In my last year of undergrad, I realized I had to take a history course to graduate. Thumbing through the course options guide, I noticed a graduate-level class: Black Detroit. Long a fan of the Detroit Tigers and interested in the city’s unique spirit, I signed up. I was immediately warned by the professor that reading history books was not like reading novels for my English major. Convincing him I was okay, he signed the waiver allowing me, an undergrad, into this graduate course. I was terrified of failing.

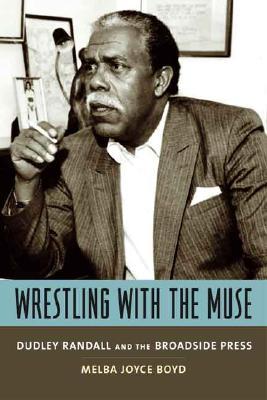

Black Detroit ended up being my favorite class of my entire education. Covering everything from Motown Records to the great migration, unions to organizations that met black folks when they arrived to “clean them up” and “properly” represent the race to white Detroit, there was so much to uncover. I wrote a paper about Amiri Baraka, a black poet. You may remember that one of the only all-black poetry presses was started in Detroit by Dudley Randall.

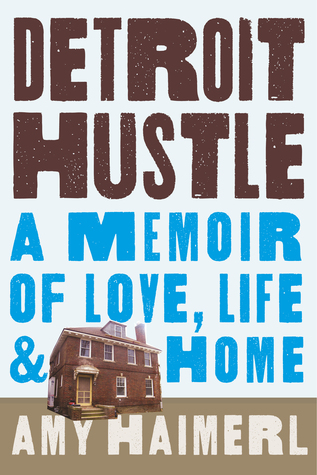

Thus, Detroit Hustle caught my attention when I was in an indie bookstore. Where is Detroit today on housing? I’d read about Detroit’s super cheap homes in the news, how artists are moving in for next to nothing. I was hesitant that the entire memoir would be about gentrification, but I purchased it. Gotta support indies, right?

Amy Haimerl grew up in a poverty-stricken area in Colorado. Her father started his own business, which he lost during the recession circa 2008. She went to college, became a journalist, and moved to Red Hook, a neighborhood in Brooklyn. Even at this point, I was skeptical. She writes, “Our rent was topping $3,500 a month, and we were working just to keep our middle-class life afloat.” I’m not well-versed in the financial class system, but $3,500 doesn’t sound like the middle to me. She and her husband were active in the community — volunteering at farms, organizing free movies in the park, etc. Eventually, tourists come to the area and rent goes up. Haimerl implies the area is being gentrified, and she’s disgusted.

Luckily, just before Hurricane Sandy destroys Red Hook, Haimerl and her husband had moved to Ann Arbor, Michigan so she can take a visiting professor position. They want a forever home, though, that is in a neighborhood similar to the now-decimated, waterlogged Red Hook. She notes, “. . . we wanted a place that was forging its future, not relaxing on its accomplishments. We wanted a working-class town with an entrepreneurial spirit.” Detroit it was.

The book is well-written and easy to follow along. Really, the question is should you read this book for the content?

There are lots of parts that feel icky. The house they purchase is $35,000, which they pay for in cash. Haimerl hopes they can get a loan for the massive renovation by putting down $100,000 in cash, but they don’t. Banks aren’t willing to invest in Detroit homes that, once renovated, are still worth less than the loan because of Detroit stigma.

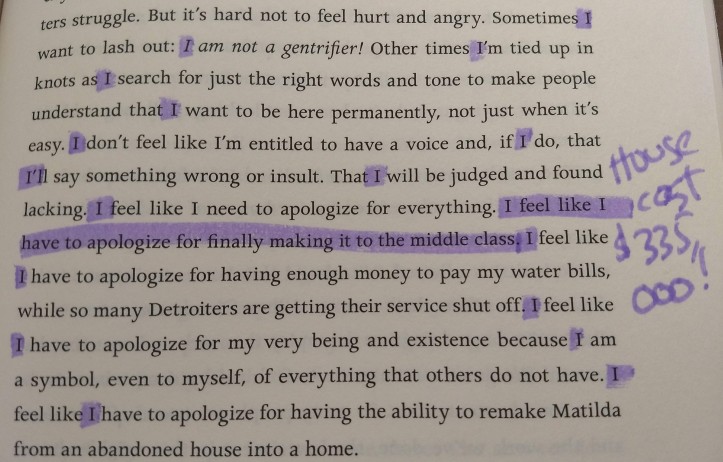

As time goes on, Haimerl whines that she feels like she’s obligated to apologize for being middle class. She admits her house, post-renovation, cost over $400,000. Not very middle class to me. To get an idea of the size of this house for two people with no children (and none wanted), it has 65 windows, 24 interior doors, and 4 bathrooms. When she and her husband run out of money to pay contractors, it’s donated by family.

Her privilege is everywhere. Think of the black families that were displaced after neighborhoods collapsed due to white flight, who can’t get loans because of their skin color, who were evicted during the recession. Think about this: “[Detroit] is still 83 percent African American, but you can walk through downtown and see very few black faces. . . .On the outside I look like a gentrifier. I appear white and affluent. But in my head I am still just a poor girl from [Colorado].” Erm, I’m not sure what Haimerl means when she says she “appears white.” She is white. I’m not sure why she identifies as “a poor girl” when she’s in her 40s and has been affluent for quite some time. Think about that $135,000 in cash she had for her house.

Race is oddly everywhere and no where in Detroit Hustle. The synopsis claims the memoir is more about the people of Detroit than the renovation, but I could get over how often Haimerl used the word “I.”

Yes, she acknowledges that she has privilege, but she never owns it. There’s always a “but” close behind. She mentions that their dog, a rottweiler, isn’t what people think of as a white gentrifier’s dog. It’s a breed historically connected to race, in case you aren’t picking up what I’m throwing down. This detail coming from Haimerl, who “appears white.” Right.

Near the end of the memoir, page 262 out of 269, Haimerl drops a bomb on the reader, and I wanted to call bullshit on everything she said about community building and saying “hi” to neighbors:

But standing in this party, filled with beautiful people I love, all of whom have the best of hearts and intentions for their lives and this city, I can’t help but notice that we are a gaggle of all-white faces.

These neighbors she’s been writing about the whole book? They’re all white in a city with a population 83% African American. That doesn’t include the 5% of people who identify as Hispanic or Latino. Which means the percentage of white people is tiny. And she just happened to find a white community? Why keep this from the reader until the end? I think Haimerl isn’t being terribly honest with herself — or her readers. Perhaps the book should have been called Dear White Guilt: Neener, Neener, Neener, I Can’t Hear You.

That course you took sounds fascinating! Just from the things you mention, I can tell that it had a lot of information and perspective that many courses don’t have. As for the book, it’s interesting how the elephant in the room, so to speak, isn’t admitted, discussed, and so on. And yet, it is, as you point out, obviously there.

LikeLike

Indeed. And what kind of journalist conceals the facts?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was born in Windsor but I’ve only been to/through Detroit a few times (although my family moved through a series of other small Cdn cities and towns when I was very young, so crossing the river wasn’t second-nature once we’d moved east of all that): still, that course you took sounds terrific. Do you know Wayne Grady’s Emancipation Day, a novel? It’s set in Windsor but also has significant scenes set in Detroit and I think you would appreciate his perspective (although it’s a quiet and slow-burning read). Although I think my response to this memoir would be the same as yours, I wonder if there’s something to be said for the fact that some readers might, at least, be forced to consider that Detroit is not necessarily what they’d expected, even if this woman’s experience only represents a small portion of the already small 17% of the population.

LikeLike

I haven’t read Emancipation Day, but I do love novels set in Detroit. So many novels about but cities are set in Chicago or New York, and I don’t get why. Detroit was often the hub that created movements that spread to other cities.

LikeLike

First question: Why does Notre Dame have a graduate course called Black Detroit? Just due to proximity? Or is there something special about Detroit compared to other cities in regards to race?

Second question: What were you expecting going into this novel? I can make assumptions based on reading between the lines above, but I’d like to hear your thoughts before I put words in your mouth.

Time to play Devil’s Advocate. Haimerl came from Brooklyn, where the median home cost is $781,200, and moved to Detroit, where the median home cost is $44,800. If she is surrounding herself with the same sort of people who were in her social circle in Brooklyn, why would her perceptions of being middle-class change? What is there in her life which says “Your circumstances are suddenly very different.”? It’s easy to imagine they went from earning the median annual income of white Brooklyn residents ($69,000) and were able to move to Detroit and pay for a house with cash.

That said, I don’t know if I’d finish this book. Based on your review and the highlighted photo, just like a whining woman. There seems to be no nuance. Plus, I don’t want to read someone HGTV story. This isn’t about you renovating your house. This should be about what gentrification truly means, what your experiences are in both Brooklyn and Detroit, and how you are able to compare and contrast these experiences to bring light to what gentrification looks like in America today. Sad Jackie wanted more from this book than Melanie received.

LikeLike

First Answer: it wasn’t Notre Dame that had the class, it was Central Michigan University. The professor went to Wayne State University, which is a huge college in Detroit with lots of excellent history. So, when he was hired at CMU, he taught in his specialty. Notre Dame actually has very few classes that focus on the black experience.

Second Answer: Going into this novel, I really did hope that this woman was able to integrate into Detroit without joining a bunch of gentrifiers who see the opportunity to find a cheap house and fix it up. The synopsis focused on community, but it was so inwardly focused, the community largely ignored. Detroit NEEDS people to live there if it’s ever going to survive, but does that mean Detroit, the historical, unique Detroit, will turn into another large city with yuppies on bicycles opening breweries and organic gluten-free bakeries?

I like that you’re comparing numbers on how much it costs to live in Brooklyn vs Detroit. What the author suggests is that Red Hook was expensive to begin with ($2,000 per month in rent) and then became more expensive as touristy people moved into the neighborhood and drove rents up. I think she and her husband could no longer afford it. Then, she did the same thing to Detroiters, followed by a self-pitying conversation during which she asks herself if she’s the bad guy (though she doesn’t point out the connection between Red Hook and Detroit herself, as if she either doesn’t realize it’s the same thing or doesn’t want to draw attention to it). I’m not sure what made her life circumstances so different other than she got a job as a journalist. Maybe her husband made more money? I had this feeling that the author saw herself one way from when she was a kid and didn’t lose that image of herself even when her circumstances changed.

LikeLike

Bah! I knew that, too. My heart kept telling me, “Oh yeah. She definitely went to Notre Dame for both degrees, say that. It will make her happy you remember.” And my brain was like, “Um. Wait. Is that? … Oh, too late.” Regardless, this makes more sense to my brain now. I’m sad there weren’t more classes focusing on the black experience when you attended undergrad. Perhaps there are more now? I know there are more at my alma mater.

It’s weird watching all of America’s cities quickly becoming identical. Honestly, I blame the internet. It’s so much easier for trends to pop-up on one coast and be on the next coast by the end of the day. No one builds things to last any longer. Instead, they build high-rise apartments which they expect will last 20 years at the most. And, due to internet sales, Mom & Pop stores and restaurants are vanishing. I want diversity! I want each city to have a feel and an expectation. I don’t want cities to lose their identities…

It’s so weird to me that Haimerl wrote the whole book and completely ignores the parallel of what happened to Red Hook and what she is doing in Detroit. That’s basically the implied thesis! So, what is her thesis? Don’t bully me? Sigh. I don’t want to pick on her, but I’m frustrated. I just don’t know what the point is in reading this book.

Regardless, it’s hard to lose the vision of the person and status and representation you had as a child. It’s a part of your life for 16+ years before you leave out on your own. But the only way to see how your world has changed is to step outside of who you expect you are and examine your experiences. Obviously, Haimerl did not.

LikeLike

Your so smart; I love your response. I feel like I’ve read a lot of books that lack a thesis lately. It’s exhausting. I really liked Madison; everywhere we went feel like it’s own place, especially the pie diner. Here’s the breakdown: I went to Central Michigan University for undergrad, finished in 3 years, then started to do a master’s degree. Right after, I went to Notre Dame and did an MFA. Notre Dame lacked a lot of classes about black folks at the time. I would click “Africana Studies” when searching for courses, and there would literally be nothing offered. I took loads of Africana courses at CMU: film, history, literature, etc.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes! This is why I love Madison. While I dislike being so far away from my family, Madison feels unique. Yes, you can find some chain restaurants and we have three malls, but most of Madison is quirky. There’s more stuff to do outdoors than indoors! If you had come when it was warmer, we would have done a bit more of the creative outdoorsy stuff.

I’m glad you had an opportunity to explore Africana at CMU, as it interests you so much. Did you have to specialize for your Notre Dame MFA? If so, in what?

LikeLike

I went to Notre Dame specifically for the fiction writing program. However, you have to take two lit classes per semester, too. Most of them were on old books or authors–Proust, Victorians, etc. Not a lot of diversity. They started heading in a more diverse direction as I was getting ready to leave, and it’s gotten better since. There is actually a chair of the Africana department who started a book club. Funnily enough, his name is Page, too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is not a coincidence. 😉 Do you participate in the book club?

LikeLike

I’m not sure if he still does it, but I went twice back around 2013. We read The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks and Parable of the Sower.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve read The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, but I haven’t heard of Parable of the Sower. Would you recommend it?

LikeLike

It’s post-apocalyptic, and you almost get that feeling like in a zombie story where everybody’s trying to move to someplace safe, but they don’t really know where that is. That’s not to say that there are zombies in this book. Also, after I read it I learned that it is part of a trilogy, but I only read the first book. I would maybe start with Kindred instead. The author is Octavia Butler.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh, Kindred. I’ve been trying to figure out when to read this. I’ve been told it might unnerve me… But that isn’t a reason not to read it. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Mmmm. I thought this seemed like it would be an interesting read but it seems a little distasteful really. Unlike the course you took which sounds brilliant!

LikeLike

I was totally bummed. I’ll have to find better Detroit books. I also got an anthology of poetry, fiction, and essays during that same shopping book-buying experience. I was in a Michigan bookstore, so I’m not surprised they had a Detroit selection.

LikeLike

I live in Cleveland, Ohio, and this happens here as well. Although there are “pockets” of different communities, I happen to live in one where I’m the “wrong color.” So, we stay indoors primarily to keep my daughter away from harassment and, well, us from harassment. We want to move away, of course. But gentrification is really bad just as anything else over the top is.

LikeLike

I’m sorry you are harassed where you live, Jen. Does your daughter have some good friends at school?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, the trouble she has isn’t that she is white, she identifies as gay. Or lesbian. So she gets a lot of harassment for that. Not as much this year, but still.

LikeLike

I’m always wary of gentrification – it’s always privileged people ousting the original, less advantaged residents in the end. She sounds like she needs a dose of reality. Over here, middle class does tend to mean quite wealthy, while our working class tends to be what you guys call middle class. She sounds pretty wealthy to me, and I do dislike wealthy people who boast about how poor they are… and who live in their little privileged ghettoes…

LikeLike

And gentrification isn’t even about race in most places, but with Detroit it really is. We used to have a middle-class filled with people who have things: washers, dryers, new cars, a home. The middle-class in the States is so decimated that it’s basically anyone who isn’t homeless but would be destroyed out by a debilitating car accident. They keep up on the bills but are always worried about them. It’s ridiculous. I’ve heard Edinburgh was hit hard by gentrification, but used to be a working class place. Does that sound right?

LikeLiked by 1 person

There were always ‘posh’ areas of Edinburgh but also some really rough areas. Since the Scottish Parliament was created there in 1999, the city has become full of politicians, civil servants and everything that goes along with them, so there’s been a lot of gentrification and house prices have gone sky-high…

LikeLike

Oh, wow, I didn’t know that.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great review Melanie, class analysis spot on. The middle class in Australia is still the class that has things, though some of the working class earns more or less the same – say $100,000 per year – and has the same things. It’s the wealthy that moan about how poor they are that get up your nose. Not sure you can stop gentrification but certainly don’t feel sorry for the author who “appears white” and doesn’t seem to be able to acknowledge a. that she’s in a Black city; nor b. that the rebuilding/repopulating of Detroit might also be a chance to try new paradigms in Black/White shared spaces.

LikeLike

The interesting thing about Detroit is that it used to be largely a white city. When all the automotive companies offered good paying jobs, black folks from the south moved up north. That’s where you get things like the organizations that meet black folks who just arrived at the train station, who want to clean these new people up, so to speak, so that they represent the race in a “civilized way.” As a result of white flight, though, the city has become a largely black city. These dynamics have shaped Detroit, and I think as long as people respect that and fit in with a neighborhood economically and full if respect, then it doesn’t matter what race they are, so long as their location choices don’t result in little racial ghettos, like the one the author lives in.

LikeLike

“appears white”??? LOL was this book edited? Feel like that should have been caught in the first draft or so.

LikeLike

I know, lots of laughing at her dodging techniques. She’s silly.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think I’m confused as to why this book even exists. I mean, great for her and her husband that they bought this house and fixed it up. But if she’s not even going to use this as an opportunity to dig DEEP into race and gentrification and redlining and white flight then why bother even writing it??

LikeLike

Money? Attention? So people get more interested in her journalism? I saw on Goodreads that some people just can’t resist a home remodeling story.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Your class sounds amazing! I love being able to explore the history of a place and its people through the years.

LikeLike

It was the first history class I took in college. I ended up taking another class with that same professor, one on Civil Rights. It was so much bigger than Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X. There were a lot of small groups that really made things happen that we don’t learn about in school, probably because it’s so much information.

LikeLike

Your last line just made me laugh out loud. It very much sounds like this woman doesn’t want to acknowledge her white privilege. Even in California, 3500 a month would get you a pretty big home. I get that places in NYC can be expensive, but if you can afford rent that high, you’re probably not doing too bad. I’m rubbing my temples just reading your review, so I applaud you for finishing this one.

LikeLike

Thanks, Alicia. At first, I was lulled into contentment by her memoir. It was interesting, and I kept waiting for her to become this community builder she sold to readers. But the book gets more and more problematic. I was telling my friend Charles about this memoir because he has family in Detroit, and we were both laughing because privilege doesn’t mean feeling bad, it means being aware. People get weird because they suddenly think they’re required to apologize for their existence.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This sounds like an infuriating book and I’m impressed that you finished it! I think it would have gone to a charity shop about three chapters in if I’d tried. Or out of the window.

The class stuff is interesting. Class is such a complicated combination of financial and social factors, and even though I am now pretty well-off, I cannot shake the feeling that in my bones I am working class – it feels like a really big part of myself to relinquish. It certainly sounds like she is not just middle-class, but actually very wealthy – did she grow up poor, and is just having trouble adjusting to it? But then I guess she wouldn’t be so defensive – she sounds like she knows she’s part of the problem and is just in denial about it.

Great review!

LikeLike

Thanks! The author grew up poor and always sees herself in that context, despite being in her 40s. I think what the author doesn’t understand, or doesn’t appear to understand based on her memoir, is that being well off or white doesn’t mean she has to feel bad, it means she needs to be aware of how her presence may not fit with what’s around her. The people in Detroit likely won’t see her as a Detroiter (which she so desperately wants). They’ll see her as an outsider who came in and made Detroit living look relatively easy. They’ll see her as a white woman changing the demographics of Detroit, especially since she moved into an all-white neighborhood. And she needs to be aware of her impact on others and why they feel like they do.

LikeLike

[…] A main character you nope and who drives you crazy. Amy Haimerl in her own memoir. She’s not a character, but she’s definitely burying her head in the […]

LikeLike

[…] then I’ve been trying to keep up on books about Detroit. Recently, Detroit Hustle failed to impress me. I had higher hopes for A Detroit Anthology, edited by Anna Clark, because she […]

LikeLike