Welcome to Week #3 of A Month of Reading Flannery O’Connor. I can see how this writer is developing from a novice in the creative writing program to a woman with a rigorous writing schedule living on her mother’s farm in Georgia. The shift: the people are more vivid, her intentions are more nuanced, and her characters’ motivations are more thought-provoking.

THIS WEEK’S STORIES:

- A Circle in the Fire

- The Displaced Person

- A Temple of the Holy Ghost

- The Artificial Nigger

- Good Country People

- You Can’t Be Any Poorer Than Dead

- Greenleaf

SOME CONTEXT:

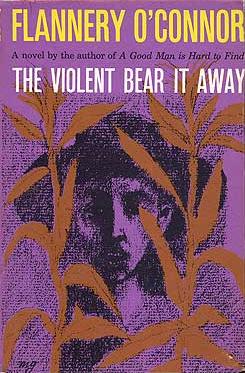

Most of these stories were published in the short story collection A Good Man is Hard to Find (1955), same as last week. We do get into some of the stories from O’Connor’s second collection, Everything that Rises Must Converge (1965). The second short story collection came out after her second novel, The Violent Bear It Away (1960), was published. Long before I started Grab the Lapels I read O’Connor’s second novel and was intrigued by the characters; I got to meet them again in one of this week’s stories.

Another bit of context that potentially makes a big difference: beginning in 1950, the author was diagnosed with lupus, and though she occasionally traveled to give lectures, she was largely home-bound in Milledgeville, Georgia, on a farm called Andalusia with her mother and hired help, people about which her mother frequently talked/complained.

In addition, O’Connor’s good friends Robert and Sally Fitzgerald, with whom she lived in New York for two years, kept having children. In letters addressed to the Fitzgerald couple, O’Connor frequently marveled at how many offspring one pair could produce and referred to the youth not coldly, but not as fondly as you might expect (in her letters, I don’t recall seeing the children named, nor praised individually. It was more like, “Wow, you had another one?”).

EXAMINING THE third SEVEN STORIES:

“A Circle in the Fire” ( published 1954 in Kenyon Review and 1955 in A Good Man collection) is one of those stories that raise my blood pressure. I have a strong sense of right and wrong, even if I’m being inflexible. When children do not see adults as authority, it stirs a deep fear in me, and I want the offenders corrected immediately. Mrs. Cope, a woman who cannot, well, cope, believes there is always something to be thankful for. I’m guessing God sent those three heathen boys to test her faith. “A Circle in the Fire” struck me as a great study during a pandemic: people compare the ways in which they suffer due to COVID-19, but someone will always outdo them. Bored? At least your not hungry. Hungry? At least you have your house. Homeless? At least you don’t have COVID-19. Have COVID-19 and recovered? At least you aren’t dead. Mrs. Pritchard seems to understand that comparing suffering is worthless because denying a person’s ills denies them their humanity. Thus, when Mrs. Cope is tortured by the terrible trio, Mrs. Pritchard doesn’t care; the farm isn’t hers, so it’s not personal to her, but her rotting teeth are.

“The Displaced Person” (published 1954 in Sewanee Review and 1955 in A Good Man collection) also emphasizes being grateful. O’Connor acknowledges the Holocaust in this story (and the previous), but Mrs. McIntre doesn’t seem to grasp what the camps in Europe are. Mrs. Shortley has seen the same famous images of mass graves of emaciated bodies that we have today. There’s a trend this week of examining women who own farms and struggle to keep the help. Both dialogue and characterization are improved in this story from previous weeks. There’s also a shift to narrators using the word “Negro” while characters still use the more offensive racial slur, suggesting O’Connor was changing her mind a bit about race, though her characters are ignorant. Yet, Mrs. McIntyre acknowledges both black and white farm hands can be greedy. In a test of faith, the displaced person in this story may be Jesus in disguise to test Christians, or the sent from the devil. I appreciate the way this story is still relevant when thinking about how we “other” and then distrust people unlike ourselves because it is more convenient.

“A Temple of the Holy Ghost” (published 1954 in Harper’s Bazaar and 1955 in A Good Man collection) is when I realized we’ve shifted to examining children, typically around twelve, as outsiders. This story makes a joke of two airheads laughing that their Catholic school teachers reminded them that their bodies are temples for God, so treat them as such. Yet when the circus “freak” who is both male and female says they are born how God made them, it is religious leaders who protest the circus. A brief story of hypocrisy made me wonder how liberal-minded O’Connor was about differences in bodies.

“The Artificial Nigger” (1955 in Kenyon Review and 1955 in A Good Man collection) is such a poorly named story, in my opinion, because it draws attention to itself for the crass name, yet the story doesn’t earn that name. It isn’t until we see the minstrel statue, popular in the southern states at the time, that the title makes sense. Instead, we follow a grandfather with admirable attributes listed in the beginning of the story, including caring for a grandson after his daughter died. But he can’t see his own sins, including denying he knows his grandson when confronted by police. The story shifts, with the grandfather being described as childlike and the boy as ancient. Throughout the trip to the city, I felt I was reading Dante’s Inferno, and the deeper into the city, especially the black neighborhoods, the closer to Hell the old man felt. Why does the boy acknowledge at the end that he’s only been to the city once, when before he claimed it was twice (he was told he was born there but he wasn’t)? I wondered if being born in the city (Hell) is symbolic of being born in sin. And what is the significance of that statue?

“Good Country People” (published 1955 in Harper’s Bazaar and 1955 in A Good Man collection) is another famous Flannery O’Connor story because people just hadn’t read about someone stealing a wooden leg before. Here, the “child” of the story is a 32-year-old woman with a PhD in philosophy who doesn’t leave her house because she’s told she has a weak heart. I connected this to O’Connor staying with her own mother, perhaps feeling like a child, because she had lupus and her bones began to soften, causing her to walk with crutches. The story focuses on “nothing” — scientists want to know nothing about nothing. Joy/Hulga believes in nothing (faith-wise). The Bible salesman suggests he’s smarter than she because he was born believing in nothing, meaning he was years ahead of her discovery. The Freeman daughters are a foil for Joy/Hulga, because they date and have relationships whereas our main character wears stained clothes, changes her name to make it ugly, and has never been kissed. When the salesman says her leg is special, Hulga is seen for the first time, making her trust. Does she want to be unique, known for her differences and not the similarities to other girls, causing her to deny any beauty? And what does it mean that he collections artificial body parts from women?

“You Can’t Be Any Poorer Than Dead” (published in 1955 in New World Writing and then as a chapter in the novel The Violent Bear it Away) is the first chapter of O’Connor’s second novel, meaning it has better context than some of the excerpts from Wise Blood. The opening sentence captures the type of writing I associate with O’Connor:

Francis Marion Tarwater’s uncle had been dead for only half a day when the boy got too drunk to finish digging his grave and a Negro named Buford Munson, who had come to get a jug filled, had to finish it and drag the body from the breakfast table where it was still sitting and bury it in a decent and Christian way, with the sign of its Saviour at the head of the grave and enough dirt on top to keep the dogs from digging it up.

Here, we get decency, faith, some dark humor, and that head-shaking last bit if imagery. What a wild first chapter: an old man living a mile from any foot path off of any road kidnaps a boy after he feels betrayed when he stays with his liberal schoolteacher nephew for three months and discovers the nephew was studying him and wrote about it. Rayber, the nephew, is possibly the same liberal teacher from “The Barber.” Again, we get a debate about religion vs. secularism. Do we owe the Christian dead their wishes? Without a cross, the old man believes he won’t be found on Judgement Day. But a ten-feet deep hole is a physical challenge, and the modern trend of cremation would be easier. The child splits into two people, the person he knew with the old man and a “stranger,” a side of himself he’s not met before, pointing out what is now obvious to him: he’s likely been used. During his ride to town with a salesman, he’s told people only matter when they’re alive, and thank God when they’re dead because it’s one less person to keep track of. This is a novel I may need to re-read.

“Greenleaf” (published 1956 in Kenyon Review and 1965 her collection Everything that Rises Must Converge) is about more no-account hired farm hands! There are a few surprises: Mrs. May is Christian but “of course” she doesn’t believe any of it. How do we interpret this knowing what we do about O’Connor’s profound Catholic faith? Is she pointing out those who profess their faith but do not act on it? Secondly, I was surprised that no other character feels that Mrs. May is wronged by a bull destroying her property and interfering in costly ways with her farm. Breeding schedules are important because time, special preparation, and even a vet may be needed during birthing season. The bull will mess this up. Even the “children” (again, people in their 30s) are against Mrs. May. Have her sons decided not to inherit the farm she’s clearly maintaining to leave to them, but haven’t told her? They continue to live there anyway. Wesley menacingly says, “I wouldn’t milk a cow to save your soul from hell.” Yikes! I see a woman who feels her sons should be grateful, but they don’t agree. Then again, where does this animosity come from? Do the other characters “see” Mrs. May’s false beliefs and abandon her for it? On the surface, I wanted justice for this woman who was being menaced, but I’m sure O’Connor’s telling me something else when that bull gores the old lady.

NEXT WEEK:

May 22nd-28th:

- A View of the Woods

- The Enduring Chill

- The Comforts of Home

- Everything That Rises Must Converge

- The Partridge Festival

- The Lame Shall Enter First

- Why Do the Heathen Rage?

QUESTIONS

My main question is if anyone else noticed the presence of a child, either literal or adult but referred to as “child,” that seems wiser than the adults? If O’Connor was somewhat dismissive of her friends’ children, why might she give her fictional children more wisdom and agency?

Also, do you feel O’Connor’s stories are too violent? When asked about her tendency to kill off her creations, O’Connor said that violence “is strangely capable of returning my characters to reality and preparing them to accept their moment of grace.”

This is so interesting! I really like how you connect the events in O’Connor’s stories to her personal life – I’ve never read fiction in the context of the author’s lived experiences, but now I see how it would provide so much more rich nuance. And this makes me want to try reading Flannery O’Connor!

LikeLike

There’s a whole school of literary theorists who believe you should only evaluate the work of an author by looking at his/her life. On the opposite side are the theorists who believe you should forget the book even has an author, as it is now its own entity. I’m totally with the first group, though I do know that O’Connor got irritated when people tried to analyze her stories at all. She was constantly asked what her work means, and she would say something like, “sometimes a story is just a story.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

I can definitely see the appeal of evaluating the work of an author through the context of their life – it seems to add a lot of nuance.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Another amazing review! You’re doing a wonderful job digging into these short stories. I’m really appreciating this readalong.

It sounds like The Artificial Nigger requires more in-depth study. It sounds like the sort of short story I’d be exploring at school for a few weeks, with multiple re-reads, to pull everything out of it. I like the comparison to The Inferno; it helps me better understand the journey they are taking. The statue must be something important! Otherwise, the story wouldn’t be titled after it, right?

Actually… do you feel like O’Connor does a good job crafting her short story titles? Do these feel intentional to you?

LikeLike

I almost feel like she’s titled her stories the way a lot of filmmakers do these days: by having the title be one line within the movie in which the title is said. That’s how O’Connor’s stories seem to go. Sometimes I wonder if she focuses on the wrong thing to choose as a title. I’m also wondering if I knew more about Dante’s Inferno if there is significance in the statue.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Honestly I can’t blame her for saying (basically) “Wow, you had another one?” I mean, i love my kids, but these people who willingly have big giant broods now that birth control is readily available is A REAL PUZZLER

LikeLiked by 1 person

Back then it was normal to have more children, so O’Connor’s attitude sort of cracks me up. I can’t picture her with children, nor do I ever read anything about her or by her that speaks fondly of children. I don’t think she underestimated kids or thought they were dumb, though, based on her stories.

LikeLiked by 1 person

in fact, I think people who don’t have children are the opposite of underestimating children-they know how smart they are, how much of a headache it’s going to be, so they (smartly) opt-out!!! haha

LikeLike

Opt out, like it’s a spam email, lol.

LikeLiked by 1 person

haha if only it was that easy!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reading your thoughts on these stories has made me think of another difference between gratitude and thankfulness (which is something I mentioned in my reply to your comment on my post). I feel like gratitude is something we expect/demand from other people (“You should be grateful; do you know how many people would love to be in your shoes?”), whereas thankfulness is an attitude or position that we choose for ourselves. Asking people to be grateful for their circumstances, especially without making an effort to truly understand their experiences, basically denies that people are complicated, and that everyone has different reactions to trials and circumstances.

LikeLike

Oooooh, Lou I really like that. I hadn’t thought of gratefulness as something we demand of others, but you’re right. I never hear people say they themselves are grateful, but I do hear people telling others how who they feel is ungrateful.

I’m not big on Marie Kando’s style of getting rid of things, but I do like the way she emphasizes being thankful for our belongings and how they have served us. If I am thankful that my mask helped others around me safe today, that makes me less grouchy about the fact that everything behind that mask feels terribly swampy right now. My glasses steam up, but I am thankful for them because otherwise I cannot see.

LikeLike

When you describe the stories like this, what jumps out at me from the ones I read in A Good Man is Hard to Find is the theme of uncomfortable children. Either, as you say, children acting in a way they shouldn’t or children trying to reach beyond what’s expected of them.

I’m currently reading a book that quotes from O’Connor’s “Mystery and Manners”: “The novelist is required to open his eyes on the world around him and look. If what he sees is not highly edifying, he is still required to look. Then he is required to reproduce, with words, what he sees. Now this is the first point at which the novelist who is a [Christian] may feel some friction between what he is supposed to do as a novelist and what he is to do as a [Christian], for what he sees at all times is fallen man perverted by false philosophies.” I thought it was interesting in light of what we talked about last week and how O’Connor wrote as a Christian. It seems that she saw her role to write about the world (including Christians) as they were, which was often deeply flawed.

LikeLike

There were a few stories in which I felt the children knew more than the adults, but in an unnatural way suited only for fiction.

I’ve heard of Mystery and Manners and thought about checking it out, but I’ve devoted so much to O’Connor this year already! Then again, it can’t hurt 😀

I really like that quote you shared. You’re still required to look. That is the most perfect advice for the pandemic in that I see so much I don’t want to accept, and sometimes I even ignore what I see to satisfy my thoughts, my anxiety, my fears, but it’s still there. Tying religion into what we see when we don’t find it edifying is even deeper and more interesting. Thank you for sharing that, Karissa.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The quote was part of an essay about whether or not Christian artists (singers, writers etc) should be creating art that reflects the world as it is or as we wish it to be. The author argues that it’s part of our job to reflect what we see, to stand in the mess and acknowledge it. I’ve realized in the last few years the privilege that being able to look away entails. Sometimes I have to turn off the news cycle for my own mental health, especially now when it feels so nonstop and overwhelming, but it isn’t right either to completely shut it out or ignore it.

LikeLike

I really love that. Some denominations of Christians are really doers, super active in charity and the community, and I imagine that once they acknowledge the mess, they can begin to heal that mess in a Christian way.

What is the name of the book you’re reading, and who is the author?

LikeLiked by 1 person

The book is called Uncommon Ground. It’s a series of essays from Christians in various careers, edited by Timothy Keller and John Inazu. A lot of Christian art (movies, books, music) seem to think they need to be edifying but they portray a world so far from what we really live in that it just feels forced and artificial. I really appreciate when artists can find that balance.

LikeLike

Another great week of stories! I really like that you provide a bit of background on what was going on in O’Connor’s life while she wrote these stories- for some reason I decided to read the intro of this collection at the end instead of the beginning, so I don’t have much outside O’Connor knowledge to work with and the insight you give always helps click things into place for me.

I also noticed the increase of children vs adults as we’re getting into the second half of the set, that we’re getting more writer characters, and that there’s some exploration of where the farm vs. city line should be drawn, as well as the line of race. A lot of this resonated with me because after my undergrad years I went back home to my family’s farm, and spent a lot of time grappling with newfound differences I was seeing between myself and the “adults,” wondering whether either side was right or wrong or should just agree to disagree, and generally feeling stuck in a place with smaller-minded people. A lot of last week’s characters and dilemmas echoed for me a difficulty with reconciling childhood and adulthood, changing beliefs, and wanting to take a different path than what’s been laid out even while not quite knowing how to go about that. I think the increase in children comes not from O’Connor looking at others’ children from her perspective as an adult, but reconsidering her own childhood and role in her family, from the perspective of an adult child come home (if that makes sense). Knowing that O’Connor was diagnosed and living on her family’s farm while working on these stories really makes sense for me how much more personal I was finding them this week.

LikeLike

I didn’t finish the introduction to this book, either. I’d read most of O’Connor’s book of letters, a chunk of her biography by Brad Gooch, and I do some research in the databases of the Notre Dame library before I write my posts. I haven’t written or researched the post for next Tuesday, but I’m guessing being homebound is a big factor. Next weeks stories are the ones that have the writers in them, and I have a heap to say about it!

I do like what you say about O’Connor feeling like a child herself. I’m thinking she was just homebound when she started writing these stories for Week 3, but Week 4 is going to include stories from when she’d lived with her mother for a while. O’Connor was diagnosed in 1952, Week 3’s stories came out in 1955, and Week 4’s stories were largely from the last years of her life.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m glad I wasn’t alone in skipping/putting off the intro! Kudos for doing so much extra research though, I have a hard time reading about anyone’s life until they’re significant to me- which usually comes after reading their work, rather than before!

And sorry to jump the gun a bit, bringing the writers into it before your reviews had gotten that far! I’m having a much better time with the second half of this collection in general and saw the influx of farm stories as the start of a gradual shift. Very much looking forward to next week’s chat!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh! I didn’t even acknowledge your comment about returning home to the farm. I do imagine you’ll have lots to say next week, then, as you’re just like many of the characters in that sense. I always used to tell my college students that when they went home for the first break, usually Thanksgiving, they were going to find a family that is surprised the student has changed — and why wouldn’t they? There may be some tense moments around the change, and that students should keep in mind that their changing was not something experienced in real time by their family members. I’ve had several students come back and tell me I was right.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Even though I didn’t go home often during my college years, it really wasn’t until after I’d finished school that I really started noticing a big change and lots of differing opinions with my family. They aren’t big on talking, so perhaps it just took that long to have a proper conversation with them, ha. I actually had an interesting talk with my mom at one point about feeling like an adult when you realize you can have different opinions than your parents without being wrong for it- and she said she’d never had a moment like that. She only went to a two-year college close to home and still lives pretty close to her parents; your comment about college students often changing away from home makes me wonder whether she just didn’t get far enough to experience that. In any case, talking about it with her was very helpful in establishing that as a grown person I needed my independence, no matter how close to home I was! It seemed to me O’Connor (or at least a handful of her characters) might have been grappling with a similar need for balance in maintaining a sense of independence while having to depend on family.

LikeLike

I’m definitely going to talk about sons and their relationships with mothers on Tuesdays.

I’m glad you were able to have that conversation with your mom. It’s so strange that it can take a very long time to see our parents as another adult; I would argue there’s a healthy shift in the relationship when it happens. Also, I started to learn more about my mom when we go to that point, and once you get to that point, you may realize that your parents, whether or not they went to college, can be a valuable resource for story writing (ideas, insight, inspiration, etc.).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Looking forward to it! 🙂

I think that’s true! There’s definitely a shift when you can talk to your parents from one adult to another rather than with one party as the authority, and I would agree that it’s a beneficial change by the time it comes. And yes, it’s very interesting to talk to older generatoins (family and beyond) about their life experiences, and when they speak as to another adult there’s a level of honesty and candor there that isn’t always between adult and child. Good writing fodder for sure!

LikeLiked by 1 person