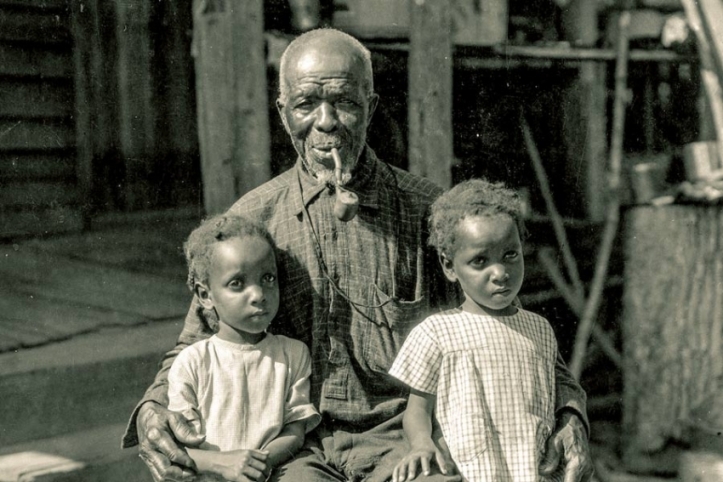

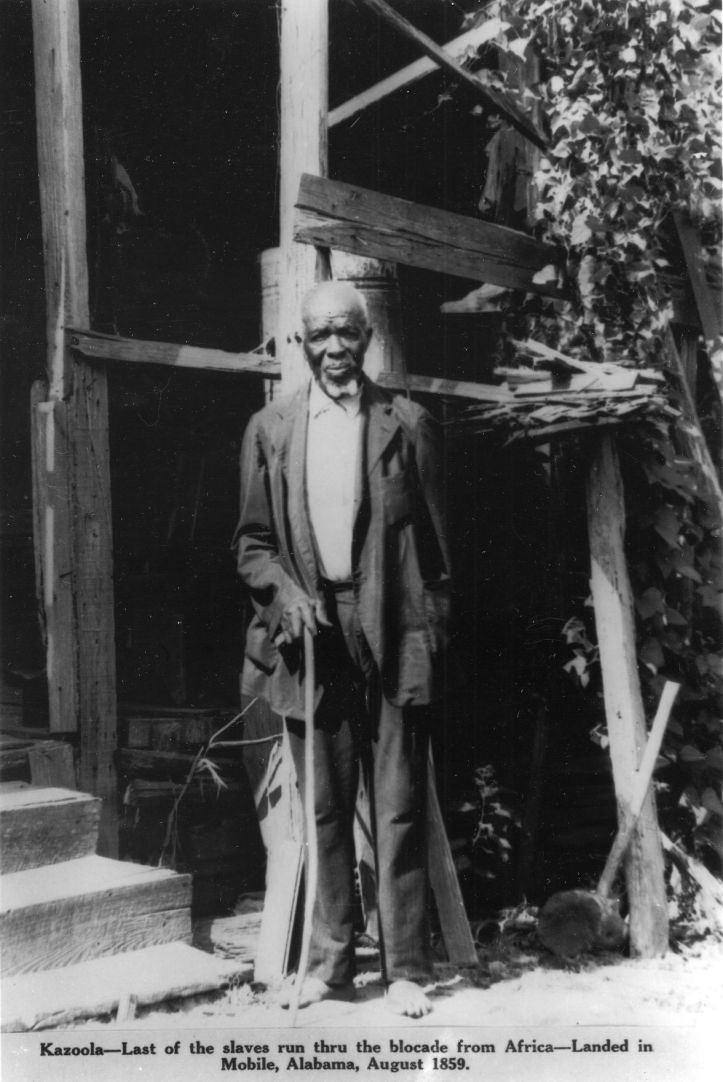

Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo” by Zora Neale Hurston is a nonfiction work written after Hurston interviewed the last living slave who had been brought over from Africa. Keep in mind that while slavery was still legal in the United States, the slave trade from Africa was not. Hurston’s subject, born around 1841 as Oluale Kossola in West Africa, came to be known as Cudjo Lewis in the United States. He was living in Alabama when Hurston first met him in 1927 — when he was around 85 years old!

Kossola came from a peaceful tribe that trained him as a soldier for defense purposes only. But the nearby Dahomey tribe, known for starting war so they could capture prisoners and sell them to American slavers, took Kossola from his home when he was 19. Hurston listens patiently and plies Kossola with fruits and meats as he tells how he grew up, was forced to the United States, lived as a slave for six years, and then had to recreate himself after the Emancipation Proclamation. Kossola always, always wanted to be back in Africa, even as an old man. Always.

Like other Zora Neale Hurston books I’ve read, scholars are so eager to add their two cents that the “extras” get to be too extra. Kossola’s story is 94 pages. The book is 171 pages. You get the following (if you’re interested):

- A foreword by Alice Walker, who rediscovered Hurston in the 1970s and brought the writer back into the public eye.

- An introduction by editor Deborah G. Plant

- Plant’s note about her edits

- A preface by Zora Neale Hurston

- An introduction by Hurston

- The actual text about Kossola

- An appendix

- An afterword by Plant

- Acknowledgements

- A list of the people who founded Africantown in Alabama

- A glossary

- End notes

- A bibliography

As you might expect, much of this is repetitive. How could it not be?? I recommend that you flip through the book first to see what’s in it lest you not see the glossary until the end, for example. There are a few reasons I do encourage you to read the whole book, though. The editor’s section on “Trans-Atlantic Trafficking” explains how slavers got to Africa and why they kept doing it after it was outlawed. Africans, like the Dahomey, were a partner in this slave trade. Kossola alone would not have this contextual information.

Furthermore, the editor notes that Zora Neale Hurston does not fictionalize Kossola’s story. She tells it in his “vernacular diction, spelling his words as she hears them pronounced. Sentences follow his syntactical rhythms and maintain his idiomatic expressions and repetitive phrases.” Finally, Hurston’s quotes and paraphrases from other sources could be incorrectly cited, so the editor cleared up the documentation. Readers are doubly assured, then, that this is Hurston’s book and Kossola’s story — not a watered-down version of some editor — which had been a big concern of mine.

Prior to completing the manuscript to what would become Barracoon, Hurston wrote an article about Kossola. I bring this up because much of the work was plagiarized. Hurston’s most notable biographer, Robert E. Hemenway, notes that “Of the sixty-seven paragraphs in Hurston’s essay . . . only eighteen are exclusively her own prose.” I was disappointed to read this, but I knew that Hurston’s career as an anthropologist made me feel hesitant hesitant for other reasons. However, the biographer notes that Hurston never plagiarized again.

Another Hurston biographer, Valerie Boyd, noted that the person who hired Hurston to write the article did not pay her in full, so she kept all the “juicy bits” of Kossola’s story for a later project — which became Barracoon. I note all of this because I am interested in the controversy that always surrounded Hurston, for her whole adult life. Each time I get more controversy, I learn more about the person behind the pen.

Kossola’s story reveals a traumatized man who doesn’t always want to talk — and Hurston respects that. He would say, “Doan come back till de nexy week, now I need choppee grass in the garden.” If you struggle to read dialect, get this work as an audio book. The quote you just read is how almost the whole of Kossola’s story is written. Personally, I love the musical cadence to Kossola’s speech, and I even caught myself adding “ee” to things I said at home (e.g. “scoopee the cat box”). I’m not sure if this makes me a bad person.

He’s an interesting storyteller; Kossla gets all the facts out and then ends with a sentence that seriously hurt in my chest. Here’s an example (emphasis added) from when the Dahomey tribe attacked and cut off the heads of some and captured others in Kossola’s tribe:

When I see de king dead, I try to ‘scape from de soldiers. I try to make it to de bush, but all soldiers overtake me befo’ I get dere. O Lor’, Lor’! When I think ’bout dat time I try not to cry no mo’. My eyes dey stop cryin’ but de tears runnee down inside me all de time. When de men pull me wid dem, I call my mama name.

Okay, I might be crying again. He doesn’t just share his life’s events, Kossola discusses the differences between Africans like him and African Americans born in the United States. When the African women are whipped on the plantation, they take the whip away and lash the overseer with it! When the Africans get Sundays off, they dance. But the African Americans tell them they are savages and laugh. Whereas I’ve read many stories about African Americans struggling to create communities post-emancipation, Kossola and other Africans sit down, figure out how to save up money, buy a piece of land, make laws, and build a church and homes themselves, together. They call the place Africantown.

Kossola notes that when the African Americans call them ignorant, the Africans build a school because then the county has to send them a teacher. He says, “We Afficky men doan wait lak de other colored people till de white folks a gittee ready to build us a school.” It was educational for me to read how an African man perceived differences in the behaviors of former slaves. According to Kossola, African Americans were quick to name call and laugh at Kossola and his group.

I recommend Barracoon, and not just if you’re a hard-core Hurston fan. The fact that Barracoon was finally published set Zora Neale Hurston fans into a tizzy. If you don’t know the history of why Hurston’s manuscript wasn’t published for 87 years (Hurston herself has been dead for 58 years), check out this New York Times article.

I keep hearing that I ought to read this one, and your review makes me think that all the more. I like the idea of a story told in cadence, like an oral history is told. And this story, especially, sounds as though it’s more effective told that way. And what insights into life at that time. Lots of fascinating and powerful stuff, even if you don’t read all of the additional information.

LikeLike

I like the fact that Hurston wrote down Kossola’s story as she HEARD it from him. Therefore, she’s not really correcting spelling or anything like that. Apparently, his name, Kossola, has several spellings based on research others have done. This book also led me to buy Dreams of Africa in Alabama: The Slave Ship Clotilda and the Story of the Last Africans Brought to America by Sylviane A. Diouf, which follows the group Kossola was with as they were kidnapped, sold, crossed the Middle Passage, etc. Diouf, to my knowledge, does all research (Kossola died before she was born) to piece together the history. I think it will be a good companion piece to Barracoon.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is certainly a work to look up in the library, and read the bits that are actually about Kossola. The life and times of people who might as well be aliens from another planet, they lives they led compared to ours, today. It’s still terrifying and shocking what people do to one another!

LikeLike

And this book certainly should be in the library because it’s all over the news. I bought it because I have all of Hurston’s work 🙂 I’m a bit of a fan! I would recommend also reading Plant’s introduction because she gives some context that Kossola wouldn’t have had.

LikeLike

I really enjoy autobiographies. It’s getting those glimpses into people’s lives, learning about their struggles as well as personal victories. I am really intrigued by this book, your review really piqued my interest. It will be a great opportunity for me to learn more of this topic as well, thanks!

LikeLike

Thanks, Vera! They should have it at your local library because it’s publication was such a big deal. Hurston also has her own autobiography, if you’re interested.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am interested and will definitely be checking my library out to see if they have a copy of both of those books. Thank you. 😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

First of all: I LOVE THE NEW BANNER. It’s sooooo fun! Ach. Why are you so brilliant?!

Ever since I read Their Eyes Were Watching God (at your recommendation, I might add…) I knew I needed more Hurston in my life. Barracoon sounds perfect. While I’d love to listen to the audiobook for obvious reasons, I don’t know if I could get through all the “extras” when listening. Plus, the audiobook is published by Blackstone Audio. Not encouraging. XD

Is there a biography of Hurston you’d recommend? You’re always linking out to amazing articles. But I’d love to sit down and learn as much as I can in a single sitting. I’m not great at internet research or, uh, focus.

LikeLike

I reviewed Hurston’s autobiography, but it’s well known that she was a big ol’ liar (one of the reasons I love her), so I recently acquired the most referenced biography of hers, written by Robert Hemenway. There was also an anthology of her letters published recently, which I also acquired but haven’t yet read. I’m wondering how honest she is in those. Again, she’s a liar. I would say read her autobiography, enjoy what she has to say, but remember that she’s pandering to certain audiences (her white patron, for one).

Also, super secret squirrel delivery: I had my husband design my banner. He’s a tech guy.

LikeLike

Fascinating post about what sounds like a fascinating book! This is why I get so fed up with the whole black/white thing – black people were just as horrible to their fellow black people and white people were just as horrible to their fellow white people. Couldn’t we just forget colour and think in terms of right and wrong?

LikeLike

Color issues are so institutionalized in the U.S. that people can’t even see it. Therefore, asking that people treat each other as individuals doesn’t really work here. I’m not sure I wish it would work that way yet because those very institutions have set black communities back so far that to simply make the bar equal wouldn’t actually equalize things. For instance, more African Americans are imprisoned, but changing police practices wouldn’t fix that. Black families are segregated into poor communities with poor schools, but fixing housing wouldn’t fix generations of education inequality, etc. For reasons like these, we’re never going to stop talking about race in the States.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You have to love Hurston and her work. We won’t ever understand who we are if we just go along with mainstream (ie. white, male) histories. I think you are more than ‘a bit of a fan’. You are genuine enthusiast educating both your students and your friends out here in the blogosphere.

LikeLike

The frustrating AND best thing about Hurston is that she was such a liar! Lying makes for great stories and a self-crafted life, but we really don’t know as much about Hurston as we think. She changed her birthday to impress young men, she pandered to white patrons to keep funding her, etc. Thanks for your kind words. I have more Zora in my pocket, so she’ll be back again at Grab the Lapels!

LikeLike

Hmmm I could see how reading that dialect would be difficult at first, but I think you’d get used to it. I’m curious how the audio book would be-i don’t think I’d like the intrusion of someone narrating, it would feel too artificial I think? Anyway this was a great review, very fascinating stuff.

LikeLike

A few lines come from Hurston, but most is Kossola talking. The “ee” was easy to pick up, but then he throws in a “nexy,” which I think is hard to say because I’m not sure how it sounds (there’s no T). Also, Hurston wrote, but Kossola is a man, so I hope the narrator is a man who catches the rich sound of Kossola’s diction. Someone like Paul Robeson….who is super dead.

LikeLike

I didn’t know there was such controversy surrounding Hurston. Regardless, this sounds fascinating. Sometimes when I read books where the protagonist has a strong accent, I read it as such in my head or even aloud and it takes a while for me to shake it off.

LikeLike

She lies a lot, and there are certain conventions in anthropology that she doesn’t always follow. However, there are different schools of thought in anthropology, so it all depends on where you’re coming from. I talked to an anthropologist when I reviewed Mules & Men by Hurston, and she said some people are just observers while others insert themselves into the narratives they see. If you insert yourself, in some way you could be changing the culture you’re trying to capture.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s an interesting way of looking at it. I personally don’t think I’d be able to remain entirely independent.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great post! This sounds SO interesting!! I love that it’s published in Kossola’s dialect, and sad that the publishers didn’t like that when she first wrote it. I’m glad she refused to change it.

LikeLike

Me too. I just wrote on your Twitter that this man was so homesick from age 19 when he was kidnapped to his death in his 80s that he had hoped that Hurston writing down his story might mean that someone in Africa would hear it or read it and remember his name. Devastating.

LikeLiked by 1 person

*sob*

LikeLike

Oh! And that quote is heart-wrenching!

LikeLike

Yes. It hurts my heart.

LikeLike

Oh the sentence about the tears running down on the inside- stunning. So interesting, thank you for sharing not only a taste of the work itself but also the historical context and Hurston’s process. The story of the story, fascinating.

LikeLike

You’re welcome, Jennifer. If you only read Kossola’s story, it’s a quick read. I’ll bet your library has it.

LikeLike

“I call my mama name.” Heartbreaking. I want to read this one. Apart from reading your post, I don’t know much about it. It sounds like an important reminder of how ineffective laws can be (such as the abolition of the slave trade in 1807) when the people in power don’t care to enforce them.

LikeLike

The slave ship was actually running from the law, so they sank it. The law was being enforced, but they weren’t caught, especially since tribes were helping capture Africans to sell. If you just read Kossola’s story, it’s fast.

LikeLike

That quote is really heartbreaking. I might get the audiobook of this as I really struggle to read dialect (even dialects I’m familiar with, which I am not with this), so thank you for suggesting that!

LikeLike

You’re so welcome! I’ve had other readers mention that the books I recommend are hard to read, so I’ve been keeping that in mind.

LikeLike

I’m on hold for this at my library. Great review! I am gonna check out that NYT article because I was wondering why this hasn’t been published until now. Thanks!

LikeLike

You’re so welcome! I hope it’s not a horribly long hold. If you’re super busy, just read Plant’s introduction and Kosolla’s part.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This sounds like a fascinating bio! I’ve only read Their Eyes Were Watching God by Hurston. I didn’t realize she wrote nonfiction… I also didn’t realize there was so much scandal surrounding her. I’ll have to check out the article.

As soon as you said Hurston spells out Kossola’s words as they were pronounced, I figured this would be a better experience in audiobook format. I’ve read books where the character’s words were spelled out this way and I find it can be hard to follow at times.

LikeLike

*spells out

LikeLike

There is quite a bit of dialect in Their Eyes if I remember correctly. I’ve both read and listened to that novel. Hurston actually wrote loads of books, but because teachers assign Their Eyes, I think that’s where most people start and finish.

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] stories have been changed, but one flaw with re-published Hurston works is overabundance of voices, making the “extra information” tedious — and sometimes full of spoilers. I skipped all superfluous additions to Every Tongue Got to […]

LikeLike

[…] it through her own voice made me feel distant from the subject. By comparison, Cudjo Lewis in Barracoon explains his life in his voice, and Hurston captures him fully. As much as I love Hurston, if […]

LikeLike