Author: Tomboy: A Graphic Memoir

Author: **Liz Prince

Published: by Zest Books in 2014

Thirty-one-year-old comic artist Liz Prince shares her history as a tomboy. She begins with her tantrum at age three when she didn’t want to wear a dress. All through elementary and middle school, Prince is tormented. No one wants to play with her, she hates all things girly, and classmates begin to question her sexuality. High school is a huge problem area until Prince finds a group of friends who are more open-minded. While the narrator (Prince at 31) could interrupt the narrative more regularly, Tomboy is a graphic memoir that will have readers nodding along in recognition as Prince analyzes what it means to be a tomboy in a society that tells men and women how to be from birth.

For me, a good memoir is analytical. A few weeks ago, I reviewed Alison Bechdel’s graphic memoir Fun Home and discovered that it was the most analytic memoir I’d ever read, in graphic form or otherwise. Whereas Bechdel is very much pulling apart her motives from an adult perspective, Prince’s story almost always sticks with her younger self’s point of view. For instance, Liz notices that heroes are always boys, and girls are always being rescued. When Liz draws a picture at school of her, Luke Skywalker, and her toy Popple, the teacher asks if she’s supposed to be Leia. Liz says, “I’m a JEDI.” After thinking about women who are saved by men–Sleeping Beauty, Snow White, and Repunzel–Liz Prince at age 32 pops in and adds, “So, it’s not that surprising that I would envy those born into boyhood.” Here is an example of the author interrupting her own story:

It happens every so often; adult Liz shows up to add an explanation for or clarification of what child Liz is thinking. It’s almost in the style of Scott McCloud in his pivotal book, Understanding Comics.

Prince analyzes her childhood in a way that will have readers nodding along in recognition. She explains the reasons why children make fun of each other. Again, she inserts her adult self:

“Let’s take a timeout to review some of the reasons you can be made fun of in grade school. 1) Because you’re a girl who dresses like a boy. 2) Because you’re a girl who hangs out with boys. 3) Because you’re a girl. 4) Because you’re a girl who hangs out with girls. So yeah, you can get bullied for ANYTHING.”

A little later, Prince realizes that most of the time, kids are repeating what they hear: “My daddy says you bring lunch from home because you’re poor.” A classmate presents his report: “…and that’s why a vote for George Bush makes the world a better place to live.” Then, little grade school-age Liz says, “We sometimes repeat things we’re told without really knowing what they mean.” In fact, adult comic artist Liz Prince makes her younger self say that, thus proving the point that children repeat.

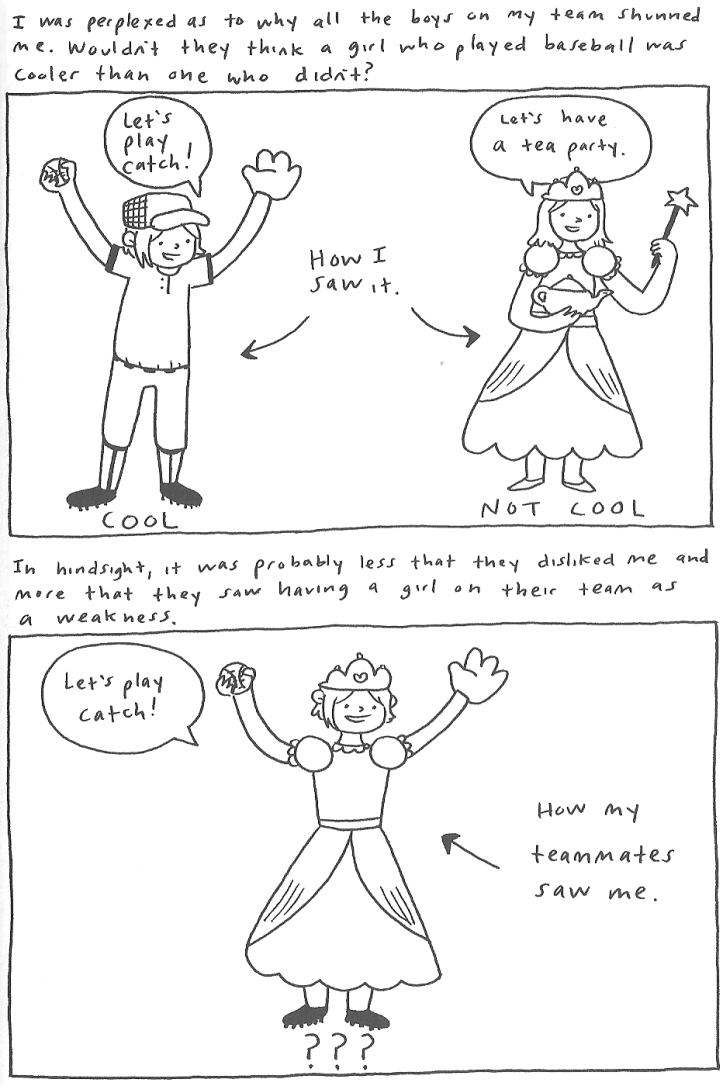

It’s hard to be a tomboy in the world. Girls are told not only how to dress, but assaulted with ideas about how to behave and what gives them value in society. People–both children and adults–reinforce these ideas about gender without question. As a child, Prince buys into gender norms, too, and doesn’t even realize. Boys are cool, so if she looks and acts like a boy, she’s cool. Girls are not cool. But what Prince doesn’t realize is how boys see a girl trying to be a boy:

Tomboy is easy to relate to in a way that made me cringe. I think the camp was the most tragic passage in which many readers will see themselves. At Girl Scout camp, little Liz learns that it’s disgusting to shower naked, swim without a t-shirt, and change her clothes where others can see. The shame is heaped upon girls, perpetuated by other girls, who most likely learned from stupid comments said by parents (who most likely were criticizing other women) and weren’t aware that their children are always listening and impressionable. I remember girls in 7th grade humiliating their friend who got her first period and it leaked on her pants–they kept calling her “bloody butt.” I remember kids in 2nd grade tormenting a girl who picked food out of her teeth and swallowed it–and I was part of the tormenting crowd. We pick out the weak and humiliate them for reasons few of us fully understand.

Playing sports becomes a point of humiliation that readers may recognize, too. Liz plays baseball on the boys’ team for a number of years because it’s her favorite sport. When the coach hands out cups one season, the boys decide Liz needs to wear a chest protector, thus ending her baseball career. Similarly, some girl friends of mine and I tried to play touch football in 7th and 8th grades, but the boys said things like, “Hut, hut, dyke!” and the coach would say nothing. We were run off because we didn’t feel safe from ridicule, even in the presence of an adult.

If you’re about the same age as Liz Prince, you’ll easily relate to the pop culture references she includes. I felt thrown right back into some of the best parts of childhood when she mentioned Nintendo, Sega, Popple, Ghostbusters, and quotes from Wayne’s World. Heck, we even had the same Popple, which I thought was pretty cool and made me like Liz Prince even more. If you’re about 30 years old, you’ll have a good time traveling down nostalgia lane!

One of the biggest ways Liz Prince lets you put yourself into her story and relate to her is through the drawing style. By now, you may have noticed that the pictures are simplistic, basically line drawings without color. In Scott McCloud’s image above, he explains that a very specific image means viewers only picture one person. The more simplistic the face becomes, the more we’re able to insert different people into that one drawing. So, when Liz Prince shows picture of mean girls or boys who are picking on her, they’re vague enough that readers can stick in their own bullies. I immediately remember specific names of kids in grade school whom I hated because Prince’s drawings are not overbearing. The one character you can always easily identify is Prince herself, mostly due to a strange hat she wears in every frame.

If you read this book, you may find yourself experiencing some intense emotions you hoped you’d forgotten upon high school graduation. Yet, the analysis Liz Prince includes will help you think about why children were so cruel, perhaps why you were cruel, and that we all share a universal terrible time in grade school (even the popular kids are hiding something awful). Because Prince wisely makes use of a drawing style and narrative in which people will see themselves, Tomboy is a powerful memoir that will have you turning pages just to see if it gets better–for her, and perhaps even for you.

**Join me Monday, December 14th to read my interview with author Liz Prince! She was gracious enough to take the time to answer my questions about being a comic artist and about Tomboy.

Looking forward to your interview with Prince! It’s a really interesting point McCloud makes about simpler drawings providing an opportunity for readers to project their own experiences onto the text. I hadn’t really thought about that before.

LikeLiked by 1 person

McCloud’s book, Understanding Comics, is a pivotal work, a total must read. I’m excited about Prince’s interview too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks! I’ll look it up.

LikeLike

[…] be sure to check out my review of Tomboy on Grab the […]

LikeLike

[…] Read the full review here! […]

LikeLike

[…] that Ramsey Beyer became a “successful adult.” Liz Prince started in a similar way in Tomboy. Prince’s adult self would jump in the narrative of her childhood to add insights she’s […]

LikeLike