Content Warning: attempted suicide, casual sexism, and some use of racial slurs

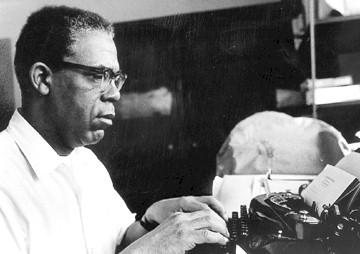

Wrestling With The Muse (Columbia University Press, 2003) by Melba Joyce Boyd is a mishmash of memoir and biography about one of the most important publishers in the United States. Because most people have never heard of Broadside Press or its founder, Dudley Randall, I’m going to give you a longer synopsis and then review a few aspects of the book.

Dudley Randall was born in 1914 and died in 2000. His grandparents had been slaves, which should remind you slavery wasn’t that long ago. When Randall was 6, his family moved to Detroit where he lived the rest of his life (with one or two brief moves). In 1910, Detroit’s black population was small at 5,741. But the urge to escape the South caused a mass migration to Northern cities, such as Chicago, Cleveland, and Detroit. After a wave of migrants hit Detroit, the black population swelled to 40,838! Note that both North and South have rampant racism, but in the South black people were more likely to be murdered. In Detroit the KKK had over 32,000 members, and in under 18 months police killed 25 black people.

Randall served in WWII and wrote poetry during his service. During WWII, another great migration brought more black people to Detroit, and the population reach around 500,000 black men, women, and children. Randall graduated from Wayne University (now Wayne State) in Detroit in 1949 and attended University of Michigan for a degree in library science. Meanwhile, times were tumultuous in Detroit. There were famous race riots and Black Bottom (a black neighborhood) was bulldozed, causing 2,000 black families to lose their homes. Randall was married 3 times, but remained married for over 40 years to his 3rd wife. Randall could be shy, moody, introverted, and very quite. He had the perfect demeanor for a librarian.

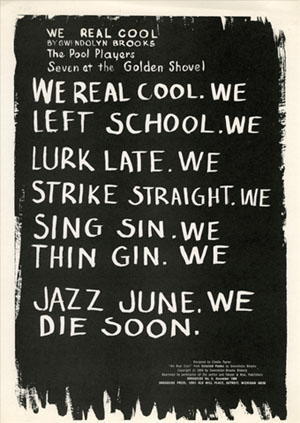

Randall’s work gained recognition in the 1960s, even though he wrote most of his poems during the 1930s-1950s. This would make a difference in how people perceived him. In 1963, Randall’s arguably most famous poem, “Ballad of Birmingham,” about the girls killed in the church bombing, was published. A folk singer wanted to set it to music, and because Randall was worried about his rights as an author, he “printed the poem as a broadside and copyrighted it as a Broadside Press publication.” And that’s how the most important black press started. *mind blown*

Because 1960s activism was dominated by young people, Randall, then around 50, was a different type of poet than Black Power crowd. He respected form and the great white poets everyone reads in school. The Black Arts Movement of the 60s, a literary voice of the Black Power Movement, was dominated by anger, hypermasculinity, and the absolute rejection of whites. Their poetry ignored form, was mainly free verse, and was always about race. Randall argued that good poems are more important than race poems, which put him on the outside.

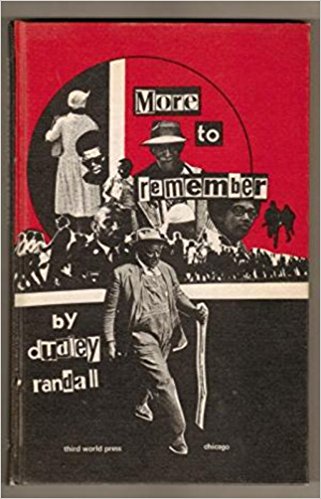

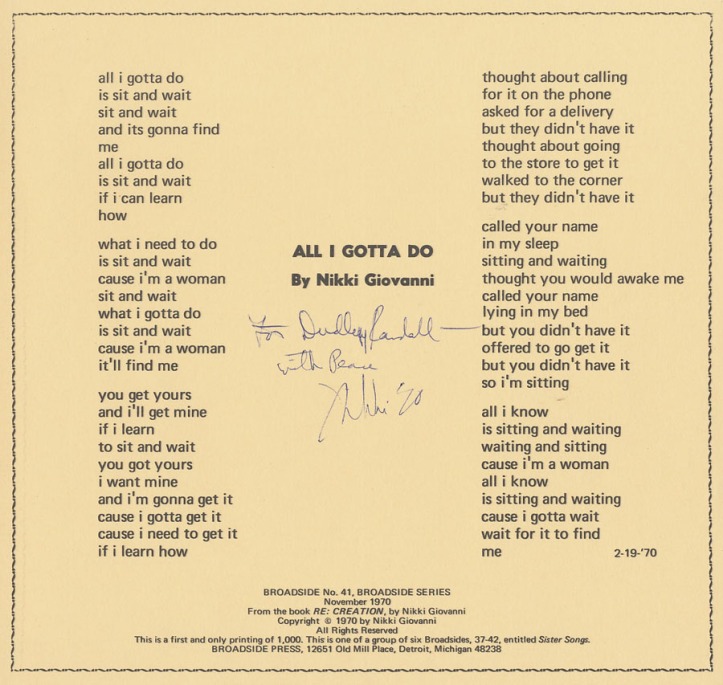

However, established presses were not publishing black poets, and Randall did, regardless of his feelings about their politics. He established the careers of powerhouses like Etheridge Knight, Nikki Giovanni, Don L. Lee, Audre Lorde, Gwendolyn Brooks, and Sonia Sanchez and edited and published a collection of poems from various contributors called For Malcolm after Malcolm X’s murder. Randall wrote, “A neighbor told me that he saw a worker on the production line of an automobile factory with a copy of the anthology For Malcolm in his hop pocket . . . . black people were reading poetry and finding it a meaningful, not esoteric, art.”

While a few black poets did get publishing contracts with large presses after they were established, many abandoned those contracts and stuck with Broadside Press, even if they would have less marketing, because they believed in what Randall was doing. Broadside Press books cost $1, with 10% going to the writer, so “students, young people, and poor people might be able to afford them.” But after 10 years and over half a million books printed, Broadside Press had to be sold. Randall focused on poetry more than money and was $30,000 in debt.

In the 20 years before Broadside Press, only 35 books by black poets had been published in the United States. In 9 years, Randall published 81 books and a critical poetry studies series — all on a shoe-string budget in an office that used to be a burger restaurant.

After Broadside Press was sold, Randall entered a deep depression for 3 years and was stopped right before attempting suicide. Randall felt like he failed. After 3 years, he then wrote a surprising bawdy poetry collection. Gwendolyn Brooks scoffed at Randall writing a love poem shortly after a race riot in Miami, saying “So you’re in that bag now.” Randall scolded in poetry those who told him he had to write race poetry, writing:

I repeat, A poet is not a jukebox for someone to shove a quarter in his

ear and get the tune they want to hear,

Soon after, he got ownership of Broadside Press back due to some clause he forgot about in the contract when he sold it. The press didn’t last much longer, but regaining ownership seemed to encourage Randall further out of his dark depression. Randall was awarded the 1986 NEA Life Achievement Award, 1981 Poet Laureate of Detroit, and many others. He still thought of himself as a nobody.

The story of Dudley Randall’s Broadside Press makes for an interesting book. The Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s-1930s got a lot of attention, so people argue that Broadside Press became the bridge into the Black Arts Movement. Wrestling With The Muse includes B&W photos of famous poets with Randall, and those poets perspectives are included and quoted. I was surprised how easy people would change their minds in the movement. Don L. Lee, who Randall helped rise to fame, later said Randall himself wasn’t a black poet because Randall saw white people as human. At Randall’s funeral, Lee said Randall was one of Lee’s “true heroes” and compared Randall to Malcolm X.

What you really see is a clash of ideas, which is never a bad thing. Randall frequently gathered with poets to discuss ideas. Later, some of the black women Randall published felt hesitant about Randall because he didn’t take to the feminist movement well. He thought women should appear and behave traditionally, though he respected their intelligence.

I didn’t worry about author Melba Joyce Boyd’s accuracy in Wrestling With The Muse even though she was a friend of and mentored by Randall. In the introduction, she explains her 3rd-person POV is used to distance herself, but uses 1st-person when she was present for something, like Randall’s funeral. Boyd used audio and video interviews, though those were not always helpful due to Randall’s shyness; however, they were effective in “…determin[ing] any inconsistencies and to clarify Dudley’s recollections.” Although Randall destroyed many papers and diaries during the three years he was severely depressed after Broadside Press was sold, Boyd used essays, interviews, and correspondence written by both Randall and his friends, family, and colleagues. Thus, I do not worry about the author’s bias. At times, she is critical of him in a fair way.

There several frustrating typos and places where it’s hard to tell who’s being quoted. Randall’s diary may be quoted in italics and then the next paragraph is not in italics, but it’s still Randall’s voice (perhaps an interview?), which can be confusing.

However, Wrestling With The Muse by Melba Joyce Boyd is worth the read. You can skip the chapters in which Boyd analyzes Randall’s books of poems, to be honest, especially since she doesn’t always include entire poems or excerpts (likely due to copyright issues). But seeing the changes poetry underwent over an 86-year lifespan gives you a fantastic idea of race relations in the U.S.

![lee] lee]](https://i0.wp.com/grabthelapels.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/lee.jpg?w=282&h=424&ssl=1)

Is this the memoir we spoke about on Twitter?

Randall’s life does sound fascinating. Especially how he supported poets whose political views he disagreed with. How did that dynamic work exactly, I wonder?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think Randall really believed in good poetry. So, even if the theme wasn’t something he agreed with, he would publish the book if it was good poetry. I was surprised how Don L. Lee was such a flip-floppy friend. Melba Joyce Boyd mentioned LeRoi Jones AKA Amiri Baraka many times in the book. He wasn’t published with Broadside Press that I remember, but he would come around. He was another angry poet who felt white people should be excluded from everything, and Dudley Randall didn’t. He felt black writers should make their own success and stop blaming white people for not paying attention to them (which is why he started the critics series to analyze and review poetry). This is all right off the back of Malcolm X, who very strongly preached that separatism was the best way for Americans to move forward, as white people and black people naturally moved toward others of the same race. Thus, a lot of thinkers during the 60s were thinking about Malcolm’s ideas and integrating them into their own.

Yes, this was the book I mentioned on Twitter. In a couple of chapters, Melba Joyce Boyd analyzes Dudley Randall’s latest book of poems, but she doesn’t include any copies of the poems–or even excerpts. That was very dry. There is one other book about Dudley Randall that I wouldn’t mind reading, but I would have to buy a copy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for these insights, Melanie! I always learn so much from you. I did learn a bit about the Harlem Renaissance and American poetry in general while in college, bit that was never in much detail. So this is all very eye opening to me. Thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very interesting – thank you! I may have to take cover for saying this, but I do sometimes wish black people would write about something other than racism, immigrants about something other than the (usually negative) immigrant experience, LGBT people about something other than LGBT issues and discrimination. Actually, there probably are writers in each group who do, which would mean I would then be unaware of their background or personal circumstances, but I do think that authors have a tendency to push themselves into niches, and by doing so, actually accentuate difference and division. Not of course saying no books should address these issues, but the balance seems skewed at the moment… in my opinion, of course!

LikeLiked by 2 people

You’re not alone. Both Dudley Randall and Zora Neale Hurston, whose work I’ve read and reviewed a lot lately, did not want to be identified as black writers, but GOOD writers. The issue is that they were both alive in times when there were almost NO voices from the black community. Both, as a result, were given a hard time–publicly–for their opinions. Richard Wright, author of Invisible Man,wrote that Hurston was a traitor and a poor writer. It got nasty. Dudley Randall felt that he should be allowed to write a love poem because THAT is the black experience, too, but in the heated 1960s, just after the murder of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr., almost no one agreed with that opinion. Randall said he was black before he was a poet. His good friend said he was a poet before he was black, and that man was ostracized by many groups. Here’s the thing, though: by the 1970s, women–black and white–are pointing out that the race movement isn’t helping them. They’re still belittled, given no opportunities, etc. So the Black Arts Movement faded away because there was yet another faction. It’s hard to keep a big movement going when people break off into their own little groups.

LikeLike

Yes, I remember reading that about Hurston when I read Their Eyes Were Watching God, and I could also see where Richard Wright was coming from, though I felt he went too far. It is a difficult balance, but I’m not sure we’ll ever get past discrimination while people are so determined to “identify” as just one aspect of themselves, though I understand why they feel they need to do it. And yes, you’ve reminded me that I’m also very tired of women writers banging on about sexism… #badfeminist 😉

LikeLike

This is why I love reading your blog, Melanie– you are constantly opening my eyes to books and ideas I’ve never thought about or considered!

I’ve never heard of Broadside, which makes me sad. I *am* familiar with the poetry of Gwendolyn Brooks, Don L. Lee, and Sonia Sanchez. So I’m even more shocked this story is new to me. It just shows how little attention publishers can receive. Over the past year I’ve learned enough about publishing to know I really don’t understand it at all. Micropress, boutique, self-publishing… There is so much to learn.

It sounds like the stories of Dudley Randall and Broadside are completely intertwined. When Randall sells Broadside does the story continue to follow both or just Randall? Also, do you think the inconsistencies in editing are intentional to show where information might be quoted from different sources, or perhaps something else?

All in all, this book definitely intrigues me. I’m completely on Randall’s side about how POC poets should still be able to write what they want. It’s not always about race. While that matters and we need someone to confront and address these issues, I don’t believe that burden falls on every poet’s shoulders.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Jackie, don’t feel bad. Most people outside of Detroit have never heard of Broadside Press. There are only two books out there about Dudley Randall that I know of, and this is one of them. Most small presses don’t make it in the end, but Broadside survived in an impressive way, printing runs that are bigger than some publishers put out today. Dudley Randall was $30,000 in the hole with Broadside; many stores ordered copies and then couldn’t pay their bills because times were changing and the money wasn’t there anymore. That $30,000 was all owed to the printer. Since Randall randomly and almost accidentally started Broadside one day, his and his wife’s finances were all tied up in the press. If he didn’t sell, they could be ruined. I’m not sure why there was a weird clause in the contract that said ownership of the press reverted back to him after 5 years, but it did. During that time, the book followed Randall, so I don’t know how successful it was financially. The editing issues are really on Columbia Press, who released this book. When a typo occurs in a document that the author quotes, they put [sic] to show the typo is intentional. I’m not sure how it was that Columbia put out something with typos because they are a pretty stable press attached to a college.

FictionFan also mentioned that she thinks all poets should write what they want, regardless of race. I definitely get both perspectives, and because I’m white, I never fully declare that I think it should be one way or the other. On the one hand, a published poet has a platform and a microphone, so if he isn’t doing something to help his race–because at the time they’re being jailed, killed, kept out of decent house (which means poor schools) and can’t get decent jobs–I see where the immediate pressure is to do SOMETHING. On the other hand, limiting a human’s experience in any way is a type of impotence that renders a poet incapacitated from his true individual feelings, which may include race AND other thoughts.

As for your comment about publishers: because of the internet, there is a lot more a person can do.

Micropress: they usually put our a very small number of books each year (2-3). Sometimes they put out small books (physically, they are smaller in size and/or shorter in length, like a chapbook). They don’t print as many each run, either. Maybe 50-100. An example would be Tiny Hardcore Press, founded by Roxane Gay.

Chapbooks aren’t a type of press, but they are a type of book. They’re usually small and don’t typically have the same sturdy quality as a regular book. In this way, it reminds me of something that might have come out of publishing works like a broadside (the piece of paper, not the entire press). Chapbooks can be very do-it-yourself. Some small presses hand-make their chapbooks, so each is unique! I think this is cool. Chapbooks are frequently published by small presses, universities that run a chapbook competition, or even blogs that are used as e-magazines. An example of a university that runs a magazine AND a chapbook competition would be Iron Horse Literary Review through Texas Tech.

A boutique press typically only publishes certain kinds of books only. For example, Ellora’s Cave only publishes erotic fiction.

Self-published means the author’s book was not published with any type of publisher. Amazon makes this easy, now. If a writer can write, edit, format, and get a cover design for her book, she can upload it on Amazon. Some authors–even famous ones–are going this route because they’re tired of big presses having so much control over the work. Also, since self-published authors typically have no name/credibility of a press to back them up, their books are cheaper, so readers are willing to give the book a chance. Andy Weir’s famous novel, The Martian, for example, was first self-published because none of the big presses wanted it. The novel got famous thanks to readers, and it was bought by a big press.

A vanity press is when a writer or his/her friends start a press to publish themselves. I don’t like vanity presses. They make it sound like a press accepted and professionally edited and designed the book, but they haven’t. When you google the press name, you typically find nothing. I feel like this is deceitful, especially if you’re a blogger and have a “no self-published books” rule for review copies. Vanity press folks will pretend like someone else published their book, when really, they did and made up a press name for their own book. When I was accepting reviewer copies, I always googled a press before I said yes.

Indie press is a term people don’t use the same way. It used to suggest independent of the big New York presses, much like indie films are not connected to large studios in Hollywood. Now, some self-published and vanity press folks call themselves “indie” because they, too, are independent entities. I think indie sounds more reputable to some folks’ ears than “self-published.” There are “big” indie presses that you’ve likely heard of, like Coffee House Press, and there are small ones, like Shade Mountain Press.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh. My. Gosh. You just wrote me a blog post length response. That… I am just blown away! This is *amazing*. Thank you!

I appreciate how the books follows Randall and not Broadside– but the little bit of research I did showed that nothing really came from Broadside when Randall didn’t own it. And you’re right, that is a super strange cause! I want that sort of thing in all my contracts. 😉

I really struggle with the idea of needing to represent something because of how you look and where you stand. For example, as a practicing Jew, a lot of my friends expect me to take public action against the Neo-Nazism which has been popping up across the country. Perhaps it’s my privilege talking, but I don’t feel like I need to carry the weight of my people on my shoulders. There is certainly pressure to do something– as I am a professional public speaker– but it’s just not for me. I feel the same about poets. You shouldn’t have to share all the truths of the world you want to see and carry that burden if you don’t want to. That’s only your cross to bear if you choose to pick it up.

Wow. I just learned a TON about the publishing world. Honestly, that might be a great future post for you– help us plebs out! 😉 I love the idea of Googling the press before accepting a reviewer copy. That never occurred to me. I fully believe in supporting self-published authors, but there are probably some presses which I wouldn’t agree with for the reasons you mention above. I’ll definitely be doing a better job looking at the publishers now when I read, request, and purchase books!

Thanks for all the details. This helped a TON.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re welcome! Let me know if you have more questions.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh don’t worry, I certainly will. Right now I’m trying to figure out how to ask my librarians about micropresses. Last time I asked, the elderly volunteer didn’t know what I was talking about. At least now I know how to describe it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Micropress books don’t typically appeal in libraries. So often, they make it 2-3 years and then shut down due to lack of funding. The best way to get them is buy them straight from the press to support their work. Ask if they have deals on buying more than one book and they might work with you! I’ve done that a few times.

LikeLike

Very cool! Where did you hear about this book in the first place?

LikeLiked by 1 person

When I was an undergrad, I needed a history class to graduate. I was so, so tired of getting the same European/White American history that I find boring. It’s a whole lot of conquering/colonialism and remembering dates. I happened to find a grad class offered called “Black Detroit,” and I signed up. The professor tried to scare me off because it was a grad class and I wasn’t a grad student, but I stuck it out and ended up doing better than a lot of the others. We covered Motown, the United Auto Workers, politics, white flight, black migration, civil rights groups, store-front churches, Detroit riots (there is a movie about one of the riots coming out soon–called Detroit), publishing, housing, police brutality, race representation, etc. It was the best class I ever took, and history isn’t even my major, lol.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow that sounds amazing! Agreed that history class can be so boring when you are just rehashing the same events over and over…it’s frustrating that it’s hard to find other parts of history that are deemed “less important”

LikeLiked by 1 person

It just seems like a lot of white America and Europe want to go around and take other people’s stuff. Message received, high school history classes.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lol

LikeLike

This is a fascinating story! Thanks for reviewing this. I’d not heard of Randall before, sadly, although I’m familiar with many of the poets he published. I love how he wanted poetry in the hands of working people. It’s a shame that poetry isn’t more popular than it is – we’ve somehow been sold a notion of it being inaccessible and “too hard” or “out of touch” with human experience.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes! No one else has mentioned that part. I love that he priced the books for the poor and that he wanted poetry that said something. I took a poetry class in college, and the teacher asked why we would write a poem about something people can go see. He said, “Why write a poem about the beach when you can go to the beach?” We wrote such trivial, nonsensical junk in that class. We would even do things like put words in a hat and draw them at random, and those were our poems. And I think that’s what’s happening with a lot of poets–they’re afraid to use traditional forms because it seems “old” or “silly.” If I had a nickle for every time I heard someone say they would never read or publish rhyming poetry… My response is, “Well, get use to being forgettable!” There is even a lot of fiction out there that is trying so hard to escape that traditions of storytelling–even plot!–that we’re getting more and more experimental stuff that doesn’t speak to me on ANY level.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Mary Oliver is one of my favorite poets and she writes about things people can see and smell and feel and hear and touch – mostly nature and animals – and it gives me such a spiritual feeling when I read it. I believe poetry is meant to speak to our souls and our real lives, connect emotionally to the universal commonalities. But that’s just me – your old professor would think I was “silly” I guess!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, he also got let go for plagiarism, so we won’t listen to him 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating review of subjects – printing, poetry, black politics – all completely outside my experience. And the comments too, great reading all the way down!

LikeLiked by 1 person

People definitely asked good questions, and I was too eager to answers, as you can probably tell by the length of my responses.

LikeLike

This was absolutely fascinating to read! I had never heard of Dudley Randall nor Broadside Press before reading this. I find it very sad that Randall never really viewed himself as successful despite the fact that Broadside Press published over 80 books by black poets in 9 years where only 35 had been published in the 20 year span prior. It sounds like he truly cared about the poetry, but was often faulted for not being more political or addressing race issues in his poems. Did Broadside Press only publish poetry?

LikeLiked by 1 person

They only did poetry and criticisms of poetry. That is such a rare thing to do. Everyone focuses on prose, won’t publish poetry, and then claim poetry is dying.

LikeLike

Oh wow, this book sounds fascinating! I’m not familiar with any of the poetry or this press, but what you’ve posted here is so beautiful. I really need to read more poetry, and this sounds like a fascinating read!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think a lot of the original books are quite rare, though you can find the poets online.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“A poet is not a jukebox for someone to shove a quarter in his

ear and get the tune they want to hear” Too true. And I agree with the women though, I might not have taken to him well if he hadn’t joined the feminist movement. Great review.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!

LikeLike

[…] Wrestling with the Muse by Melba Joyce Boyd […]

LikeLike