Welcome to the second week of A Month of Flannery O’Connor. To get the full schedule, go here. To read the wonderful discussion from Week 1, head back here.

THIS WEEK’S STORIES:

- The Heart of the Park

- A Stroke of Good Fortune

- Enoch and the Gorilla

- A Good Man is Hard to Find

- A Late Encounter with the Enemy

- The Life You Save May Be Your Own

- The River

SOME CONTEXT:

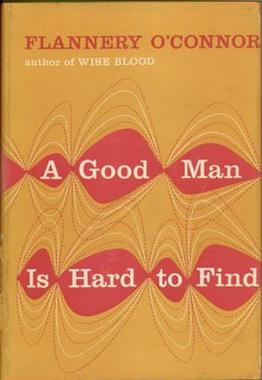

Last week, most of our stories were written to fulfill Flannery O’Connor’s MFA thesis requirements. Some stories were chapters from Wise Blood, which was finally published as a book in 1952. After Wise Blood, O’Connor published a collection of short stories entitled A Good Man is Hard to Find in 1955. The book had “. . . some 4,000 copies sold in three printings by September 1955” (source). As I mentioned, O’Connor was a devout Catholic her entire life. According to Jessica Hooten, the characters in O’Connor’s short story collection, characters like Mr. Shiftlet in “The Life You Save May Be Your Own,” are often autonomous to the degree of selfishness. They may not be solitary physically, but are alone in their minds, such as the grandmother in “A Good Man is Hard to Find,” who manipulates, complains, and is prideful (source).

There are selfish, prideful characters in many of O’Connor’s stories this week, suggesting the author believed that a person who did not join a community, perhaps even implying a religious community, perhaps a person who had not found God, was evil. Let’s explore one story at a time!

EXAMINING THE second SEVEN STORIES:

“The Heart of the Park” (published 1949 in Partisan Review, part of Wise Blood pub. 1952) is a story I find interesting because separating this chapter out from the rest of Wise Blood gives readers a chance to get to know Enoch better. He’s a horrible person, but because I don’t know what he’s going to do next, I can’t look away. Enoch has ritualized his days: first he spies on women at the pool, then gets the malted milkshake and harasses the employee, then checks on all the animals and gives them dirty looks and curses, and finally he visits the mummy. Catholics, if nothing, are ritual-loving people. Enoch’s sins seem obvious, but he’s also one of those autonomous people I mentioned above. He drags Hazel around the zoo and has no qualms with spying and harassment. Would he be evil in O’Connor’s opinion?

“A Stroke of Good Fortune” (published 1949 in Tomorrow then reprinted in A Good Man is Hard to Find collection in 1955) is one of those stories I enjoy for the rare perspective of a woman who did not want children before birth control was widely available . “To Room Nineteen” by Doris Lessing is another brilliant piece I recommend. What begins with determined woman named Ruby becomes worrisome. I was convinced her lack of oxygen was leading up to a heart attack (or a stroke, given the title?). Ruby, too, is autonomous. No doctors, denying help from neighbors, and her brother might as well be dead for as useful as she finds him. Avoiding doctors is a source of pride. What might her pregnancy symbolize? This baby seems to come from “nowhere” based on Ruby’s reaction, and I saw her as a Mary figure about to give birth to a baby that will bring her close to God and her husband.

“Enoch and the Gorilla” (published 1952 in New World Writing, then part of Wise Blood — 1952) is a wild chapter. What is the significance of Enoch beating up a man in a gorilla suit, burying his clothes (which implies he murdered the man), and then running around in the gorilla suit himself? When I listened to the audiobook of Wise Blood I struggled here because I didn’t realize what was going on. O’Connor writes on a slant, especially the way she describes Enoch putting on the suit as being like two humans joining. In a weird way, Enoch the autonomous becomes a young man reaching out. He shakes hands while wearing the suit, his first handshake since he moved to the city. But we know from “The Heart of the Park” that Enoch hates animals. Is it that the city loves the zoo animals, so Enoch must renounce himself as a man, become a gorilla, and find community? The mind boggles in delightful ways.

“A Good Man is Hard to Find” (published 1953 in Modern Writing I and 1955 in self-titled collection) stood out differently to me; The Misfit’s father died of the Spanish flu of 1918 in 1919, reminding me that pandemics go on until we’re vaccinated. Though a serial killer, The Misfit and the grandmother are both autonomous figures bullying others. Instead of defining “good” as Christian/Catholic, the grandmother tells The Misfit he has good blood, a good family — that he isn’t common. People frequently view The Misfit as a Christ figure because both paid for the sins of others. But if O’Connor felt autonomy to the point of selfishness was a sin, I’m not so sure. And I’m always confused when The Misfit says he wished he was there when Jesus raised the dead. I’m not religious, but I thought Jesus is supposed to raise the dead on Judgment Day, a day yet to occur.

“A Late Encounter with the Enemy” (published in 1953 in Harper’s Bazaar and 1955 in A Good Man collection) has another autonomous character, even though he requires a lot of assistance: a 104-year-old soldier whose rank is bloated, but he loves photo ops and kissing young women he doesn’t know. He ignores his daughter unless her event centers on him. By rejecting his military past, the man keeps himself alive. I thought it clever how the procession of graduates in their caps and gowns triggered a memory of charging soldiers, which is what ends the selfish old man.

“The Life You Save May Be Your Own” (published in 1953 in Kenyon Review and 1955 in A Good Man collection) was a bit tricksy at first because I couldn’t figure out what everyone was up to. A mother who wouldn’t give up her child but does. A solitary man who doesn’t know what a man is. A handicap that on the surface plays little role in the plot. I felt the story suggested that Mr. Shiftlet, whose name is so close to “shiftless” and implies impermanence and autonomy, suggested that he married the daughter for access to the car, which would return him to his mother. I saw connections to Zora Neale Hurston’s stories with the trickster figure, and both writers were southern women. Beyond the symbolism, I wondered how the daughter, who couldn’t speak or care for herself, would figure out how to get home after Mr. Shiftlet abandons her.

“The River” (published in 1953 in Sewanee Review and 1955 in A Good Man collection) contains two selfish, autonomous people: the boy’s parents. Neglected, he must rip the pages from his books to get new ones, and he absorbs a different identity to find community with his babysitter, knowing she’ll be pleased if he has the same name as her beloved preacher. It’s interesting that Catholics have priests but O’Connor’s religious figures are often preachers. I felt Henry made decisions too chock-full of symbolism to be a believable four-year-old boy, but I appreciated the way he’s described as a survivor, going so far as to drown himself to get ride a river to religion, community, and being counted. So, what’s the significance of the man trying to rescue Henry from drowning/finding religion being named Mr. Paradise?

NEXT WEEK:

- A Circle in the Fire

- The Displaced Person

- A Temple of the Holy Ghost

- The Artificial Nigger

- Good Country People

- You Can’t Be Any Poorer Than Dead

- Greenleaf

QUESTIONS:

- Did you see connections between any of the stories and characters?

- Did you like the stories better from Week 1 or Week 2?

- Does weaving in religion, possibly where it’s not needed, weaken O’Connor’s stories? I’m thinking especially of that line, “Why you’re one of my babies. You’re one of my own children” right before The Misfit kills the grandmother.

Great post, as usual! 🙂 I did like this week’s reading better, perhaps because I’d read two of the stories before for school and felt I had a decent grasp of them already (A Good Man is Hard to Find, and A Late Encounter With the Enemy). I also really liked A Stroke of Good Fortune- I saw the pregnancy more as something that would doom the narrator than save her; I’m not sure how that impression fits with O’Connor’s stance on religion though, so perhaps I was just reading into it what I wanted to.

I actually liked all of the Enoch stories this week, even though I don’t like him as a character. I was a bit confused by The Heart of the Park however- Enoch seemed to think he knew something or had some advantage on understanding the mummy, and yet all he does is show Haze the display, so I felt like I was missing what it’s significance was for Enoch. But I actually had a slightly different opinion on Enoch and the Gorilla than you did- I thought it was a demonstration of how society had corrupted Enoch (by ignoring him, perhaps, by refusing to include him), turning him wild as a result. I think that fits in with your theory on autonomy being condemned by O’Connor though, so perhaps we came to the same point from different angles! I’m not generally big on stories about religion so I did like that a lot of these focused on it kind of obliquely, like you mention with pride, sense of community, etc. The focus is more on traits and internal morals than a lot of church-going; I appreciate that.

I also wondered about Mr. Paradise’s name- I thought perhaps he saves people from that river frequently; if he lives near there and knows it has a strong current perhaps he’s usually a savior, though I’m not sure how it fits with the fact that he doesn’t actually manage to save the boy. As for “You’re one of my own children,” in A Good Man is Hard to Find, I think the grandmother simply came to realize too late that her religion was supposed to connect her to other people rather than hold her superior! She judged the Misfit before she had all the information, and had to learn in the end that she wasn’t above him, or anyone else.

LikeLike

The WEIRDEST part about all of O’Connor’s writing, to me, is that none of it seems very Catholic! She doesn’t even write about priests, but preachers. I know she and her family were in the minority by being Catholics, so maybe she’s writing what she saw instead of what she believed.

I do like your interpretation of Enoch. He’s kept off to the side and ostracized (maybe because he’s a creeper with women), but it’s turned him into something not so human. About the mummy…I almost wondered if the mummy was supposed to be like the unrisen body of Jesus post-crucifixion. It’s unclear, but something about his “wise blood” tells him that Haze needs that mummy.

That’s an interesting idea about Mr. Paradise. I also wondered the significance of the giant peppermint stick. I mean, perhaps it’s candy to lure the boy (smart move!), but what is the significance of it being the size of a police baton? It stuck out to me as unusual.

Oooooh, I like that interpretation of the grandmother’s utterance. Good one, Emily!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m not super well-versed in religion, but I always thought “preacher” was the country way of saying “the guy who gives the sermons” rather than a term specific to any particular religious branch. Preacher is still a pretty common term in my area, especially among older folks. I thought maybe it was the same in Georgia. I think it’s still worth noting that she’s not using “priest” though, there is a sort of informality to “preacher” that fits with your point!

That’s an interesting idea! I kept remembering how Haze remembers seeing the woman in the coffin-like box at the circus in The Peeler; the description of the mummy echoed for me how that earlier scene had been described, so I had some trouble seeing past that and making fresh connections. Giving it a religious symbolism would make sense- am I remembering right that the school Enoch went to as a teen was a religious school? If so I do think he could make a connection to a crucified Christ.

I forgot about the giant peppermint stick! It did seem like there was a lot of symbolism happening at the end of that story that I wasn’t quite grasping- tbh I was a bit caught up in the fact that the boy was actually drowning! Somehow I didn’t expect the story to go that far, especially as this does, like you mentioned in your post, link his baptism and entrance into religion to his ultimate doom! The unusual name and giant candy almost seem like the stuff of hallucinations or imagination just from their sheer bizarreness, but I can’t figure out what they’re supposed to mean to the boy whether real or invented.

Thank you! 🙂

LikeLike

A priest is mostly associated with Catholicism, as are reverend, father, and pastor. Though, some Lutherans call their leaders priests. Preacher is used in many cultures. I get the vibe O’Connor would be specific about this, but I’m not sure.

Enoch says that he went to that boys’ Christian academy over and over, like it traumatized him so bad he has to repeat it. I think he’s a young man who allows religion to wash over him, but it’s in his guts as something he can’t deny. Everyone in Wise Blood seems surreal to me. O’Connor seems to tamp that down a LITTLE in the next stories, but we’ll talk about that next week!

LikeLiked by 1 person

That mostly matches up with my knowledge as well, although I grew up Lutheran and our church leaders were always called pastors. I suppose in my mind the difference between preacher and priest etc. is that preacher is more of an informal descriptor of the job they’re doing, whereas something like preist or pastor or father is a more official title. Maybe in O’Connor’s stories the individual characters who preach are not as important as the general role they’re filling?

Yes! I couldn’t remember the name of the school but I recalled him repeating it. (I was actually reading two books with boys’ schools at the same time and wanted to make sure I was remembering the right one!) I think that’s a good description, letting religion wash over him even while it’s already a deep undeniable part of his life, thanks to his education.

LikeLike

O’Connor’s education was “in the city’s parochial schools. After the family’s move to Milledgeville in 1938, she continued her schooling at the Peabody Laboratory School associated with Georgia State College for Women (GSCW), now Georgia College and State University.” I love that she spent time both in Catholic and public schools so she could see the differences. I wonder if some of her feelings about both types of schools come through Enoch and his feelings about religion.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah, that’s interesting! I didn’t realize her education was varied that way, but it would make sense for that experience to shape her perspective and come through in her characterization. I could definitely see Enoch as a reflection of that!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ok, I got here in the end. I’ve just read A Good Man etc, isn’t it an astonishing story. I have sisters in law like the grandmother who you’d love to shoot every now and then just to stop them talking. Reading your commentary I’m sorry I’m just cherry picking, it seems clear that O’Connor intended her stories to be read as collections and one day I must do that and see how the stories and the characters hang together.

LikeLike

Yes, the chapters that turned into Wise Blood the novel were, according to O’Connor always meant to be a novel. I do find some of them have a rough go of standing on their own.

The weird part about the grandmother in A Good Man is that even though she drives you insane, I also laughed when the cat escaped after she accidentally kicked it when she realized she’d sent her son on a wild goose chase.

LikeLike

This week’s selections were a rough ride!

In general, I find myself disliking the bits that eventually became Wise Blood. I can generally handle unlikable characters as long as I am getting something from the story that bears out the effort. When Enoch beats up the jerk in the gorilla suit and steals it, though, it did get me thinking. This goofball is stealing a gorilla suit because he wants to be the one who gets his hand shaken, since his time in the city has been so dehumanizing. He may as well go feral in a gorilla suit. I took his burying his clothes to mean he was leaving his humanity behind to become one with the gorilla.

A Stroke of Good Fortune and A Good Man is Hard to Find each feature characters you are supposed to dislike, and the reader is invited to experience a downfall for each. In the first case, this poor cranky lady is just trying to get her groceries home to make some food she doesn’t like for a brother she doesn’t like and boom, it seems pretty clear she is having a baby she never knew was coming. Leaving sole responsibility for contraception on one party in a relationship is not a recipe for luck. In the second case, we have an annoying grandmother flanked by these two snarky grandkids who I would gladly have read an entire collection about. Then terrible things happen to them all. I am sure there is plenty of room to explore the exchange between the old woman and the Misfit, but it was just too awful.

In each of these stories, I found myself without anyone to root for aside from the snarky grandchildren. And they snuffed it.

The high point of the reading for me this week was A Late Encounter with the Enemy. Something about the way the story was framed had me engaged and ready to see what was going to happen. I’ve had boisterous and somewhat ancient grandparents that reminded me just a bit of the old general, and knowing the narrator wanted nothing more than to have this guy on stage when she received her degree feels way too familiar. Where one may expect her father to see her great achievement and simply not care, the general finds a way to provide his daughter the ultimate criticism. That was a hoot.

I read The River and was immediately just sad sad sad. This poor kid’s parents just want to party all the time and don’t pay any attention to him. He gets baptized and is told that he finally counts. That’s all he wants, right, to count? Once he is taken home and we see just how neglected he is, we watch him form a plan to get right back to where he counts.

When I think about these stories, they certainly aren’t comfortable, or merely entertaining. This isn’t the book version of a popcorn movie. However, each of them makes me feel something. I dislike the narrator, or the plot makes me sad, or a particular moment in the story just makes me think about how good or awful people are. The stories may not feel good, but they’re effective at what they are trying to do. I hope next week Flannery is going to try to cheer us all up!

LikeLike

I both smiled and felt guilty/sad when you closed the book after finishing “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” and said, “Well, that was fuckin’ awful.” Those grandchildren are so terrible! They remind me a good deal of Shirley Jackson’s children and how they are presented in her memoirs, Life Among the Savages and Raising Demons. To be honest, children who both seem bad and confident scare the crap out me. Perhaps you’ll be relieved to know more children are featured in the upcoming stories? I did want to root for the cat in “A Good Man,” as it was such a realistic but exaggerated and fearful animal once the granny bumps the basket just a smidge.

I really like your interpretation of Enoch going feral. I had a similar reaction, thinking that Enoch sought out companionship and connected it to the way he hates animals, but the city loves that zoo and the animals. It does remind me of the way people will treat animals better than other humans. I keep thinking about how one-eyed animals are “SO HOT RIGHT NOW!” on Reddit. But are we as kind and warm to a disfigured or disable human? I don’t think so.

Haha, now I’m wondering which of your grandparents was like the general. I saw your granny give your mom a hard time once or twice, but truthfully, I see your mom in the general character more than your grandmother. I definitely did not think of the general dying as a criticism, but now that you’ve pointed it out, much like the Fex Ex logo, I can’t unsee it.

For some reason, I lost track of the little boy’s feelings about counting. It’s said once or twice, but I kept my eyes mostly on that babysitter. I kept thinking she would do something religious and drastic (I guess having a kid dunked in a river face first while dangling him from his ankles is a bit drastic) that my gaze moved away from the boy, thinking that at four-years-old he wouldn’t be able to make decisions. Your interpretation of him is much smarter and more beautiful than mine.

I’ve read many of the stories for next week, and they don’t seem as dreadfully sad as these (so far). I’m glad you’re experiencing a range of feelings about the story and continuing to think about and process them, but I’m afraid if you Google “Flannery O’Connor” and “cheer,” you may very well break the internet.

LikeLike

As I was reading these stories, I found that I kept having to remind myself that O’Connor was Catholic. There’s a lot of Christian influence and religion here but very little that I recognize of Catholicism. (It’s possible I’m more familiar with the Protestant references than the Catholic ones.) There seemed to be a lot more references to preachers and the sort of Southern values of “good people” that I associate with Baptist-style Christians. I noticed too that “blood” and who your “people” are is a recurring theme in her work.

LikeLike

Yes! I made a similar comment to Emily about “preacher” vs. “priest.” Though it’s been a long time ago, I was raised Catholic and then lapsed. Later, when I went to University of Notre Dame, Catholicism is everywhere, but it still didn’t look or feel like what O’Connor writes. Karissa, wasn’t O’Connor Catholic in a place and time when they were uncommon? I think I remember talking with you about that.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, I think we did. I believe just being in the southern states and being Catholic at the time, O’Connor would have definitely been in the minority. The way she talks about religion with itinerant preachers and baptisms in rivers and Bible salesmen is much more what I would associate with Southern Baptist or Pentecostal. Which makes sense given the setting but I don’t see much Catholicism in her writing. (Except maybe in “The Displaced Person”.) As far as I know, Catholics wouldn’t say “preacher” and only a few Protestant denominations use the term “priest”.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah yes, the ol’ Catholic Guilt. It’s not just a saying, is it? My mother-in-law is Catholic, and thank god she doesn’t guilt us (she doesn’t go to church as often as she used to anyway) but HER mother, i.e. my grandmother, god rest her soul, was very catholic. When she found out my husband and I got married on a beach she tried to convince us to do it over again in a church (insert eye roll here)

LikeLike

When my husband and I got married in a really old movie theatre that could also do plays on a stage, people were curious about how that would all go together. Which religious leader would marry us? None. We had a judge who came (lovely man). Don’t judges just do courthouse weddings? No, they come and party with you afterward if they’re available.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A theatre? What a gorgeous idea, I love the sounds of that. And who knew Judges were such partiers? LOL

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great post! I love how much thought you’ve put into this and connected all the stories you’re reviewing while still giving them their own space. You’re a wonderful reviewer of short stories. Keep up the awesome work!

Did you feel less lost in this second read of Enoch and the Gorilla? Did reading the words feel different from listening to the audiobook?

I’m intrigued by your question about whether religion weakens O’Connor’s stories. You only mention religion in 4 of the 7, and one of the mentions is so tangential I almost missed it. I wish I could contribute to answering this question. But as I haven’t read the stories, I’ll ask to hear more details on your opinion instead. Do you think religion is weakening her stories? If so, how?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! I do some research about the time around which O’Connor published the stories for the week and find a critical lens through which to analyze the stories. It feels like my grad class on literary theory, which I took, oh, about sixteen years ago (WHHHAAAAT).

I didn’t feel lost reading about Enoch this time because I re-read a couple of spots 2-3 times and really pictured what he was doing, whereas with the audiobook it’s there and gone with the speed of the audio narrator.

I asked about religion weakening O’Connor’s stories because there are times when she has this interesting story that’s going in a certain direction, but then she’ll add a reference to mercy or salvation in a way that seems random. I wonder if she felt the need to add religion because it was fundamental to her existence, but if it didn’t always fit. Otherwise, there are some cues I’m missing that should have led me to the religious lesson!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Haha — time flies, doesn’t it?

I often wonder if I’m missing something when it comes to religious references in texts. I feel like I catch them all, but rarely do they all feel like they are leading to some big realization in the story. I feel a bit better knowing that you, a learned woman with great experience in literary theory and criticism, runs into this sometimes, too. I’ve always attributed it to the fact that I don’t know enough nuance when it comes to Christian beliefs… but perhaps you’re right, and the author just wants their beliefs to be a part of the text because they think it’s necessary as a part of themselves. I’ll ponder this some more. Love it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sorry I’m getting to this so late—it’s been such a weirdly full week for me. I liked this set of stories more than last week’s. My favourite from this bunch was “A Stroke of Good Fortune,” for the reasons you mentioned. I was also unexpectedly moved by “Enoch and the Gorilla”, which stayed with me when the details of the rest of the stories have become fuzzy. That last scene of him in a gorilla suit, just wanting a handshake, was particularly memorable. I dislike Enoch, and I was just mostly confused by “The Heart of the Park”, but in the gorilla story I felt some compassion for him and his desperation for human contact. He had to dress up as an animal to be noticed. I’m also not sure that he hates animals—I actually thought he was more jealous of them.

It’s an interesting point you raise about religion. The vibe I’m getting from her stories is one of disillusionment towards religion, or belief turning into disbelief, like in “The River” Mr. Paradise didn’t even get to save the boy from drowning, and in “A Good Man” The Misfit tells the grandmother that he doesn’t pray because he doesn’t need the help. But it also seems like O’Connor enjoys playing with religious symbolism more than making a point (like baptism in water symbolizing rebirth, but also the place where the boy died). Also, on a side note, Jesus raising the dead may refer to the incident of raising Lazarus from the dead, and the synagogue leader’s daughter, among others. These events supposedly were powerful catalysts for belief.

LikeLike

Well, now you’ve gone and made me teary-eyed over Enoch! Although I felt the same way about him that you did, something about the way you phrased it made me feel sadder.

It does seem like O’Connor is poking at religion, and one vibe I got from her letters that I read was that religion should be questioned and tested. Blind faith without a strong foundation didn’t seem to be what she was about.

I didn’t even think of Lazarus, and I don’t know the story of the daughter, but now I’m wondering if The Misfit felt that if he had witnessed one of these powerful events, he could have been a better man, one who believed in God, mercy, redemption, etc.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hmmm, that clarifies things. I wonder if she’s still a believer when she grapples with religion like that.

Re The Misfit, I actually think he wouldn’t have become a better man. It’s like how people used to say, “I’ll believe when I see X,” but when X happens they’ll find more reasons to disbelieve it, if they already were disinclined to believe in the first place. The Misfit seemed really disillusioned by then. I found it interesting though that he had quite a long conversation with the grandmother when the others had killed off her family so quickly. Was there any significance to that?

LikeLike

Oooooh, another great point about The Misfit being disillusioned. It seems like many of O’Connor’s characters are the type of people who want the world to fit with how they see it, and when the world won’t conform, something bad happens to them.

Truly, I’m not sure what to think about the length of the conversation between The Misfit and the grandmother, nor do I know the significance of the boy and father being murdered first, then the mother, daughter and baby. Perhaps it’s not decent to commit murder in front of women, even if you’re going to murder them too?

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s true—they try to make the world see their point of view, but in the process they become just more alienated from it. I think this is what makes her works so bleak.

Ha, I like how he maintains a hint of Southern manners even before murdering people!

LikeLike

Southern people be like that. 😬

LikeLiked by 1 person