The Girl Who Reads on the Métro by Christine Féret-Fleury, translated from French by Ros Schwartz, is a hard book to define or explain. A novella, yes. A contemporary novella, definitely. Not quite magical realism, but it feigns a left punch that way. Possibly existentialist fiction? According to the website Early Bird Books, an existentialist novel is:

. . .typically characterized by an individual who exists in a chaotic and seemingly meaningless environment, [and] forces the protagonist to confront his/herself and determine his/her purpose in the world.

Féret-Fleury’s isn’t a terrible complicated plot; it is that it doesn’t all go together or arc, like I expect a book to do. And I’ve found this characterization with other translated novellas, such as Mile End by Lise Tremblay, The Room by Jonas Karlsson, The Camera by Jean Philippe-Toussaint and Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata.

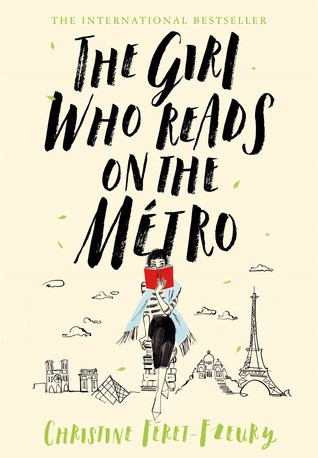

In The Girl Who Reads on the Métro we find Juliette, who is not reading on the métro but people-watching, especially those with books. She’s also not a girl. She’s an independent woman living in Paris. Anyway. She gets off the métro for her job as a real-estate salesperson, one she’s not great at because people don’t seem interested in listening to her. They’re too distracted by phones. Perhaps busyness is a point the author tries to make?

As she’s walking home, Juliette sees a used book shop with a book crammed in the door to prop it open. A girl (yes, an actual girl) encourages her inside, where we find her father, Soliman. He owns the place. Thinking Juliette wants to apply to be a passeur, Soliman gives her books to hand out to exactly the right people. She must follow people around, learning their patterns and personalities from a distance, before she gives them each the perfect book.

Weirdly, Juliette occasionally reading on the métro isn’t a plot point, though readers know she is the eponymous “girl” because of the blue scarf she wears that matches the one on the cover. And she never follows anyone to give away a book. Instead, Soliman asks her to move into his house/book shop to watch his daughter for weeks, maybe months, while he goes to do a thing. What thing? We don’t know.

Juliette is one of those bookish dreamers who feel stories help her live a full life, even though she doesn’t physically move around a lot. Soliman is worse; before he left for whatever reason, he hadn’t departed his home/book shop in ages. We don’t learn why, except the vague implication that books make your brain travel, even when your body does not.

Overall, I didn’t dislike The Girl Who Reads on the Métro, but because I had no excitement about what would happen in the plot (again, no arc), I wasn’t eager to pick it up. Juliette rolls with whatever strange thing comes her way, but she doesn’t experience a noticeable growth, either. Getting back to the definition of existentialist fiction, Juliette’s world isn’t chaos but it is meaningless. She doesn’t really learn about her purpose in the world, but I can see how the author asks the reader questions about who we are and what we’re doing with our lives.

Perhaps you may enjoy The Girl Who Reads on the Métro simply due to the sentences, which are lovely. As Juliette repairs a van, she wonders what if . . .

. . . the story of the world as she knew it was one big rumor that some people had taken the trouble to set down in writing, and which would continue to evolve, again and again, to the end.

It’s quite a thinker, one of those existentialist quandaries that will happen when you do things like think about the human structures imposed on the world, or how outer space is so big we can’t even fathom it. You’re imagination will run wild and practically scare you.

An interesting novella that I found easy to put down and wished would push harder on interesting potential plot threads that were left alone.

Hmmm yah I don’t think I’d like this one. Too much existentialism. I took a philosophy course in Uni and HATED it because there was nothing concrete in it. I’m just not that kind of thinker-I need structure!!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Every so often I bring up this argument about why philosophy completely blows my mind, and not in a good way: every philisophical argument I’ve ever read is a dude who creates scenarios and the says that “of course” no one/everyone would reasonably agree with ____. And it was never a thing I agreed with, and I was also made to feel unreasonable! As someone who used to teach using all three rhetorical strategies (ethos, pathos, logos), it makes no sense to me for someone to use all personal logos and then think I’m — what, stubborn? unreasonable? — if I don’t agree.

LikeLiked by 1 person

If you’re interested in more French fiction in translation, you might try A Novel Bookstore by Laurence Cosse or The Red Notebook by Antoine Laurain. Less existential, more character-driven, I think.

LikeLike

Thanks so much, Kim. Do you read a lot of works in translation? I tend to stumble upon them — a book sounds interesting and I get it, then realize it’s a translated work.

LikeLike

I challenged myself to read a lot more translated fiction in 2018. It didn’t go as well as I hoped, but I did read a lot more books from around the world, so I called it a win.

LikeLike

Nice! I tried reading more books by authors from Africa for a while. I even printed a map and colored and labeled the countries. I think I only go through five. Yeesh.

LikeLike

African fiction can be hard to find. I had some difficulty locating African novels, too. Ann Morgan addressed this in her book, The World Between Two covers, which I recommend if you are looking to increase the amount of translated fiction you read. She ran into the problem of availability, and the fact that in many African nations, there just isn’t much– if any– publication work being done.

LikeLike

Anecdotally, I think more African works are being translated into English. At least, I keep seeing more bloggers reviewing works by African writers, and this is promising! I try not to buy books unless I’m given a gift card, so I have what the library makes available. I’ve found quite a few audio books from countries like Sri Lanka, North Korea, Thailand, Cambodia, etc.

LikeLike

Well that’s interesting that the title doesn’t really live up to the title – but instead of reading books the main character is reading people….it would have been an interesting story of she did serve as a match maker between people and books. Your review does clear up the misconception I had based on the title. But your mention of Convenience Store Woman makes me consider picking this up because that one made me think, not in a philosophical way but about people and society and assumptions. So I’ll keep this one on my library list for the future

LikeLike

And even if you don’t love it, the short novella length makes it a fairly quick read. I’d love to read wheat you thought of it, as I know you and I tend to notice different things when we read the same book.

LikeLike

It struck me that you had the same sort of feelings about other translated works from different countries that you’ve tried. Do you think there’s something unique about American novellas or novels that has conditioned your brain to expect a certain kind of plot development?

LikeLike

For some reason, the translated FICTION I’ve read is all in novella form. Novellas are really, really hard to stick the landing, regardless of the language, and I’ve found that a number of them lean toward something like grounded whimsy. Nothing every becomes an “adventure” of the wacky nature we expect in the U.S., but there is something a wee bit magical going on. With such a short form, though, the story can abruptly end or give the reader no sense of where the plot is headed, which makes it hard to want to read the rest of the story.

Translated nonfiction, to me, reads very much like nonfiction in memoirs, so now I’m wondering if it’s not a translation issue, but a novella issue.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I saw this in a bookshop today and got mum to buy it as a christmas present, not for me, but I was intrigued enough by your review and by a glance through the pages to hope to read it some time during the coming year.

LikeLike

You might read it differently than I, especially since we seem to read different genres (except our shared love of science fiction). It’s a little thinker, but didn’t have much in the way of plot. Please do share a review when you read it! For whom did your mom buy it?

LikeLike

For my next brother down who is a Francophile (well that was my excuse when I recommended it).

LikeLike

Ah! If he’s into graphic novels AT ALL he must read The Rabbi’s Cat by Joann Sfar. He’s a French writer whose work is just delightful. The book comes in English or French.

LikeLike