welfare mother who preyed on poor and neglected children to get out of real work.

The author’s story highlights a few important things: 1) that black women want to care for unknown children in their communities, 2) that the media won’t give them a chance, and 3) the media also does not see childcare as “real work,” a delusion that any parent can tell you is dangerously inaccurate.

Further disconnecting potential parents from children in need is false perceptions of a child’s origin story. Austin writes about families unwilling to foster or adopt Black boys because they are viewed as naturally rambunctious and problematic. There is also the fear of “crack babies,” used to describe Black children regardless of circumstance. Furthermore, the parenting classes Austin takes to become licensed to foster teaches her that children who are born to mothers who used crack will detox yet be stigmatized, whereas a child born to a mother who consumed alcohol will have life-long developmental issues yet not be ostracized like “crack babies.” Deep down, readers of this blog know that racism and stereotyping are wrong, but Austin airs everyone’s fears and writes through them in a straightforward fashion.

I’ve seen a proliferation of spaces where white people ask Black people questions without fear of judgment. I appreciated Emmanuel Acho’s appearance on CBS This Morning recently to talk about his video, “Uncomfortable Conversations with a Black Man.” Similarly, Nefertiti Austin discusses naming black children, getting to uncomfortable truths, such as the way her foster son, named Kemarye, would struggle with employment despite his credentials, attitude, and family traditions. When she officially adopts him, she changes his legal name to August, after the prolific playwright August Wilson.

If you’re a mom or a mom supporter, you’ll recognize where Austin goes wrong in motherhood in small ways that could be avoided if we were pro-parents in the U.S. For instance, she feels like she’s not allowed to ever complain because she very intentionally chose motherhood. Like the Pixar movie Inside Out teaches us, if we aren’t sad or angry, no one around us is alerted to our need for assistance. Despite not being pregnant or giving birth, she’s physically exhausted in a way she hadn’t imagined possible, and I believe it’s easy for mothers with healthy bodies and financial security to feel the same way. Although Austin’s journey is different, all parents and people who support parents will connect with her story.

Beyond sharing her story — and this part completely warmed my heart — Austin includes an afterward in which she interviews several other Black women who adopted. This final special touch hits home that her journey is not unique, it’s just untold. There are important lessons in this final section, such as “love does not conquer all.” Austin explains, “And should you decide to adopt transracially. . . .You must do your homework and become culturally competent about your child’s heritage.”

Carla, a woman the author interviewed, has great advice for all parents, but especially those who adopted: “Advocate for your child at every turn and with everyone, including schools, doctors, family members, and so on.” Carla further notes that before she adopted, she found “a pediatrician, a pediatric dentist, an ophthalmologist (all Black men), and a babysitter. . .” The advice that adoptive mothers, especially those raising Black children, have is priceless for all parents because they’ve learned to craft a community, a village, really around an adopted child.

Motherhood So White is a beautiful, gorgeous, important memoir.

Interesting look into something I never really think about.

x The Captain

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great review of what sounds like such an interesting book. I was particularly struck by the point that adoption narratives are always about white families adopting children of colour.

LikeLike

In the U.S., the only experience I can think of that I’ve see are white people adopting children from China. There was a big trend about ten years ago to get children from China, typically girls, though I don’t want what specifically caused that trend. Although I know people the world over have children who need families, I think it’s especially important to adopt children from within your own community so you’re not completely transplanting them to a “new life.” I might be wrong, but that sort of feels like pretending that child didn’t have a life before meeting their adopted parent/s.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Don’t quote me on this, but I wonder if the push to adopt Chinese girls had to do with the baby limit in China, and parents’ desire to have boy children, thus leaving many girls available for adoption elsewhere… It’s been a long time since I heard about that so I might be misinformed or remembering it wrong. But often in film at least I see white couples adopting children of color. One of the first times I saw it was in Grey’s Anatomy probably about 10 years ago, and after that it has seemed to pop up often. I don’t pay a lot of attention to real life adoption trends or read about them so I’m not sure if there’s a real correlation or if that’s just a TV trend!

LikeLike

I definitely thought there was a connection between Americans adopting Chinese children and the One Child Policy, which has since “relaxed” into a two child policy. Girls were becoming so rare in China that an entire generation of young men couldn’t find partners, and people were resorting to kidnapping little girls to keep and raise alongside their sons so they could get married one day.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah, yeah, that fits with what I’ve heard, though it’s been a while since I’ve brushed up on the details. I didn’t realize it had become such a problem that kidnapping to ensure marriage was involved! I’m very relieved to learn that the policy has been relaxed somewhat, at least.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I saw this on a list of books the Stacks Podcast put together, of books about Black experiences by Black authors. i ordered it right away but apparently I don’t get a copy until September! Must be a Canadian thing. I was excited to read it before but after reading your beautiful review, I can’t wait to get my hands on this one!

LikeLike

I’m so glad! I’m not sure about Canadian copies. It came out in September 2019, so maybe there is a one-year difference. Thank you for your compliments 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

That looks amazing. I am going to wait till September to look for the paperback as the hardback is expensive here but I don’t want an ebook of it. I think the narrative here in the UK is also of white couples adopting white children (but with “issues”) as well so that’s very interesting.

LikeLike

What do you mean by issues? I know that here a lot of white families frequently adopt children from other countries, and you don’t hear much about people adopting children from their own communities, like Austin and the women in her training group did.

LikeLike

I’m sorry, I was bring mealy mouthed there. Most children up for adoption here have a disability, development disorder or severe emotional problems or are in sibling groups. And you’re not encouraged to adopt outside your ethnic group within the country either.

LikeLike

Ah, yes! I see what you mean. I wasn’t sure if you meant the parents were having issues adopting because they’re single, not super wealthy, the “wrong” race, etc., or if the children were ones with issues, bringing unique challenges, such as physical or mental disabilities, help with socialization and trust, emotional issues, etc. Then there are issues that can arise from birth parents who keep popping up and may be disruptive or unreliable (and I’m always crossing my fingers that I hear stories about good relationships between birth and foster/adoptive parents.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lovely review – it sounds like a very good book and so needed.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This books sounds great! I’m down for any book that flips a problematic stereotype on its head, but this one sounds especially compelling and necessary. I want to read this, as well as I Am Not Your Baby Mother by Candice Brathwaite, which focuses on how prenatal advertisements and motherhood in general is portrayed as white in the UK.

LikeLike

I checked out that Brathwaite book and added it to my list. What I’m realizing, and I feel dumb admitting to this, is that we almost NEVER listen to black mothers, especially women who have been mothers for a while. I’ve read a number of memoirs in which black women complain about their mother’s behaviors and choices, but what’s going on with the mom that she’s like that? We never hear from her.

LikeLike

You are so right. There are a lot of narratives out there about Black mothers being harsh and “bad” parents, but if there’s any truth in it, it’s probably because society is failing Black women.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The narrative in Australia runs from the opposite direction – the stealing of Aboriginal babies who had white fathers from their mothers and their adoption by white families to be brought up white. Those children were largely brought up divorced from any contact with their Aboriginal heritage and often with little or no hope of ever regaining contact with their birth mother and siblings.

Yes it is outlawed now, but Aboriginal babies are still taken from their parents at a much greater rate than white babies and put into care, which generally means being given to foster parents, sometimes within the Aboriginal community but I think more often not.

I read an interesting US article yesterday about ‘putting children into care’ being weaponised as part of the armory in ‘the war on drugs’, ie. drug users are further punished by losing their children. This of course applies much more to Black parents than to White, in the US and in Australia.

LikeLike

I’ve also heard about how foster care and adoption can be big business, if the adoptive or foster parents go through a for-profit agency, which may give them a better experience because the agency has more money and resources from charging people so much, but that also means that wealthy or well-to-do families are more likely to adopt, and there is little motivation for reuniting children with their parents because that child is an asset.

LikeLike

What a much-needed book! It sounds like she has great advice that can benefit all parents, but you’re right in pointing out the lack of resources for adopting parents. The foster care system everywhere, in my opinion is broken. We don’t invest enough money in it as a society, which is ludicrous considering it has direct consequences on our future. A friend of mine who wants to foster children (and has one of her own) wasn’t able to do it financially because both her and her husband work, and they couldn’t afford the childcare costs to send a second child to daycare.Arguably, having both parents working (reasonable hours) is better for a child because it helps them socialize in daycare, and gets them out of the house consistently. And really, that’s just ONE of the problems. Don’t get me started on people claiming parenting isn’t real work, it’s the most difficult job in the world!

LikeLike

I totally think parenting is real work, and that’s part of why parents who work 12-hour days make me grumpy: they have another job at home, and who is doing it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I see your point, and the answer varies based on income level unfortunately 😦 I keep thinking of all the kids whose parents have no choice but to go to work during the pandemic (grocery clerks, janitors, etc) but who can’t afford child care, and with schools closed many kids are probably just…at home alone.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This sounds fascinating – I’d never really thought about the stories we hear about adoption and fostering. A lot of the stories I have heard recently have come out of Home for Good – people from my church were involved in setting up this charity but it’s run by Krish Kandiah, who describes himself as “Indian (mostly)”, so I think the stories that they tell about fostering and adoption are intentionally more representative. Before then, now that your review has made me think about it, I have mostly heard about white families adopting white children.

LikeLike

I read and reviewed a book called The Family Nobody Wanted, and it was about a couple who adopted many children from all different backgrounds during a time when that was NOT done, and there were ostracized at times. People wanted to see white couples adopt white babies. However, the narrative shifted at some point to see more like what Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie did: adopt children from around the globe who are not white. I also think that narrative is problematic, as it pulls children out of their communities and suggests whatever the white parents do is “better” than where the child came from. This was a great book, and another reader commented about an adoption book written by a British woman that I want to check out.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This sounds fantastic! Lots to think about when it comes to our perception of parenting and how that relates to race. I can relate to feeling like I can’t complain about the hard parts of parenthood because I chose to have my kids and I can believe that that feeling would only be stronger for adoptive parents.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is a great review! The fact that adoptions portrayed in media and elsewhere are often white two-parent parent families is not something that I had particularly thought about before (that’s my privilege showing, I’m sure), but I can see how having that image as the “norm” could make it harder for POC to adopt, though they should have just as much right and opportunity to do so! I’m glad books are now being written on this specific topic, something that focuses both on the process of adopting as a POC and also as raising a child in a place where he will be in a minority group. Both very important discussions to have available in the public sphere. Thanks for putting this one on my radar!

LikeLike

Austin makes so many great moves in her writing to make Motherhood So White this wonderful blend of memoir, educational material, and guidebook. I read it pretty quickly because I was so invested. When she wrote that the classroom for people to become licensed to foster was a room full of black women, I was surprised, which shows just how media really does affect the way we see things.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I read this review a few days ago and was too upset to respond then. I’ve calmed down a bit now, though…

Your review really struck me! Partially because of how you write (soooo good) but also because of the content in Motherhood So White. I’m upset with myself for never seeing this, though I’m certain I’ve *been* seeing it my whole life. Thank you for sharing a review of this book with us. We needed to hear this.

Thinking back through all the times media exposed me to fostering (Angels in the Outfield being the most obvious), black women are never present unless they are a villain. Even in Angels in the Outfield the foster mother is a white, Irish woman (and, stereotypes imply Irish women should have HUGE broods of children under foot all the time) and when Danny Glover adopts the boys it’s only because he’s a *wealthy* black man that he can do so. Ugh. I’m so frustrated right now. I want to shout down this unconscious bias people have from the rooftops!

I’ve definitely added this to my TBR. Thank you again for sharing!

LikeLike

I’m sorry you were upset. I think seeing something for the first time that was always there is incredibly hard. When I was growing up in central Michigan, I was convinced the whole city only had one homeless person, and that’s because she was highly visible and notorious. But my hometown has a large state university, and when I started teaching, the textbooks I selected had essays about students who write down an address as their home location, but are actually homeless, living in their cars or camping in nearby woods, and then showering and getting ready at the campus work out center and studying or hanging out in the library. There HAD to be homeless students at my college, but I never thought of them until I read about it, and then I realized it was so obvious. I later worked at a camp ground and discovered lots of people without permanent homes will camp all summer for the free electricity, sewage, and showers.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I remember coming to that realization at my first teaching job. I was teaching middle school instrumental music. This was when I realized that a much higher percentage than I expected (18% of the student body) was homeless or transient. The school I worked in was only a few years old, had all the fancy tech, and all sorts of stuff only a high property tax bracket could have brought us. I just didn’t realize until mid my first year that this district was half nouveau riche and half single moms in subsidized housing.

So yeah. I can relate to that shock. Why do we hide these things in plain sight? Or, probably more accurately, why don’t they get called out instead of thrown to the side and ignored? #StillAngry

LikeLike

Was this a public school?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yup. I’ve only taught in public schools.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s not until you mentioned it here that I realized most adoption stories really do feature a white, heterosexual, Christian couple. Over here we have something similar to ‘Black adoption’ – many children whose parents cannot or will not take care of them are taken care of by the extended family instead, perhaps the grandparents or an aunt. Coming from a similar kind of notion of adoption, I can imagine how strange it might be for others to hear about her adopting a stranger’s child. But I’m glad the author was able to talk about her experiences and to raise awareness on being a POC adopting another POC. Motherhood isn’t inherently appealing to me as a topic but this intersection of motherhood and race seems very interesting.

LikeLike

I don’t have children, nor have I ever wanted them, which makes some people think I don’t care about children. Nothing could be further from the truth. I care about their welfare and safety, I always vote to raise how much we pay on taxes that go to the school or busing or lunches, and I try to pay attention to the foster system in case anything ends up on a ballot about foster care. This was a great book that made me think about larger communities even more so than motherhood.

LikeLiked by 1 person

If only we were pro-parents and families in the United States! The ways we fail families are especially clear during the pandemic. This sounds like such an interesting and important memoir.

LikeLike

You’re right about the pandemic. People struggling to be parent, provider, and teacher to their children, plus maybe also spouse, care giver, etc. While I’m excited that schools are talking about having kids come fewer days per week so teachers can instruct about 50% of the class at a time, I wonder how that works with childcare on those days when kids too little to stay home alone have parents who work.

LikeLike